The First Assignment:

It was the summer at the end of my sophomore year when I first got my unpaid internship at The Studio. I was ecstatic, of course. So ecstatic that I was able to overlook the fact that they would tactfully use the term “volunteer” when talking in official capacities of any kind, only allowing me the title of “intern” in casual conversation and on the forums. In order to understand the quirks of my job, you have to first understand the nature of my place of work. The Studio has many projects, mostly dealing with high fantasy or sci-fi, most of which are maintained on a system of weekly releases. This means that, in general, there is always something you should be doing. When The Studio brought me on, I was designated as the assistant writer for their MMO, which is a browser-based fantasy RPG done entirely in Flash. It was 2.5d and played somewhat like a point-and-click, and before I started being able to write weekly releases, I had to add items into the database. As there were always new releases, and thus, new items, data-basing quickly became the only thing I did, day in and day out. It was the closest thing to grunt work that they had for writers, and for the first month or two, that was my life. I would be sent these items and assign them a name and a description. After checking the linkages, I would save the files in the database, and off it went. Another piece of the world that was forever me. And in some small way, I found this work fulfilling. But in a much larger way, the work struck me as tedious and boring. All the same, it taught me something very important. Everything has a story, and those stories must be dependent on each other to form a cohesive and satisfying narrative.

Environmental Storytelling:

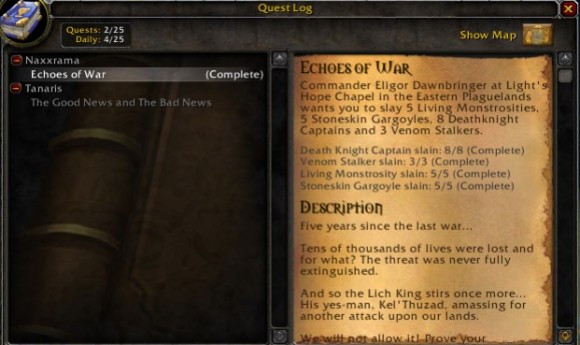

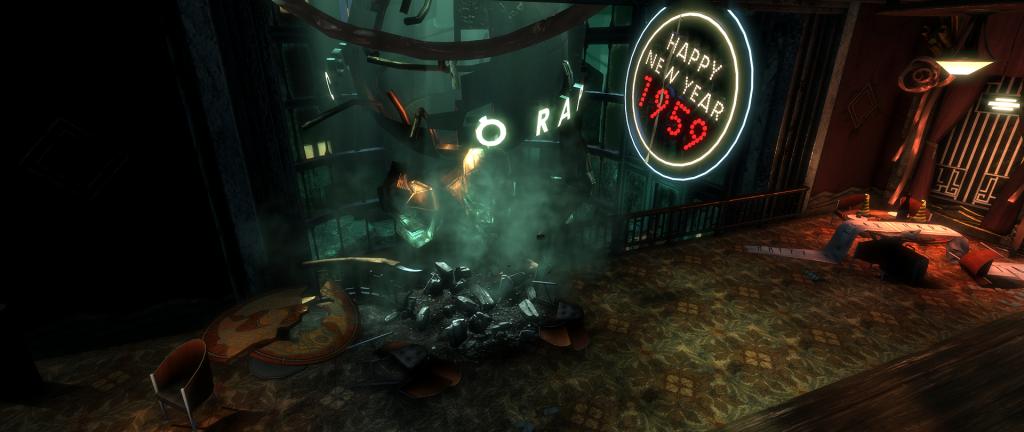

Let’s say you’re in-game on a quest. Along the way, you encounter a bandit with an axe. He drops this axe upon his death allowing you to pick it up. Any writer worth their salt can tell you what the axe looks like, but it is far more immersive to give the item a story based on its context. This context should be firmly established as soon as possible. Where are you right now? It is important that the player answer this question quickly and easily. The axe can be sharp and well maintained, but it takes on a very different persona if you’re in a forest full of felled trees as opposed to, say, a bandit stronghold.

Now that a scene has been set, the next question to deal with is “Why”. Why are you here? This one doesn’t need to be answered quite as resolutely, and in fact, I am of the opinion that self-discovery of the answer can be another satisfying hook into the world. However, it is considered bad form to leave the player with no clues of any kind. It’s alright to drop them into a well-defined world, so long as there are some narrative branches to grab a hold of before they hit the ground. Let’s get back to the quest you’re supposed to be on. Whatever it may be, it should provide the player with some direction, but not enough to be overbearing and stifle the freedom of investigation.

The Aftermath:

At the end of my “internship”, I had gained enough trust for the powers that be at The Studio to write my own release. It was during this process that I learned another important lesson.

No matter how clever you think your story is told, players have no obligation to explore subtlety. This would prove to be a larger problem then I had ever imagined.