Part 1: Activism This Semester

This project in all its forms was a response to the personal ghosts I’ve got living in Hill House, particularly the specter of unaddressed racial and sexual harassment. My first encounter with these reprehensible actions was in my first month at Sarah Lawrence, and I have felt echoes of different situations throughout the years I’ve spent here. No year has left me without this awareness. These toxic actions left their deepest marks when I was a first year living in Hill, engaging every day with the physical space my friends were assaulted in, and being reminded of the institution’s apathy as the horrors accumulated but the space remained the same. These horrors trace their roots to anti-blackness, racism, and misogyny. But they thrive in institutional neglect and the inaction of the larger group. The action of harassment/assault are often committed in public, but in secret nonetheless: in the corners of the hallways, on the fire escapes when nobody’s looking, or late at night when the hallways are empty, and their after-effects are painted over and cleaned up. Like their perpetrators, they hide from view on the edge of plain sight. However, there’s a half-life to unaddressed trauma that causes it to linger in the vision of those impacted. I undertook the project because I wanted to clear my vision, replace it with a public image of resilience and beauty and color.

Fostering that image in my own imagination this semester was difficult. It kept getting interrupted by the realities of life at a predominately white institution (PWI). There is an unhealthy climate around race and racial politics that exists at Sarah Lawrence. On a large scale, this is probably best illustrated by the number of racially motivated bias crimes. This semester there were three so-called “bias incidences” (for what it’s worth, I dislike that formal, sterilized language and the way that it frames the experience). All of them happened in the first month of the semester, the first on the night before classes started. Now, another marker of the health of a community is how well its leadership responds to crisis, and the administrative response to these acts of racialized aggression left a lot to be desired, as it tends to. The first safety alert email contained information on how You, Too, Can Stop Hate Crimes (a list copied and pasted directly from the Orange County Human Relations website). There was a vagueness to the email that left me with many unsettling questions. A group of students calling themselves The Concerned expressed these and many other criticisms in an open letter to the administration. I participated in the preliminary meetings of The Concerned and helped circulate the letter publicly when it was released.

Then, on September 22, Deans Trujillo and Green sent a joint email (“Campus Safety Alert”) informing us about the two separate hate crimes:

This morning, September 22, 2016, the office of Public Safety received two reports involving, or potentially involving, two separate bias-related incidents. The first incident reported involved drawings upon a photo posted on a resident student’s door. These drawings included the addition of cultural and religious symbols, as well as the depiction of an airplane crashing into one of two buildings resembling the World Trade Center towers. In the second report, a student stated his car had been damaged in multiple areas of the vehicle and expressed concern this may be related to race. …

As we respond to specific incidents, we believe it is important to offer support to our community. This evening starting at 5:45 pm to 8 pm, students may join all members in our community in the Slonim Living Room for dialogue and support in this safe environment.

I went to that community dialogue with Deans Green and Trujillo. It was hours long without us coming to many conclusions. The following afternoon, I went to meeting in Common Ground with Natalie Gross, the head of Diversity and Campus Engagement, and other community members. In those meetings, there was a lot of concern about how it would impact the community, but not a lot of discussion about concrete actions being undertaken. I got the impression that the members of the administration who cared had their hands tied by the apathy of the majority who did not. Unless serious action was taken, they would continue to expend the absolute minimum effort in responding to these crises (defining the absolute minimum effort as that which is written in the school’s policies regarding these incidences). I realized it would take serious, organized agitation for them to recognize these crises appropriately. And this level of agitation I was something I was unprepared to offer or organize as a full-time student. It was amazingly demoralizing to realize how little was being done to protect my safety. But there was work being done, I saw, that was desperately trying to address the anti-blackness, xenophobia, and misogyny of these select cowards. I have a deep, abiding respect for those folks who I saw doing the work (who I won’t name because of my relationships in administration). They are students, faculty, staff, and (less senior) administrators who strive to create safety on whatever scale they were able to.

For my own purposes, it’s also important to discuss smaller moments that left me tired and discouraged around my work and the relationship I had with white peers. Sitting outside the library one day, I started a conversation with a couple of casual acquaintances about the presentation of Alice Walker and Yoko Ono in my project (see part 3 for more context). One of them made a number of derogatory and insulting remarks about the two women. One of his remarks was that Alice Walker, who was one of five black students at Sarah Lawrence when she matriculated in 1965, should have “put aside” the racism that she experienced at Sarah Lawrence and continued to be involved post-grad – and then heavily insinuated that failure to do so made her unworthy of the prestigious awards she’s received since. In Yoko Ono’s case – since she dropped out after two years – completing college was not necessary when “you’ve broken up the Beatles.” I distinctly remember a twisting, sick feeling in my stomach as I processed what he said. A white peer dismissing these two women in a textbook misogynist/racist maneuver (the black woman should provide more labor, the Asian woman is only valuable as a sex object for a white man) was disheartening, to say the least. When I tried to push back against his comments, he refused to listen. He literally walked away from the conversation, and his friend just shrugged and changed the topic, effectively ending that conversation.

This moment, however innocuous it may seem to the reader, happened only a week or two after the first bias incident, at a time when I was already feeling unsafe and uncertain of my place on SLC campus because of my racial identity. Now, whenever I see them, I have a gnawing fear of being blindsided again, and I avoid conversation when the opportunity arises. I want to use it to illustrate that Sarah Lawrence, for all its progressive values, is a toxic and damaging environment around race. Obviously, this experience is one small moment in an entire year’s worth of personal interactions I had with white folks at Sarah Lawrence. But neither was it the only damaging thing said or done to me because of my intersecting race and gender identities.

Part 2: The Evolving Shape of the Project

When I started conceptualizing the project in spring 2016, a huge inspiration for me was the work of other Sarah Lawrence students who were working in painting, often specifically murals/public art. My proposal at the time specifically named other artists as the main creators, and my role as the coordinator. However, almost as soon as I got to school, I had a feeling that I had to do the painting myself. This was partially because I was the only person who knew exactly what I was looking for in the mural, and partially because my proposal was only possible if I did one or two murals instead of the proposed six. The project wouldn’t be truly mine unless I put that work in. And so I started the semester with an additional workload, one that I struggled under but eventually came to terms with. Part of my total workload was the stuff I’d already planned – doing discovery meetings with the community, finding appropriate locations, finding paint and painting materials – and part of it was not – researching and realizing a mural for a 12′ x 9′ wall.

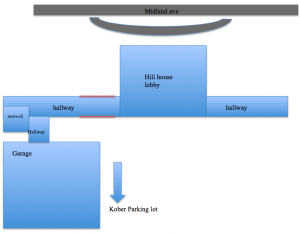

I decided to put my mural in the high-traffic area between the lobby and the back entrance (through the garage). If you look at Image 1, the area where the murals will go is marked by two red lines. When I visited the area with my advisor John O’Connor, we talked about having a sense of motion in the implementation, so there wouldn’t be just a huge wall of color on one side and an empty wall on the either. So I split the length of wall that a one-sided mural would cover – about 12 feet long and 9 feet tall – into three parts, so I had three panels of about 4 feet long and 9 feet tall each. I’m thinking I’ll put two on one side (with a gap of about 4 feet in between them) and one on the other side (with a gap of about 4 feet on either side). This will give a little bit of a visual bounce to area.

I had a walk-through of the area with John O’Connor, as I said, and also with Myra McPhee, the head of residence life, and Mo Gallagher, the head of facilities, together. All three of them gave their okay, although Myra expressed some concerns about finding a good time to do the install, since it would block off the (very narrow) hallway. She suggested doing it during one of the breaks, which is how I decided on Spring Break as my install period (since people will be around, but not so many people that I will be getting in the way).

Part 3: Research on SLC History

Last year, as classwork for Komozi Woodard, I studied the history of student activism within Sarah Lawrence. There were a number of groups who made significant demands and were met with (limited) response by the administration. In 1989, a group calling themselves Concerned Students of Color, made up primarily of black women, organized in response to a racist mural that was painted in Garrison D. In their formal response to the mural, written next to it, they said:

Study this picture. It and the people responsible for it are shining examples of white supremacist attitudes, ignorance, insensitivity, and arrogance. We question the purpose as well as the attitudes of the people who are responsible for, condoned (or took no definitive action against) “work of art.” If the intent of this “work” was to mock racist stereotypes (the big lipped reefer smoking hoodlum n***** and the buck-toothed grinning yellow chink) and the people responsible for it are politicized then why do they place no value in the fact that people of color are offended by it? Our offense makes it a failure in its alleged purpose. Racially sensitive, and politicized people will understand how it is (could not be) offensive. We demand that public art be free of racism. Concerned Students of Color.”

Their protest eventually became an 11-day sit in at Westlands, and their persistent activism established the space Common Ground, gains in the number of PoC professors (unfortunately now gone), and the founding of Dark Phrases, the annual PoC arts publication that I help run. In my research at the archives, I found a number of photographs of the actual sit-in that I’m not posting to the Internet because it would violate my agreement to Archives. However, I will be including them in my personal report to Angela. One of them I plan to use as a reference photo in my mural.

The second group of activists I want to highlight operated under the name Dangers of a Single Narrative Collective, after the Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie essay. They wrote and created a document during the 2013/2014 academic year (my first year at SLC) critiquing the policy of the administration. Their document – an open letter to administration – begins:

We, Dangers of a Single Narrative Collective, are in solidarity with members of the Sarah Lawrence Community who are consistently working for a fuller realization of a safe community. This collective is comprised of students who are concerned about the lack of community engagement with the multiplicities of inequality, exclusion and lack of safe space to speak of race and sexual assault without dismissing and silencing others voices. This collective and the members of the Sarah Lawrence community who support our mission and demands seek to affect tangible and concrete change within the Sarah Lawrence College community.

I was lucky enough to see them speak at Common Ground earlier this semester, after Carolyn Martinez-Class organized a panel for them to speak about their experiences. It cemented something in my mind – that real change is not created in glamorous, flashy moments, but is rather the fruit of a lot of thankless struggle behind closed doors. I knew these women did not get enough recognition or thanks for their work, but hearing them speak about how much open hostility they faced made me determined to honor them for what they’d done for the school and for me (both in terms of the education I received simply from engaging in their work, and in the creation of a safer place for me to do that learning in).

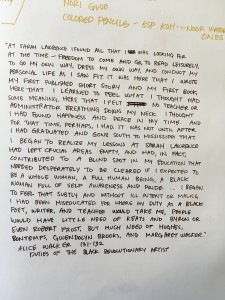

I also researched prominent alumni who were women of color and looked at their time at Sarah Lawrence. While there were a number of people who fit this criteria, two people stood out to me: Alice Walker and Yoko Ono. Their continued successes have inspired me at my lowest moments: when I’ve felt my work was unimportant or I saw a world that was too white to fit me. I was able to find visual material of their time as Sarah Lawrence students, which I put below. In Alice Walker’s case, I also found two essays she originally gave as speeches at Sarah Lawrence, which I’ll quote below:

But please remember, especially in these times of groupthink and the right-on chorus, that no person is your friend (or kin) who demands your silence, or denies your right to grow and be perceived as fully blossomed as you were intended. Or who belittles in any fashion the gifts you labor so to bring into the world. That is why historians are generally enemies of women, certainly of blacks, and so are, all too often, the very people we must sit under in order to learn. Ignorance, arrogance, and racism have bloomed as Superior Knowledge in all too many universities.

I am discouraged when a faculty member at Sarah Lawrence says there is not enough literature by black women and men to make a full year’s course. Or that the quantity of genuine black literature is too meager to warrant a full year’s investigation. This is incredible. I am disturbed when Eldridge Cleaver is considered the successor to Ralph Ellison, on campuses like this one – this is like saying Kate Millet’s book Sexual Politics makes her the new Jane Austen. It is shocking to hear that the only black woman writer white and black acaemicians have heard of is Gwendolyn Brooks.

Fortunately, what Sarah Lawrence teaches is a lesson called “How to Be Shocked and Dismayed but Not Lie Down and Die,” and those of you who have learned this lesson will never regret it, because there will be ample time and opportunity to use it. (from “A Talk: Convocation 1972.” Ironically, I first heard this read in my African American Literature course this semester).

Part 4: Art and Influences

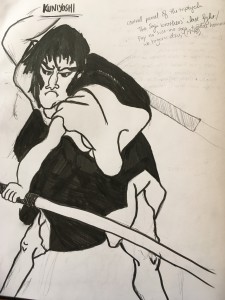

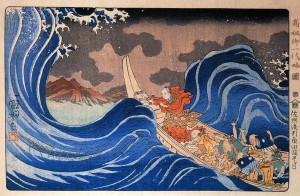

I paid a lot of attention to public, popular art in looking at references for my mural. I spent a lot of time with the Japanese woodblock artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi, because he made flat spaces dynamic just through his line work and the way he posed the figures of his prints. I also really enjoyed his color balances, although I wouldn’t necessarily take inspiration from them.

I also went to see Os Gemeos’s show at Lehmann Maupin gallery, called “The Silence of the Music.” I knew of their work from the midnight moment they did in Times Square, but this was the first time that I got to interact with it. I was super, super inspired by the way they transformed the gallery space – typically something super white and sterilized – into a visually dynamic, playful area. It’s kind of similar to the visual dynamic of anime, where it’s very colorful and pinwheeling and dancing. What Os Gemeos did at Lehmann Maupin is the exact dynamic that I want to bring to Hill House – both the original white sterility and the visual playfulness. Os Gemeos started their work in street art, and actually only began a studio practice under Barry McGee’s advice, and I think that’s part of why they drew me in so much. I was looking for something with the visual dynamic of a really good piece of graffiti or an irresistible billboard, where you can’t help but look at it, and then you can’t stop staring once it’s there. Like it’s become a part of the landscape. I think that’s a characteristic in the work of people known for their stuff in the street – even if it’s not in New York galleries, just people whose work is easily recognizable from traveling around one city a bunch. (I’m thinking of GATS and RasTerms in Oakland as well, although that whole PTV crew could easily fit under that category as well. GATS and Ras just cover the most ground.)

My third visual reference/inspiration was Jack Mitchell’s photographs of Alvin Ailey dancers. I have always, always, always loved good dance photographs, because they fill the space in these impossibly graceful but super realistic, truthful ways.

I got super fascinated by the motion and shape of the body. It actually inspired me to include a dancer in my final thesis. Seeing the bodies of dancers in exuberant motion is like a visualization of joy.

Part 5: Concept Work and Moving Forward

I have some very, very rough drafts of my concept art. At this point, I have mostly collected reference photographs and composed them on my big pages. But the rest of this break is going to be devoted to turning them into complete pieces that I can bring to my discovery meetings. And I will be showing them to my advisors during registration week of Spring semester.

Once I have them completed, I’ll be scanning them (unless I do them on a tablet) and projecting them onto big sheets of paper, then tracing them with a heavy graphite pencil so that I can transfer the pencil marks onto the wall before the basic, collaborative paint install.