For many, many weeks, the only question people would ask me was: “so, how’s the cocoon?”

Admittedly, because of this, the cocoon felt successful before I had even installed it: people were talking about it, and that is the first step to public art.

This all began in a class as we discussed Heimbold, the visual arts building at Sarah Lawrence College. Heimbold has three intensely obvious characteristics: it is built with steel, concrete, and glass; the space is large and intimidating, with little emotional or physical access to the building itself; and, much like its typical occupants, Heimbold is suffocatingly white.

We framed Heimbold as a problem to solve. How do we work with and against the building itself to create successful, affective art? One student commented that “your eyes are welcome, but your body is not.” This comment is what created the cocoon.

Initially, the cocoon was a hug machine. Taken from another project series, the Hug Machine extends from the walls of the building it is installed in, and envelops the participant in a comforting, human-like hug. However, there was something incomplete about the Hug Machine. Andrew Boyd, editor of Beautiful Trouble (a text I read towards the end of my time with the cocoon), writes quite smartly in his manual to good art: “praxis makes perfect” (Boyd, 162). After trying to digitally construct The Hug Machine, it became clear that certain elements were more important to me than others; the softness, enclosure, and positive intent of the Hug Machine were what really appealed to me.

At a loss and needing a project, I reviewed some of the texts from the semester. I spent 90 minutes in a bubble bath rereading Edward Bernays’ Propaganda, a 1928 classic on the nature of Public Affairs, business, and the public. In Propaganda, Bernays gives several stories of companies working with the public in a sleight of hand; they would promote their projects through public works, contests, and academic studies. (Bernays, 70-79). He explains why this is justified:

“The development of public opinion for a cause or line of socially constructive action may very often be the result of a desire on the part of the propagandist to meet successfully his own problem which the socially constructive cause would further. And by doing so he is actually fulfilling a social purpose in the broadest sense.” (Bernays, 73-74)

Bernays’ idea of social uplift or change happening in conjunction with and for the intent of business made me think. Earlier, we also studied Nikeplatz, a piece by Mattes & Mattes.

Nikeplatz was created as a reaction to people placing company logos, and therefore brand identities, both on their body through clothes and in their spaces through advertising. However, the piece itself was simply a performance of Mattes & Mattes unveiling a building-sized sculpture of the Nike logo in a public park and interviewing passing people about it. This proved much more effective than a simple statement like “corporate logos are bad” or “where are you putting brands?” Because Mattes & Mattes’ piece was not necessarily the construction itself but rather the reactions, people felt that their opinion was their own, and in natural reaction to the over-the-top commodity occupation. Much like Bernays suggests, the most potent propaganda isn’t direct, but conscious of how to influence social dynamic. I desperately wanted to join in on the fun.

The Hug Machine’s redesign involved three necessary components: soft materials, a feeling of enclosure, and an enforced distance between participants and Heimbold itself. My mission was to redevelop Heimbold as a space, sneakily, so that people would feel both welcomed and comforted in a typically hostile space. The combination of these key elements are what lead me to the cocoon. Cocoons wrapped their occupants in soft, shapely domes that were produced naturally in high-bug/butterfly/worm areas. The metaphor of nature invading a deeply removed and unnatural space excited me, as did the easy recognition of the material and shape. It was going to be wonderful.

For the cocoon, I studied many naturally occurring cocoons. The shape that appealed to me most (and seemed most iconic) was the shape of a moth’s cocoon; the silkworm’s cocoon had a texture that fit my ideal balance of softness and ephemeral weightlessness; finally, in considering how humans should interact with it, I referenced Nacho Carbonell’s Cocoon Seats, an installation that allows people to interact from the shoulders down with their heads in a cocoon. Although I wanted a singular experience for the cocoon, the way that Carbonell creates a simultaneously singular and social experience greatly appealed to me.

After a consultation with our fearless art leader, Angela Ferraiolo, I began experimenting with fabric. This featured a bucket of cornstarch, several fabric samples from the internet, and a tiny knife. My process was testing each fabric (felt, cotton, wool, and raw cotton) for two things: rigidity and fluffiness. I distressed each fabric by sliding the small knife into the surface layers of the fabric and pulling up small tufts; this proved most successful for felt and the raw cotton. However, the second test for rigidity eliminated the felt, as a few days after applying the cornstarch, the felt molded. In sight of my research, I ordered six feet of raw cotton batting for my cocoon.

This is where the real construction began. I spent several days cutting the sheets of batting into two panels, designed so that when they hung together, they would look like the moth’s cocoon. To support and set this style, I also sewed in over 25 ft of copper wire so that the cocoon could bend in odd shapes and styles, but maintain its overall shape. There were two wire inserts other than the outline of the cocoon, which gave the piece its sense of depth and movement.

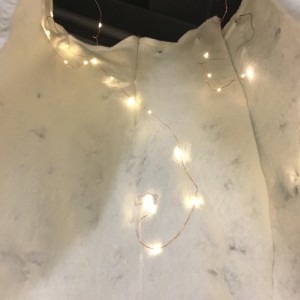

The final step, and my personal favorite, was the lights. To reinforce the ephemeral feeling of the light, fluffy distressed cotton, I sewed in four LED copper string lights, creating spirals and curves along the inside of the piece that later wove up the copper supports that held it in place. The lights were beautiful, and glowed just enough that they were visible from the inside but somewhat hidden from the outer world, helping to divide the conceptual cocoon space from the real world Heimbold Space.

The installation itself both succeeded and failed, in my opinion. When hanging the actual cocoon, I ran out of the copper wire that I used to suspend it from the supports of the second floor staircase. Although tragic and frustrating at the time, I nudged, angled, and twisted the wire until it came to a satisfactory, semi-closed shape. The final touch was two small stitches that closed the cocoon from the back and a single red chair underneath, to encourage people to not only interact with the piece, but do so leisurely.

There are several things I wanted to do differently in this piece, but I consider them lessons for future projects. My biggest regret is, like the cautionary tale that Seres Lu tackles in Graffiti vs. Street Art, my piece was art. There was something inherently limiting and classist about my piece being art, which was counter to the intent of an equalizing, sheltering space. Still, in my many trips through Heimbold, I caught several people resting in that red chair and staring up at the lights that twinkled around them.

As an artist, I see many conceptual and aesthetic flaws in my piece (namely, the uneven hand stitches that secured the wire within the piece and oddly bourgeois nature of art)— as a student, I thought that the cocoon was a perfect respite.

![Cultural HiJack: [Scholar’s Library]](https://astoryisnotatree.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/twitter-bg.gif)