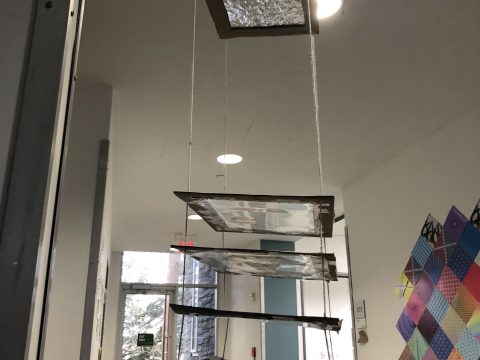

For my conference project, I wanted to explore the themes of paranoia, cult, and narcissism, all informed by Sarah Lawrence unique population, philosophy, location, and history of cult-like behavior. The uncanniness of these aspects of the campus sent me towards religious cults and how they are constructed. I began to explore Arnold Schoenberg’s unfinished opera, Moses und Aron, and found the dramatic structure and musical choices incredibly moving. The painful relationship between Moses, who defends an unseen unknownable God, and Aron, who provides his people with Exodus and glory, drew me into questions of masculinity and, relating back to Sarah Lawrence, the “golden dick” phenomenon. I decided I wanted to film the narrative of the opera as if it occurred on campus. This film, I knew, would depend on how compelling the two title characters could be, despite their maniacal, paranoiac, and occasionally perverted actions. Thus I decided to frame the film with in-person performances. At the start of the piece, Moses expresses both guilt and disgust for his current imprisonment to institutions, eventually awakening a burning-bush-voice which announces Aron’s and Moses’s impossible duties.

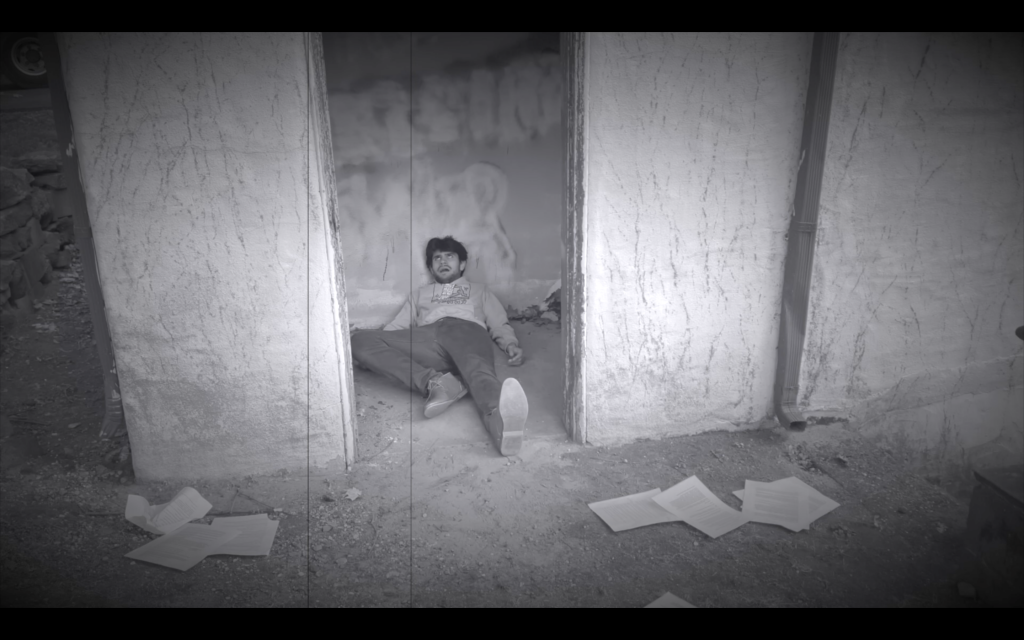

If Moses is paralyzed by the impossible request, then Aron dives headfirst into action. Walking behind the monitor, he is drawn towards an intimate graffiti-filled extra room of a dorm. Thus starts the filmic section; Aron controls the screen space as Moses watches hopelessly, eventually opting to type his prophetic rants while turned away from Aron’s screen. I saw Aron as a figure of melodrama, so I decided to emulate Fritz Lang’s “Die Nibelungen” and “M.” The silent film style reflected the archetypal, atemporal visions of both Moses and Aron, although Moses’s gaze added a creepiness which was not intended by Aron. Yet, as Aron initiates his campus friends, he is able to ground Moses (or at least his image) within the screen. This is his miracle, and it inspires the exodus and faithfulness of the people.

As the narrative gathered steam, I realized I could utilize my theatrical friends and peculiar dorm room as part of an assemblage to bring new life to the familiar golden-calf/orgy scene in the Bible and Schoenberg’s opera. Aron arouses this colorful episode by performing the ultimate “evil” act: creating words and idols without Moses’s guidance. Having revealed his Holy of Holies as a space next to God, Aron gifts this closeness to the cult members. This is the heart of my theoretical statement, that once the central negative hole of paranoia has been filled with a positive object, the cult is out of the hands of the leader. Thus, the cult begins to function on its own, creating its own rituals and exploring bodily pleasures as a group.

The orgy scene is informed more than any other by its scoring. I landed upon Patti Smith’s cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Because the Night.” I felt that the melodramatic and expansive 80s sound, blended with the erotically self-destructive lyrics, had enough formal similarities to the piano music of Arnold Schoenberg (which I used for Aron-led scenes) while still expressing the takeover of the narrative by the cult. Once I located Bruce Springsteen as a valuable artistic influence, I began to associate Aron with Tom Waits, who I view as distilling and exaggerating the compelling aspects of Springsteen in his work. All the musical pieces for the film, including the two Tom Waits songs, were centered around or started with the piano, the instrument traditionally used to score silent film.

The ending of the piece was incredibly important in pulling together the mixed media aspects and tonal shifts. As Aron wanders away from the ruins of the orgy, he approaches the room, where Moses awaits him, and synchronously returns to the framing performance space, reaching for Moses in the monitor. Thus, despite seeing the direct consequences of Aron’s choices, I hoped the audience would relate to his commitment to ethical behavior beyond Moses’s obsessive neuroticism. In the end, Aron has turned Moses into the figure he needed to be, and the audience is implicated in the cult’s endurance.