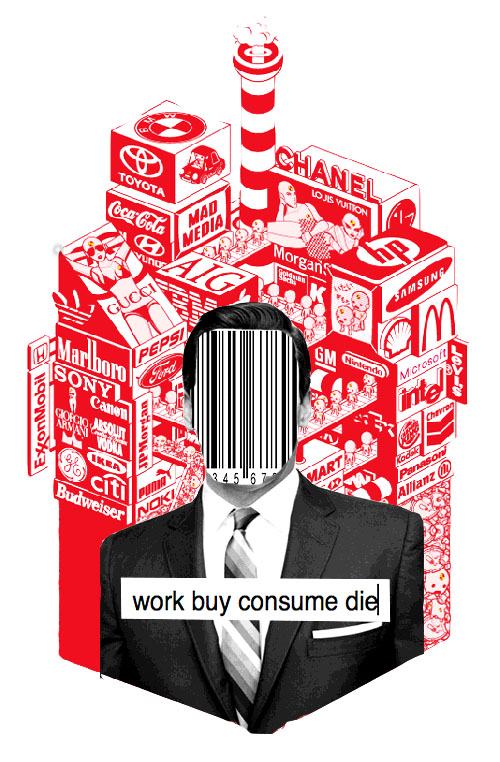

American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer has created revolutionary urban installations that have been exhibited throughout the world, with a strong focus on visual displays of text in public spaces. Holzer is particularly relevant to the study of urban installations and public art, and has contributed to the ongoing quest to bridge the gap between the public and the private that is inherent to cities. The latest volume of the Urban Screens Reader, edited by Scott McQuire, Meredith Martin and Sabine Niederer, presents a collection of remarkable essays that strive to explore and challenge the nature of urban screens in modern cities. The first part of the reader offers a historical exploration of public media displays and urban screens. In his essay “Messages on the Wall: An Archeology of Public Media Displays”, Erkki Huhtamo discusses commercial billboards: “It really was a huge emblem supposed to imprint an idea – the trademark – into the minds of the passers-by.” (p. 21), and through her subversive artwork, Holzer seeks to counter the capitalist usage of billboards and broaden its social, political and cultural possibilities. By embedding her work in the urban landscape, Holzer transforms her art into a lived and shared experience. Through language, Holzer provokes city dwellers and invites them to be active participants of the city experience, rather than simple spectators of society as Guy Debord would put it. Holzer is best known for her “Truisms”, her statements that are somewhat self-evident, that she projects onto billboards, LED screens, buildings or historical monuments, through the most minimal, raw medium of text.

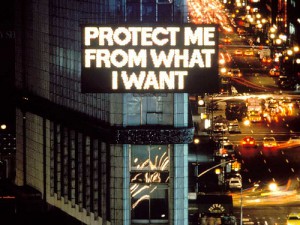

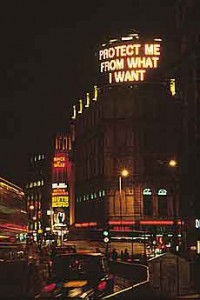

Holzer first projected her “Protect Me From What I Want” piece in 1986 as part of her “Survival” series (compiled in 1983-1985). The piece was installed on an elevated billboard in Times Square in New York City, and the text is lit up by LEDs. The projection addresses, in an ironic yet authoritative manner, the power of consumerism and the frenzy it entails. Through this short and simple statement, Holzer acknowledges the overindulgence and excess inherent to modern society and capitalism. By projecting it onto a billboard in Times Square, Holzer directly challenges this society of consumption and spectacle that we live in. What is so fascinating about this piece is that Holzer succeeds in transforming a self-evident statement into a subversive work of art, by embedding it precisely in the representational emblem of capitalism that is Times Square. The success of this piece lies in Holzer’s achievement to both mock the global consumer as well as herself, through the most suggestive representative display of the advertising billboard. The form and content of the piece also represent a duality that is essential to the piece. The statement “Protect me from what I want” suggests society’s desire for excess, yet the form of the piece could not be more simple. These two elements complement each other and are what make this piece so great: the visual form informs the meaning of its content and vice-versa.

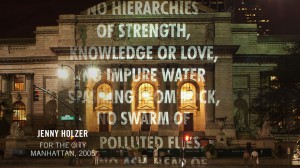

Her project “For the City” (2005) is a series of light projections of selected poems by Wisława Szymborska, Yehuda Amichai, Henri Cole, Mahmoud Darwish, and other celebrated writers. The light installations were projected onto the Rockefeller Center and the New York Public Library. The poems were projected in motion, just like credits rolling at the end of a film, engaging city dwellers to interact with the piece by reading the poems as they moved. In this piece, Holzer displays the power of language through its highest form, poetry, using poems that speak of emotions of hope and pain. Simultaneously, Holzer projected recently declassified U.S. government documents onto the Bobst Library of New York University. By projecting these documents, Holzer speaks to the thin line that separates secrecy and transparency, as well as private and public. The texts projected were selected from the Freedom of Information Act passed in 1966, so here again, Holzer expresses a duality through the form and content of the piece. The name of the act, Freedom of Information, suggests the free access to information, and so, by literally projecting the act onto a public building in a public space, Holzer merges form and content in a way that is particularly subversive yet feels so evident. All of the light projections that constitute this series express ephemerality as the words scroll down the buildings, succeeding each other and then disappearing. Every city dweller that passes by these installations shares a similar experience, but may witness different phrases being projected. In that sense, the project really addresses the relation between private and public, through its content but also through the concept of individual versus collective experience. The project is public, yet one’s experience is unique and individual.

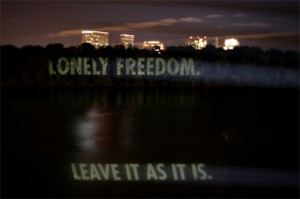

Her project “For the Capitol” (2007) takes a similar form as “For the City”, composed of light projections of texts. The installation was composed of a series of quotes projected from the John F. Kennedy Center across the Potomac onto the greenery of Roosevelt Island in Washington D.C.. The selected quotes are from the two presidents, John F. Kennedy and Theodore Roosevelt, and scrolled down the greenery onto the water like film credits, just as in “For the City”. The quotes speak to ideas of peace, war, patriotism, the environment, governmental power, the responsibilities of a president, people’s responsibilities as citizens, and the role of artists in modern society. The ephemerality of the piece engaged the public to participate in it by actively reading the quotes, that strived to engender reactions. In this sense, Holzer’s piece aligns with Bourriaud’s view that Liliana Bounegru speaks of in her essay “Interactive Media Artworks for Public Space: The Potential of Art to Influence Consciousness and Behaviour in Relation to Public Spaces”: “Art, therefore, becomes in Bourriaud’s view an urban experiment, no longer something to be looked at, but something to be lived.” (p. 206) The ephemerality of Holzer’s piece is in that regard of essential importance as it suggests the experimental and social quality of the piece. The projection of the piece was not rehearsed or static, and was very much contingent on the presence and participation of the public.