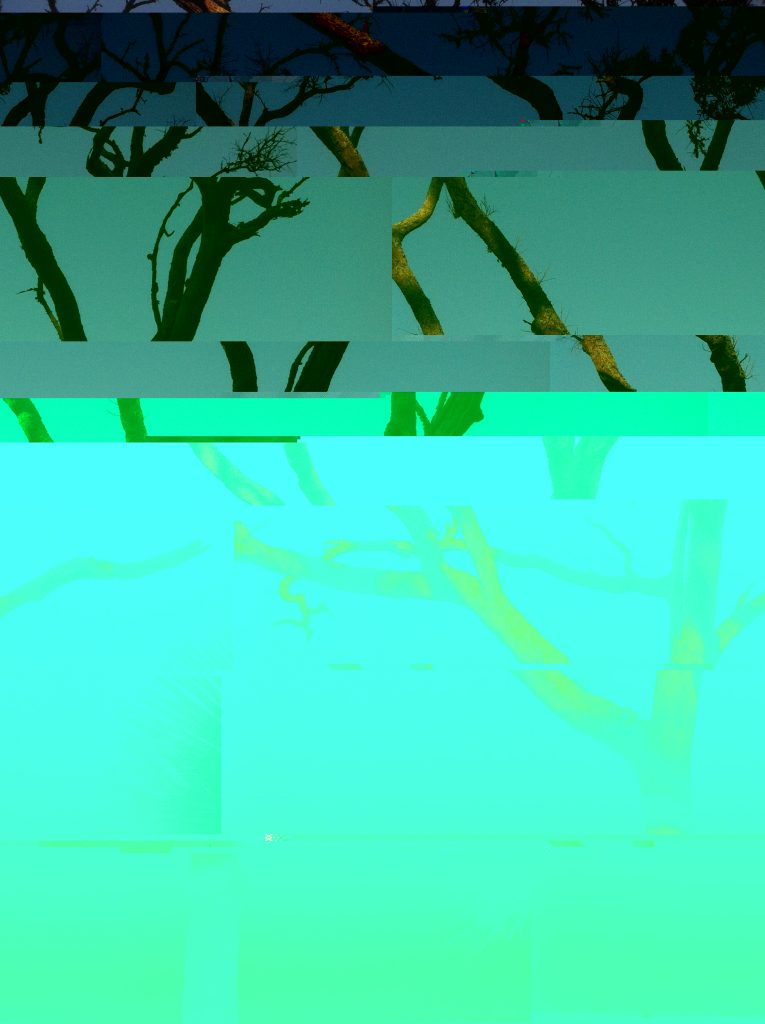

Based on the amount of control an artist gives up in attempting to glitch an image paired with the end-result of a computer producing a nonetheless beautiful product, it gives weight in my mind that there is an art of machines. In a vague sense I knew that some machines were capable of drawing, but that I could create art by giving a computer a set of random or contradictory commands and it would spit out more and more interesting and often abstract works broadened my appreciation to what was possible. I would classify my glitches as an easing into the mindset of following where my hands and eyes went. I began to just do, and if I didn’t like it, I would do it again. And again… and again… and again.

Giving up control to a computer felt somewhat natural. To spew buffoonery onto a page of code and let technology do the heavy-lifting to interpret it is just symptomatic of being a college student living in the modern age. Yet, to also know some of the ins-and-outs of why the computer was interpreting different corruptions in a certain way intrigued me enough that the back and forth, interference and response, made it feel like I was having a conversation with the computer. It wouldn’t always spit out a response that I liked – and I found I liked more color, small details, and large disruptions – but I found I appreciated any difference in the original image because working inside that image made me feel connected to it. Mallika Roy says in “Glitch It Good” that “[g]litch art starts conversations that traditional art forms can’t really access”. I agree, my original photos have gained a new meaning in the way that they have been abstracted and “ruined” – ruined in a way that some familiar elements and memories remain where others have been completely lost.

If glitching awoke my interest in small details and large swathes of color, scanning ignited it. With the help of high resolution scanning and the added control of being able to tune and preview the final product, emphasizing areas that interested me in an image became the focus of these projects rather than merely findly new and interesting ways to twist a picture.

I started a little reserved, making scanning collages that were meticulously planned and didn’t include a lot of disturbance in the way of a glitching-influence. It was all very tame. But as I got tired of doing the collages, discontent with how they panned out, I turned to looking into one tiny aspect that did spark my curiosity: texture. I admit, textures, striations, and aberrations in otherwise perfectly smooth objects was on my mind since I’d noticed my jacket was fraying a bit. This little nuisance gave me the urge to study the many different textures of one object. From there, I began to think about what other things would highlight very fine details and finally came upon my study of lace and embroidery. Those elements, mixed with the shadows that the scanner translated as dark trenches and the brightness of the threads – maximized by playing with the contrast of the image – allowed me to create the following scan.

And I say “allow” because although scan art grants the artist varying degrees of control – the ability to hold, arrange, and create items placed on the scanner and the ability to manipulate the settings on color and resolution of the final image – the art is nevertheless still seen from the perspective of the scanner and is therefore removed from a person’s demand for control. I cannot control precisely how the scanner will interpret an array of items stacked on top of each other, even if I can control that they are exactly 1.5 inches apart. In fact, when I displayed too much control, as I did originally, the art became less interesting and if not boring, plain to look at.

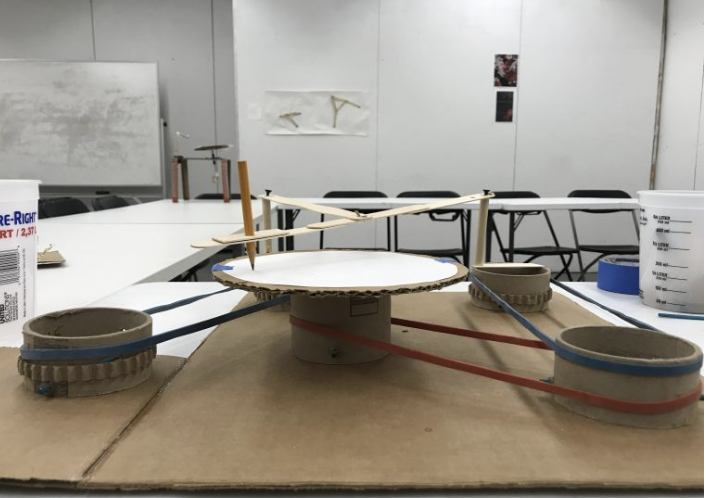

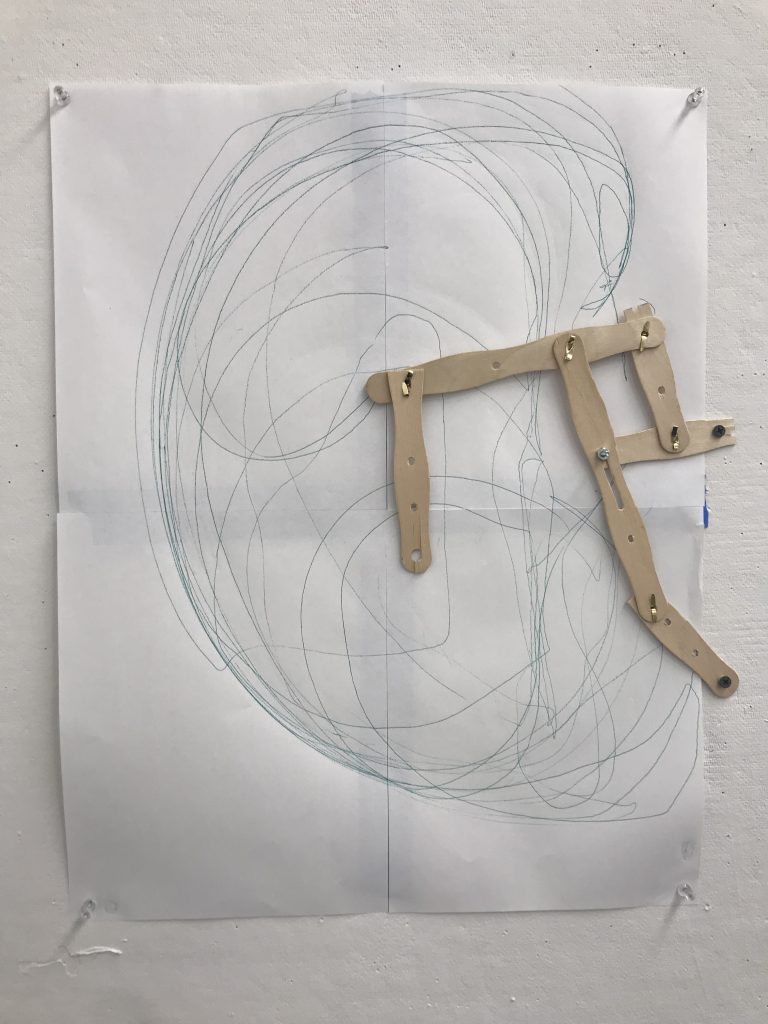

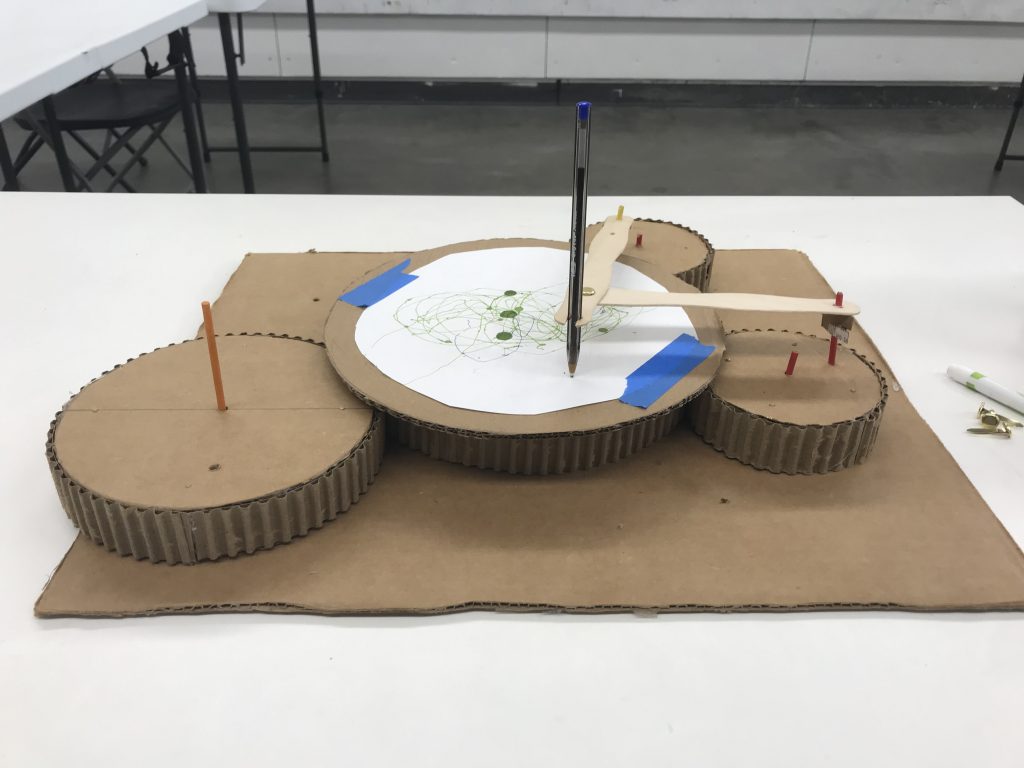

When it comes to experiments in analog, I felt a little more disconnected – uncomfortable with my inexperience – than I did with a machine like the computer or scanner. It felt like I had too much control and therefore I would often have to fight my need to make something precise. Over time thought, as the frustrating fruitlessness of that mindframe set in, I began to fall into the technique of following my gut to make something with no real solid plan other than having a few elements that I thought would work and a desire to create something that looked nice and worked in a smooth, interesting way. From there, I would adjust the product as needed. A lot of analog-heavy projects also pushed me to do more research and watch a few videos for more inspiration of different machines and methods to use.

It was in this environment that I really felt and saw a shift as I went with the flow of mistakes rather than trying to force elements like gears or tongue-compressors with nonsensical sliding patterns into what I thought they should be before even seeing them in action. It’s a work in progress.