It was immediately clear to me the day I got my hands on an entry level Epson flatbed scanner that it was going to present a sort of new working method in which I was very interested.

You immediately understood that the flatbed scanner is a kind of digital camera, but one that recorded surface details in a way that is different from a traditional digital camera. They record surface details in an entirely different manner. In a really simplified sense, a traditional camera utilizes a lens to compress a three-dimensional space into a two-dimensional surface which is then recorded, all at once (sometimes technically not instantaneously), by a rectangular array of digital sensor cells or photosensitive chemical. A flatbed scanner, on the other hand, is essentially designed to only deal with two-dimensional surfaces. Without a lens, a flatbed scanner replicates a two-dimensional surface, for example a piece of document or a photographic print, that is in physical contact with the scanner surface.

The first experiment I did in treating the flatbed scanner as a kind of photographic camera is to use the scanner to make portraits of people by having them press their face right up against the scanner glass. This created an incredibly dream-like affect, as only the part of the face that is pressed perfectly against the glass is sharply and correctly resolved. The rest of the face becomes entirely blurry, and the environment is rendered simply as shades of light gray or white.

In someways, the extremely shallow depth of field evoke a surreal quality similar to portraits made with 8×10 cameras at wide apertures. A simultaneous feeling of intimacy and distance is generated in these pictures. The viewers can feel the “pressed-up-against”-ness of the pictures as if they are literally touching the surface of the person. At the same time, the invisible scanner glass is also materialized in this mode of portraiture: we cannot reach through the glass to get to the person in the picture.

After these portrait experiments, I started to think about other ways I can use the flatbed scanner as a camera. Having had some previous experiences with large format view cameras, I saw the flatbed scanner as potentially a kind of “digital back” for 8×10 view cameras. In this usage, the scanner is essentially given an extra dimension. With the view camera and the lens, the scanner is now concerned with a three-dimensional space and no longer a two-dimensional surface.

However, in order for the scanner to see three-dimensional space, I realized that I need to give the scanner a flat image and not a light projection from a lens. In order for an image to be formed prior to being captured (scanned), I taped a piece of ground glass, used for composing and focusing the view camera, onto the scanner. Then, I taped the scanner/ground glass assembly to the back of an 8×10 view camera.

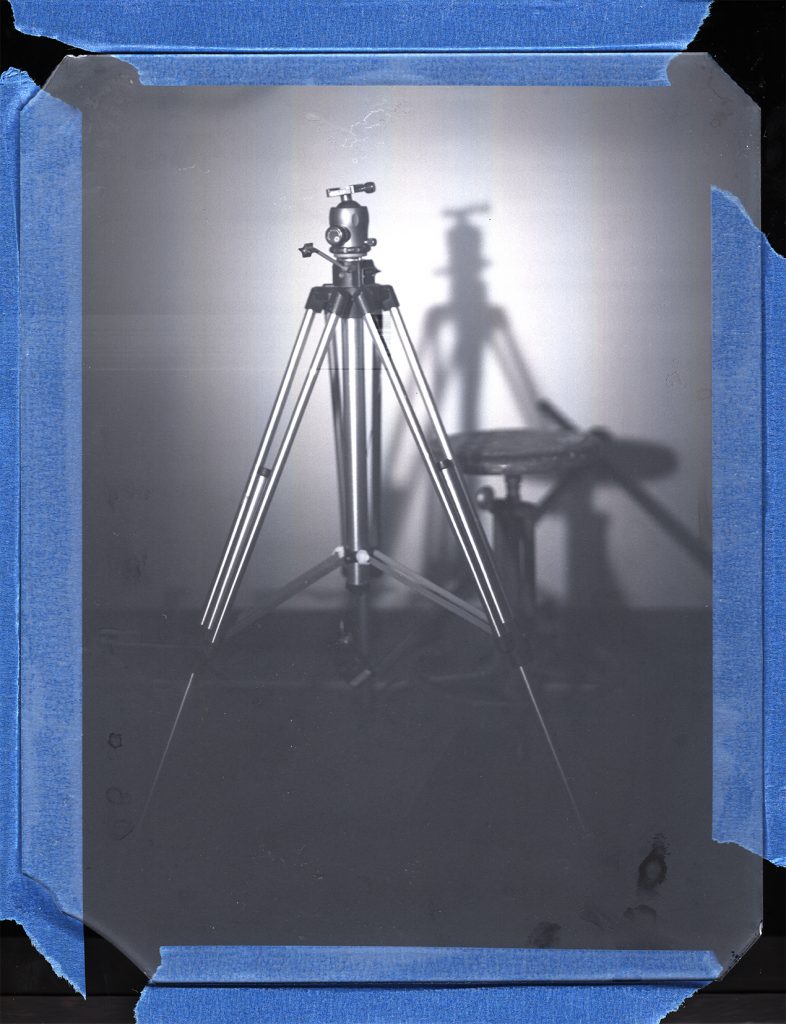

This assemblage required a lot of light to function, and since the image is scanned instead of made all at once, the light had to be continuous. I flooded the photo studio with lights, and for my first attempt with this scanner view camera, I photographed a tripod that was readily available in the studio:

This is one of those images that, the more you spend time with it, the weirder it gets. You can see the blue masking tape used to hold the ground glass in place, the edges of the ground glass, and the projected image on top of the ground glass. This is less of a photograph than a photographic description of what a photograph is, and I realized that the kind of meta or self-referential quality that this image possessed was going to be the key point of interest in this project.

Despite this project’s ability to be a kind of self-referential reflection on the mechanism of photography itself, I was also looking into interesting ways that this system dealt with space and time. One of the more exciting photographs made during these experimentations is this photograph of a road and some trees:

This is captured directly by the scanner with only the contrast and brightness adjusted after the fact. On the road, you can see strange vertical lines, and it is not until you zoom in and look very closely that you realize that those are cars that was moving counter to the direction the scanner was scanning. As a result, they became horizontal compressed to almost a single line. This temporal distortion was extremely striking to me. As I mentioned earlier in the post, most modern cameras don’t technically record the entire image at once. Rather, the camera reads the sensor readout from top to bottom, line by line, extremely rapidly. This time differential is rarely identifiable in photographs because the reading of the sensor happens in the increments of thousands of seconds, but if you look at fast moving objects such as race cars or airplane propellors, you can observe the strange artifact generated by the “rolling shutter effect.”

With the scanner camera, because the speed of the scanning head is so slow, essentially anything that moves is heavily distorted temporally. As a result, it creates an interesting relationship between things that move and things that stay still, or, in other words, almost always, the inhabitants of any environment, and the environment itself.

This is all my exploration with the scanner camera so far.

–Yuan Oliver Jin