My experience with “finding a form” began with a misunderstanding of the prompt. Originally, I had thought “Collect Evidence” was a call to make a work of conceptual art using the idea of evidence, rather than just compiling loose photos and objects like we were supposed to do. In doing this, I came to realize very quickly the difficulty for me with this assignment: when I make conceptual art, the form is married to the concept from the get-go, and thus separating the art into evidence and forms for me is super counterintuitive. This difficulty would persist throughout my experience with “finding a form,” resulting in a series of works that, while all revolving around the same central universe, feel very different to me.

Form 0. A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE CHEERS UNIVERSE

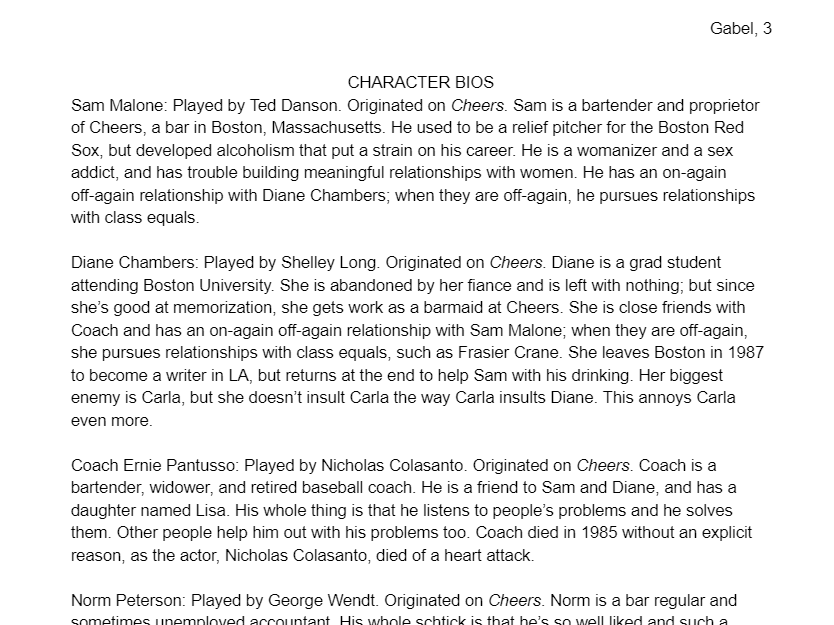

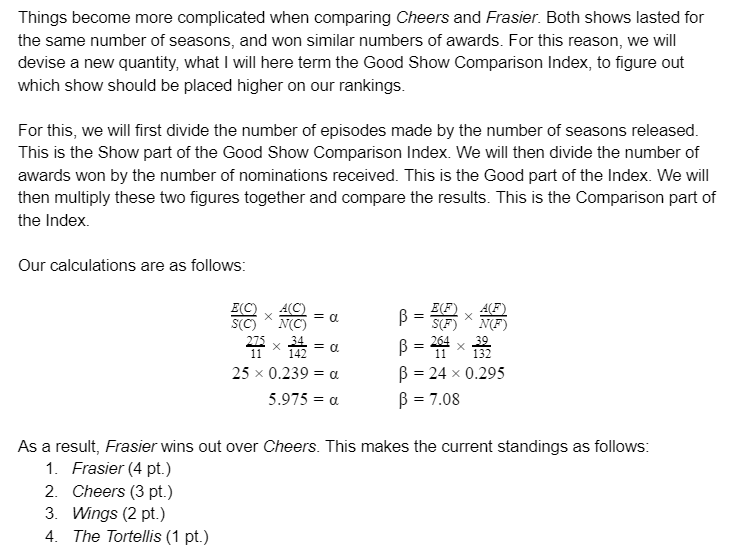

This project began with a simple question: What if I, Emma Gabel, someone who has not seen a single episode of Cheers, and only a little bit of Frasier, became the foremost expert on the Cheers expanded universe. I started by devouring the Wikipedia pages for Cheers and its associated shows, Frasier, The Tortellis, and Wings. I learned all about who made these shows, when they were made, and how they were received; I learned about all the different characters, their relationships to one another, their conflicts and their developments; and I learned about what made these shows tick, that being a fundamental awareness of class divides in America. I then proceeded to break these shows down, comparing them to one another, and grading them in three areas: Longevity/Awards, The Character Simplicity-Character Depth (CharSimp-CharDep) Balance, and the Class Consciousness (CC) Scale. In doing this, I was able to determine, without having really watched any of these shows, that Cheers was the best, followed by Frasier, Wings, and The Tortellis, in that order. I then presented this evidence in the form of an academic paper, because that was what made sense for this evidence; the concept revolved around taking this series of primetime TV sitcoms and subjecting it to a scientific analysis. To me, then, the project was complete, as the concept had already found its form.

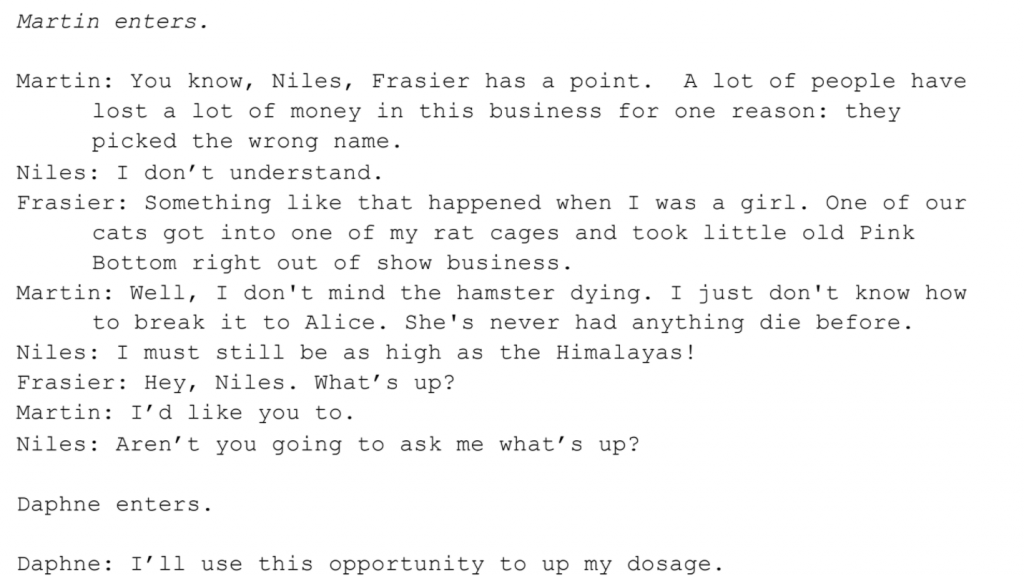

Form 1. NILES [Spec Script]

When tasked with creating a new (“first”) form for my evidence, I encountered a lot of difficulty. I had already taken my evidence (31 seasons of primetime television), made associations with it, and placed it in a set syntax. And now, I had to go back to square one, untangle the associations I had already made, and find a new syntax. What I ended up with was a script for a performance art piece, composed entirely of lines of dialogue from episodes of Frasier, under the pretense that it was a spec script for a Frasier spin-off entitled Niles. Originally, I had wanted to use my research of the Cheers universe to make this essentially the perfect episode of a Cheers-universe show: it would have a good CharSimp-CharDep Balance, score high on the CC Scale, and go on for many seasons and win many awards.

However, this quickly proved to be impossible, since reconstructing a coherent episode of television from 264 episodes of Frasier, Frankenstein’s Monster style, is incredibly difficult. As a result, I decided to make the piece incoherent, an absurdist descent into the psyche of Niles Crane once he, like myself, is made aware of the Cheers extended universe. It was here that I began to run into another issue, one that would plague this project until my final form: most folks in this class have not seen Frasier, and thus don’t have any context for a performance art spin-off episode. I had tried in the script to play with my associations with Frasier, and with the syntax of a primetime TV sitcom, but neither of these subversions came through in the piece. I was now operating, not as a total newcomer to the Cheers universe, but as the expert I had sought to become, and thus my work did not make any sense to anyone.

Form 2. A NORMAL EPISODE OF FRASIER

I tried in my second form to resolve this issue by making another episode of Frasier, one that was more obviously strange. Rather than relying on narrative diversions and off moments of dialogue, I decided to make a work of video art that would wholly break apart picture and audio, thus making an episode of primetime television that was not at all, as the title suggests, normal.

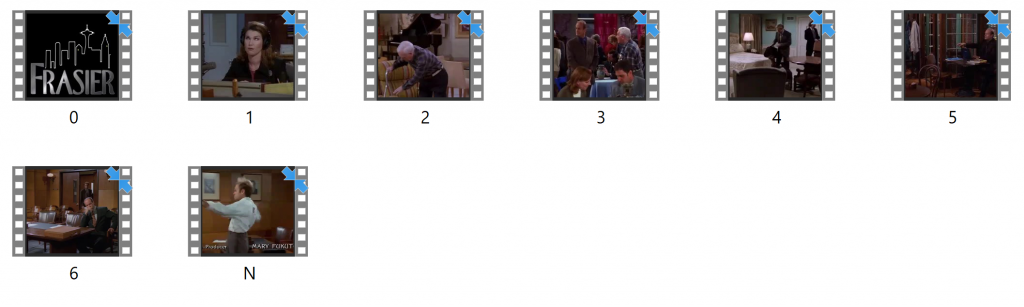

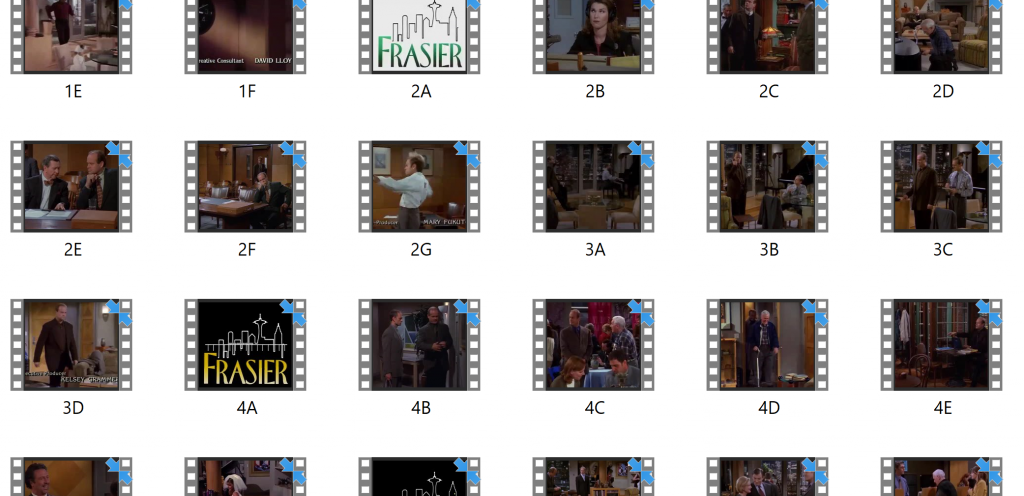

I began by taking five episodes of Frasier, chosen at random, and splitting them into their component parts (signalled, in the syntax of the show, through a fade-to-black, fade-from-black transition, sometimes accompanied by text). I ordered these parts chronologically, isolating the opening and closing sequences from each episode, as these segments were the only structural constant throughout the episodes. I then used a random number generator to order the middle parts, until I was left with a standard, 22-minute episode of Frasier.

These clips I used to construct the visual portion of the piece; for the audio, I converted the unused clips into .mp3 files, and matched each file to a video file by duration. I then merged the video clips with the audio files to create my normal episode of Frasier. This episode would have no structural throughline, no consistent plot, and no discernable connection between the visuals and the audio. It would thus occupy the language of the primetime television sitcom without any of the jokes. It would be a 22-minute slog that felt like forever, completely unfunny and a pain to actually sit down and watch. It would be terrible.

However, even this didn’t really come through in the piece. Because I had used clips from Frasier, people still felt as though they were missing a necessary context. It was still too close to the syntax of Frasier, outweighing the syntax of video art more broadly. This left me feeling both defeated and exhausted. For 3 weeks, I had been trying to come up with some new thing, some new spin on a work of conceptual art I had figured out on the first go-around. And nothing I made connected with anyone; I was locked into this Cheers extended universe, and I wanted to get out.

Form 3. NILES

When it came time to make my final form, I was lost at first. I didn’t want to make any more Frasier art. It wasn’t funny anymore, and I was tired. But then, I had a revelation: I would take the syntactical dissonance of my original evidence (the thing that made it funny), and merge it with the literal text of the NILES spec script, using the form of video as seen in A NORMAL EPISODE OF FRASIER. I would thus combine all my forms to make one final form that embodied everything I was trying to do: I would make a work of hyper-pretentious, avant-garde filmmaking, under the pretense that it was a spin-off of Frasier that would air primetime on CBS every Thursday night. Of course, I had been working under the assumption that this was a “final” form, and was supposed to combine elements from every previous form into an end product; I was not thinking of it as a “third” form, one that was supposed to add a system of values to the evidence. By the time I learned this, I had already filmed everything, and so I just had to roll with it.

And I think it largely worked. By adding a non-Frasier visual element, I was able to distance the work enough from the language of Frasier itself so as to appeal to an audience that had not seen this beloved sitcom. I was also able to re-emphasize the dissonant context at the heart of this project: to say that this weird art film was picked up by CBS and would exist as part of the Cheers universe is kind of funny, in much the same way that a thorough, hyper-detailed, scientific paper being written about the sitcom Cheers is kind of funny. It used the formic elements of the previous iterations, and brought the joke at the heart of the original evidence, and combined it all into something that really worked.

Conclusion.

While I do think this project ultimately worked out, I did have a tremendous amount of difficulty with it. But I don’t necessarily know if this difficulty is inherent to conceptual art as a whole. In fact, I think it would be reductive to say that what I learned from this experience was that “conceptual art is hard actually.” Rather, I think that certain modes of making conceptual art are more difficult for some than others. For me, collecting evidence and trying out different forms is incredibly difficult, because it does not enable things to “come together naturally,” as I think of it. I find it much easier to just have an idea and do it, without any extraneous breaking-down of that idea. I’m used to just doing things, and either they work or they don’t. And it was for this reason, more than anything else, that I found this process of “finding a form” difficult; it’s a process that just does not work with my brain.