At first, when given the “finding a form” assignment I moved to present some form of evidence in an effective way, to affect, through my evidence, a specific impression on the viewer. Given work and discussions already had in class, I interpreted this prompt as a way to practice refining my associations to a specific point.

I decided to hark back on ideas thought about standing alone in front of a Victoria’s Secret during my sophomore year of college. Late at night, in the Cross County mall, no one was around me. I was fulfilling a suburban legend. These conflicting themes, of fulfilling childhood legend through an actualization of a prepubescent taboo. I thought this would be a good concept to work with through the representation of a form of evidence. Ultimately, that evidence came in the form of three, wide-angle videos shot of myself standing outside the three closest Victoria’s Secret’s locations to me.

Late at night, I went out in a shirt and jacket and videotaped myself standing, looking; just, pacing around the three closest Victoria’s Secret’s to me. People on the streets of Manhattan walk and pass my camera, as I move around the space, the persona focused on the evidence of the building; its contents, structures, and messages.

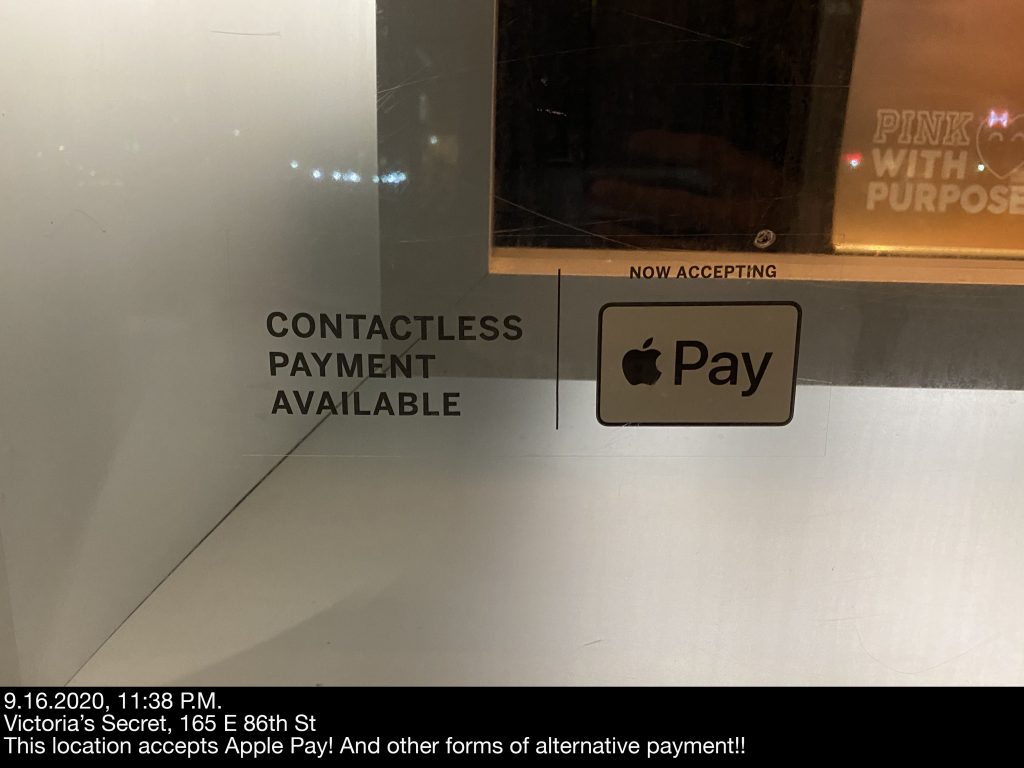

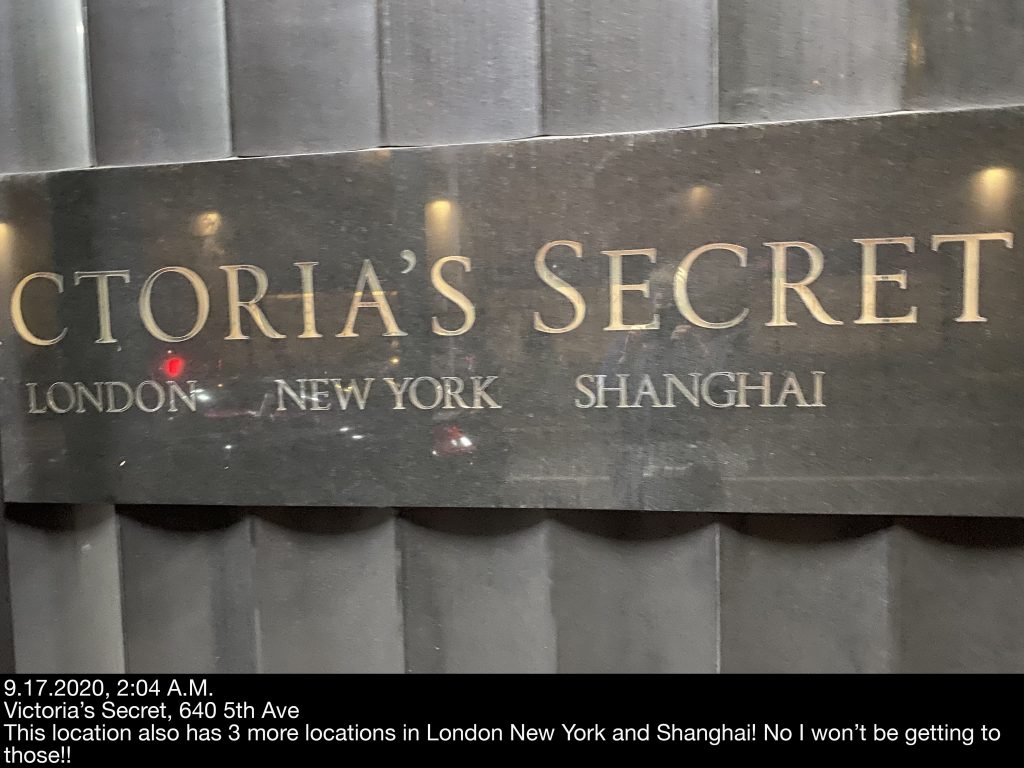

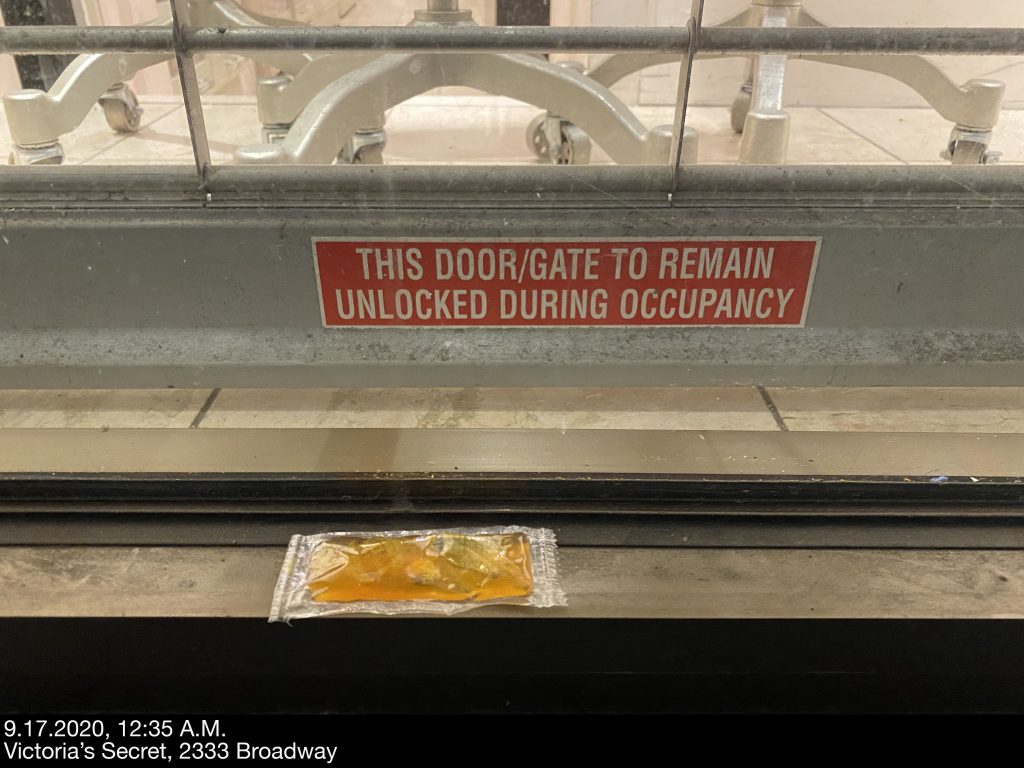

To couple with this seven-minute-long video of me in front of the three locations, I also included pictures, took seemingly on a smartphone, of small details of each location, each with distinct black, captions naming the date, time, and location of each photograph. On some, there is also a sentence or two beneath, which could function as a description.

I presented these forms all at once to the class without any context; of course I ordered them in a specific sequence relative to their time and place, but other than that, I left the associations out there and I wanted to see what was communicating. I wanted to see if people felt the gravity of that moment, watching it take place through an other. That childhood history of knowing not to stand and look inside the Victoria’s Secret. People figure out this history and nuance presented in this stark, evidence based format; almost like surveillance footage. What is Victoria’s Secret?

The reception from the class seemed to exceed expectations. People were into the conflicts I was arising. The performative nature of it, it’s voyeuristic feel, and questions about gender and physical space came up in conversation. Borders, was a word someone used in critique that I thought was especially relevant. A lot of my ideas were communicated and my form felt strong. I could expand this beginning piece into a larger project if I wanted to, incorporating more locations. It was a thrill when I was actually there. Random occurrences happen when you make work in this public form that you don’t anticipate. These occurrences then inspire to think differently about work in the future. Like when I was out there, standing in front of the store, factors emerged out of the stream of things. There was a cop car outside one location. Two of them were inside, watching me from across the street. A homeless man was sleeping in front of another. I had to think if I had the right to disturb him; how close can I go? When I arrived at the last location, deep into the night, it was all boarded up. Because of this, I was able to capture that spontaneous moment in the movie’s end, when I’m able to peel open the window and make eye contact with the model inside.

It was a solid form to convey my evidence, so when Angela said that, for the next week, we had to put our evidence into a new form, I got kind of worried. In truth, I didn’t want to put this piece into a new form. Through my video/photo series, I was already able to make a compelling piece. If the project were to really progress, I would have to stand in front of all the Victoria’s Secrets locations in New York, and if I followed through with it, it could be a thought-provoking piece about childhood stigmas, gender, sexuality, and borders.

However, I didn’t really want to stand in front of anymore Victoria’s Secrets. I realized, I didn’t want to make four more versions of this piece about gender, sexuality, and borders. In reality, the first time I stood in front of the Victoria’s Secret alone sophomore year, it was originally about the actualization of childhood legend. This legend, of course, is inherently associated with the pubescent and sexual, but to my own feelings, this moment never felt predatory. It was almost like, big whoop. There’s nothing wrong with standing in front of Victoria’s Secret. Breaking a childhood stigma, like I haven’t seen any of this before? And who makes a big deal about it? The people walking past? The people in class watching the evidence? Standing there, almost just taking in the store’s light, like I just stumbled upon it and now that moment is in front of me. This specific legend is inherently sexual and gender-based, and these themes were half of my original intention. But for my evidence going forward, I wanted to make the “childhood legend” aspect of the Victoria’s Secret more visible, because the other aspects seemed to have come on much stronger. I needed to put this piece in conversation with other forms related to the common familiarity of childhood legend, rather than the pubescent and gender-based scenarios of that shared history.

This would prove more difficult than I anticipated. Over the next week, I struggled every night to come up with a pathway out of my original evidence that wouldn’t involve the logical furthering of filming myself in front of more locations. Ultimately, as class neared, I couldn’t find the answer, no matter how much writing and planning I aimlessly sketched into my notebook.

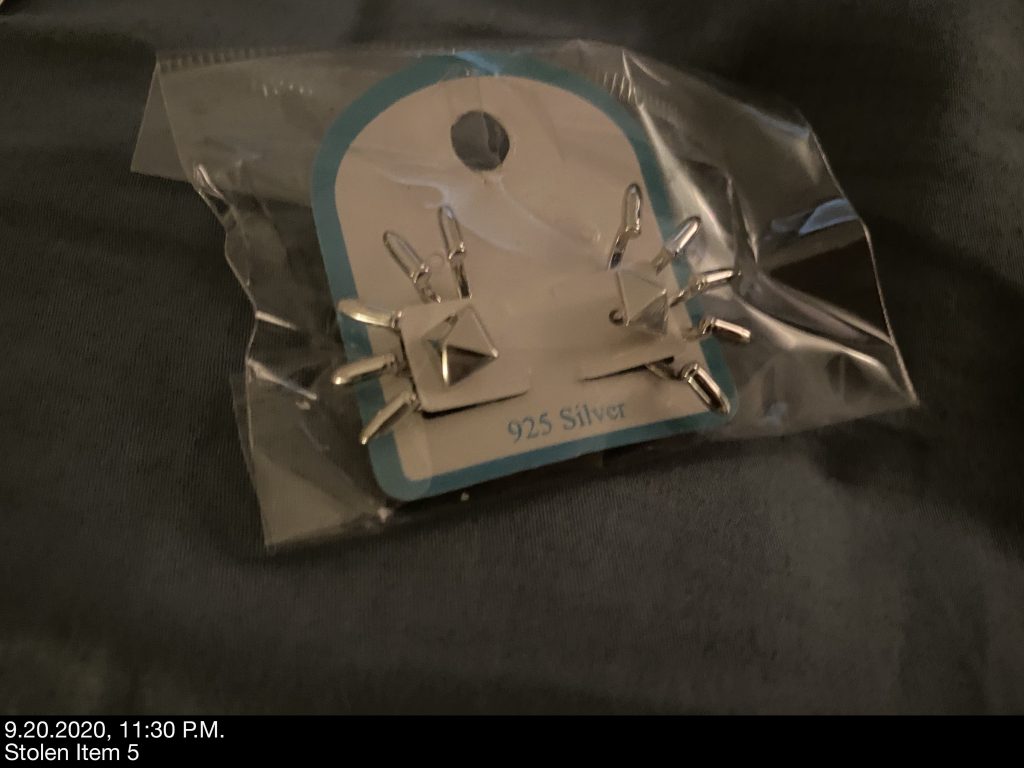

Instead, I decided to lean into everyone’s associations, and my next form of evidence that week was a series of pictures of “stolen items”, claimed to be in their captions. The items I curated were mostly associated with femininity: earrings, bracelets, necklaces. I even included a photo of seemingly the same persona from the Victoria’s Secret universe barely fitting into a pair of fishnets.

The class received it the way they should’ve. My progression from form to form was easy to follow. I was not satisfied however. It felt like a cop-out.

At the end of class, Angela suggested that for our next form we take our evidence somewhere unrecognizable. I remember her suggesting the idea of a dollhouse; how can we represent our evidence in the form of a dollhouse? This got me thinking. Again, I began to brainstorm in my notebook about how I could continue, in a new form, to really express the ideas of common familiarity in childhood legend, and balance the associative damage I’d already done.

This time, I came up with something I liked. My solution was a piece I’d deem simply, Evidence. For class, I decided to have evidence placed in front of me that seemed to be brownies in a normal white pan, cut up into eight, equal pieces, perfectly cut and perfectly baked. I wanted these “brownies” to be aesthetically perfect, not in the sense that they are extravagant or decadent with sprinkles and candy, their appearance is quite homey, in reality; simple and plain-spoken, but organized and stunning nonetheless.

I arranged for my evidence to be placed in front of me at the start of critique. I was to not interact with it. I was to not touch it, or smell it, or taste it. The seemingly perfect, fudge top-crust was not to be broken; it’s contents and mechanics, not to be engaged with. This evidence was meant to convey “brownies”, and I had brought them to “class”.

I wanted the class to watch me sit in front of what seemed to be brownies. I wanted to invoke whatever associations my class had with beautiful brownies being placed in front of them. This shared childhood legend of a giant pan of fresh brownies. But in front of me is only my evidence. If I don’t interact with it at all, how do they know it is brownies? If they can’t physically validate them themselves, and I don’t touch them or taste them, breaking the pretty crust, I give them no validation of their existence as brownies. My classmates are not present to touch, eat, and smell them themselves, however, they are present in class, and I have brought them to “class”; what seem to be “brownies”. They have to watch me sit in front of them. This conflicts in them the childhood legend of fresh brownies being placed in front of them, putting them in my shoes, and on top of this, the idea that they are voyeuristically watching someone placed behind an uncanny version of this common, childhood symbol.

This piece ended up being well-received in critique. People touched upon the ideas of watching me sitting in front of what seemed to be brownies, and how especially good they looked. People said the beautiful, untouched crust even reminded them of the closed Victoria’s Secret doors, and someone even raised the scenario in their head of, “How is Owen going to eat all those,” which I thought was especially interesting. But along with this affirming reception, of course there were also people who felt that the piece was a bit abrupt, in regards to its shift from my earlier forms. However, this is exactly what I wanted to do. I wanted to put this work in automatic conversation with my other forms, Victoria’s Secret and “stolen items”, in order to bring to light more of the childhood legend aspects of those forms. So, in the end, I felt successful here.

For my evidence’s final form, I figured out what I was to do about a week and a half before it’s final execution. I decided, as a new form for my evidence, I wanted to use my location at the moment of class as my medium. I thought, that if had my class watch me have class somewhere, and have direct access to my exact location from beginning to end, I could really flip this voyeuristic feel on its head; especially, if at the same time, I filmed with a different wide-anlge lense a couple feet away from me, taking a shot of me sitting with my laptop in class. In a way, I was taking my entire class to a new location, and through the separate video, to be put up on the drive after class, I was going to make my class watch themselves have class in my location.

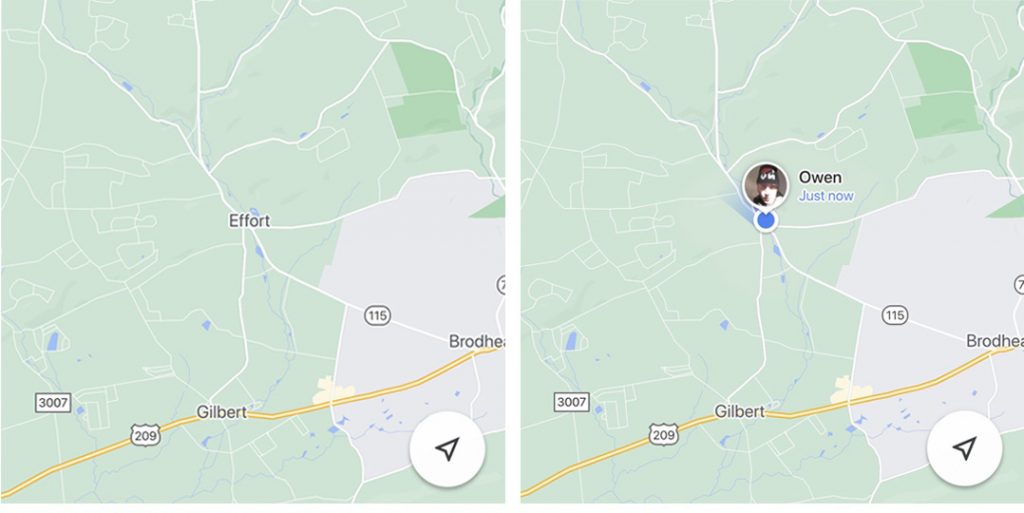

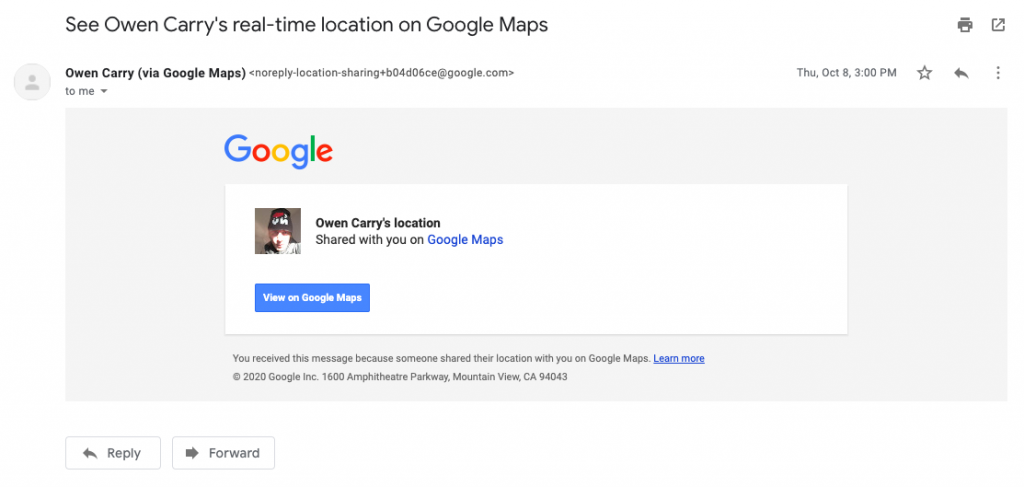

A week out, I decided to take class in Effort, PA, about a four-hour commute from my home in Manhattan. To get there, it would require me to commute out of New York, taking the subway, and then the train, making a transfer at Seacuacus on my way to Rockland County, where my car is parked at a family friend’s house. From there, I drove to Effort, early in the morning, and scouted a location for myself to take class. Ideally, I ended up getting a connection on the exact spot on Google Maps where, Effort, is watermarked over the town.

So at the time of class, I emailed a link to my exact location to everyone simultaneously and separately. I didn’t actually present my piece until the end of class, however. For two and a half hours I sat in front of this river in Effort, PA, taking notes, eating snacks, and participating when I wanted to. Before class, I decided I was not going to volunteer to go. If we ran out of time, we would simply run out of time, and I would have had class in Effort, PA, and they would have watched me have class in Effort, PA, and I would still upload the video of them in class on the Drive.

Luckily I guess, I was asked to go before class ended, and people were very intrigued by my evidence. Some people revealed how they first felt when they got the email at the beginning of class. Some thought I had made a mistake; pressed the wrong button. I could see them giggle or smile when they got it, or when they heard the river and cars in the background behind me when I volunteered to speak during class. In a way, my piece infiltrated everyone’s critique that day.

And people said they felt weird, knowing my exact location, watching me on the screen. And I had gone to Effort, not put in effort; a fun play on words that the piece brought to question. This idea of awe in art I was attacking. I wanted my class to be in awe that I was somewhere else. And, I was that somewhere else, to them. To them, I was Effort, PA; right on the watermark by the river.

This form seemed effective, and Effort, PA, seemed to be the best closer for my evidence. In the end, people had veered away from their original discussions of stigmas associated with my Victoria’s Secret project, and they more understood my ideas about shared knowledge of childhood legends and stigmas, watching them be broken, and the dissociative, uncanny feel of my representation of them, which further complimented the contradicting sentiment. I left Effort, and this “finding a form” project as whole, with a feeling of control over my art’s associations, as well as many new ideas and motifs to work with going forward, realized through the production of work that challenged me to think in new forms of expression in art, like brownies and location. I developed a lot over the course of this project, struggling for a moment in the middle, but I’m glad I kept thinking, and writing, and challenging myself to come up with a more solid language and a stronger concept for my evidence.

-Owen Carry