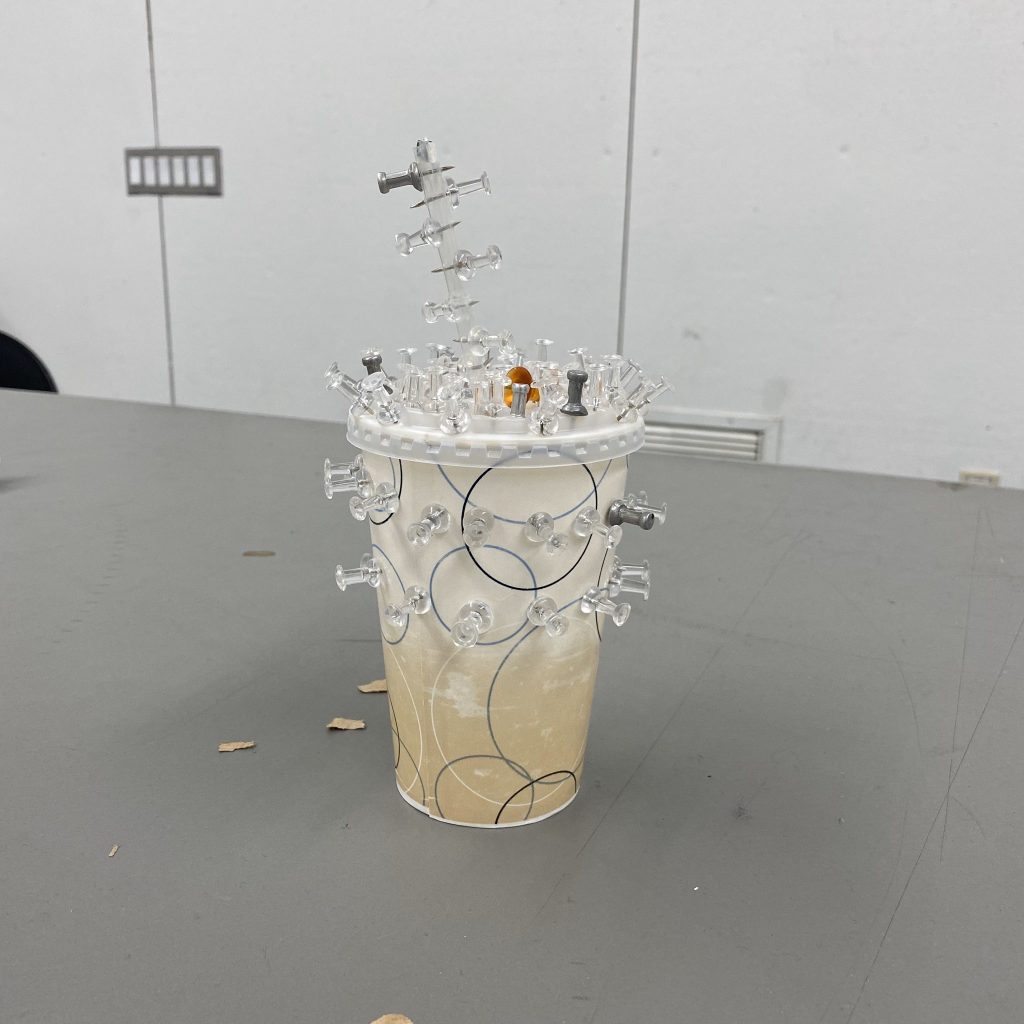

I first began to flirt with push-pin art at the end of last school year when, bored between classes, I decorated a pub cup with push-pins taken from the room’s jar. In every room in Heimbold, there are push-pins dumped into plastic tubs, holding their clear forms for us to use when we hang our work. They’re a visual symbol of all art buildings everywhere; the unsung hero of work on a wall.

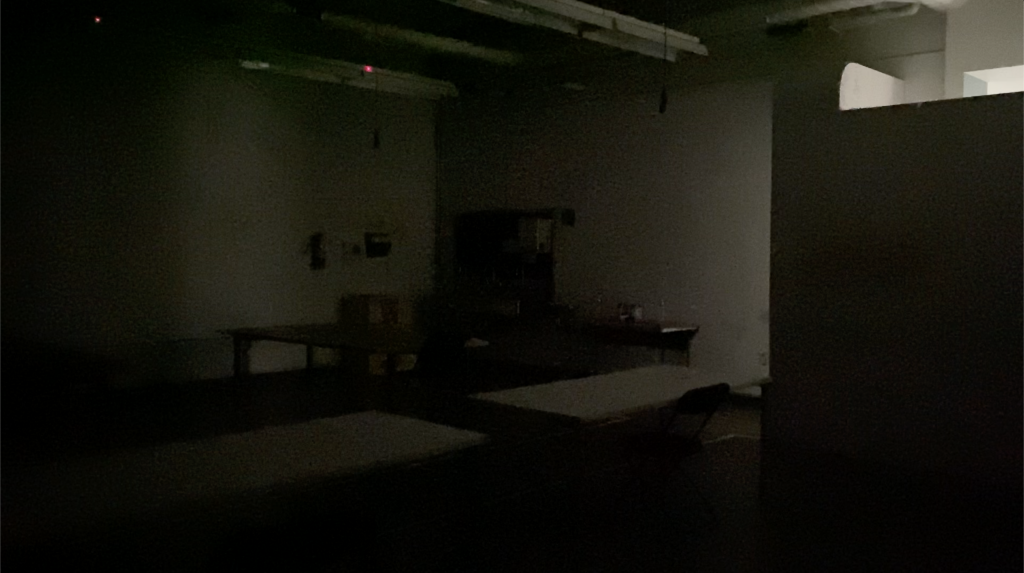

When Covid hit and the world stopped, the first time I’d been to Sarah Lawrence since we’d left was in September to get tested. Afterward, I walked over to Heimbold for old time’s sake, to see what was inside. Maybe there’d be someone I knew working the front desk or a familiar piece on the wall. But the place was empty without a trace of anyone. My footsteps echoed off the empty walls and push-pins rattled when I shook the floor.

It was so sad. I began to feel depressed about my time at Sarah Lawrence. All the years I had been there, now sitting on the side of Kimball Ave, watching nameless freshman run the length of it; I felt like I was going to go out like a whisper. None of them would know of Heimbold; just another building on the campus.

That’s when the idea of push-pin art began to surface in my head again. I thought, how can I compliment the emptiness of Heimbold? What kind of work could visually complement a space like that; empty, devoid, and filled with my own emotions about a dwindling senior year in a place that was forgetting me (these emotions hopefully shared by others). Push-pins could fill the walls of this place, reclaiming it, growing on everything like lichen, as if they were bored between their classes; a mind of their own once everything’s gone and we’re all out.

I first got to practice with push-pin art again in an assignment in October where I spelled DON’T in push-pins on the wall of my apartment. Angela prompted us to “sell something,” an object, maybe bought from a store, and to find a way to sell it to the class. I thought it’d be funny to buy some push-pins and make them spell DON’T on the wall, and when it was my turn to present, I’d tell my class that I was looking to sell these push-pins. I’m just looking to get them off my hands. Is anyone interested? Don’t worry. They do this all the time…

It was kind of a performance piece over zoom, but also, I wanted to see if the language of push-pins was striking to the class. And it was ultimately. I had done a really good job of putting them in precisely, and everyone appreciated the work it took. They also thought the whole premise was funny and contradicting on itself. It was cool how I was able to inspire something out of just push-pins.

This made me more confident in the lasting power of push-pin art, so as I sat on top of the idea throughout the semester, I began to see how I could use push-pin art for my final conference project.

I wanted to go back to that moment of me in the empty Heimbold in September. How I could use push-pins to convey that? How I could use push-pins to inspire awe, turning the idea of awe on its face, because, they’re just push-pins. Taken out of the wall, the wall is returned and the push-pins are just another clump, thrown on top of one another in the plastic container, so someone else can hang up their artwork.

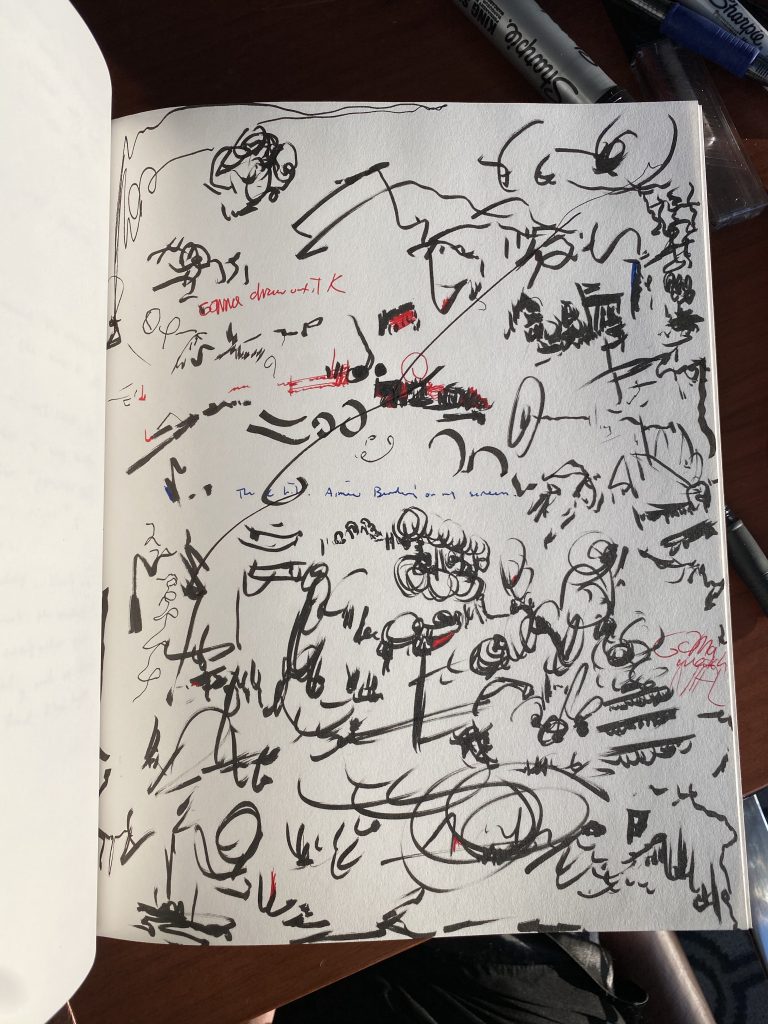

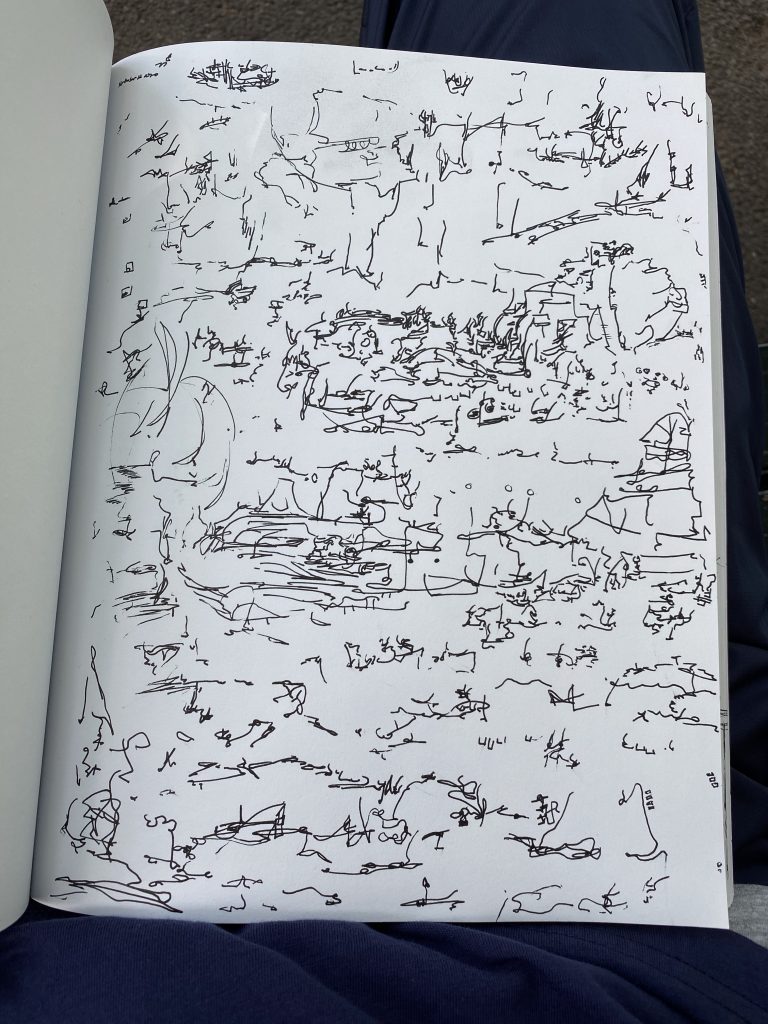

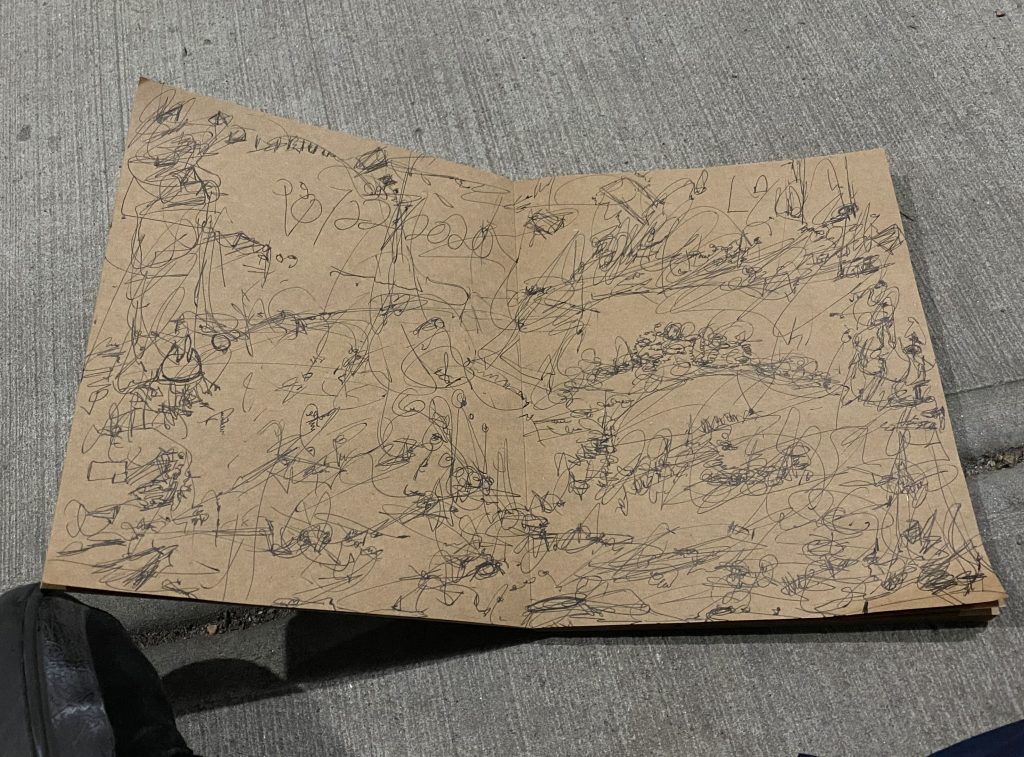

I pitched the push-pin idea to Angela, and luckily, she let me use 108 to practice in. And important to my conception of the piece, gradually throughout the semester, I had shed light on my drawings and drawing style to the class. How I’d be balancing the push-pins on the wall visually came a lot from these practices in my sketchbook, not of push-pins, but just of freelance drawings I had done here and there. A common question from the class was, what was it going to be of? What were the push-pins going to be on the wall? My class had seen me spell DON’T, but were the push-pins going to spell now?

I used my drawings to quell these worries, showing through them, my ability to balance a chaotic scene through lines and shapes that broke their own rules. When I’m in the middle of a drawing, I’m always trying to find that new shape, or line, or shading, that I’ve never done before. In the practice of them, I’m always breaking my own rules, inventing new ones, and then breaking those new ones too. My push-pin practice would follow this same ideology, and I hoped to learn a lot of new ways of putting push-pins in the wall.

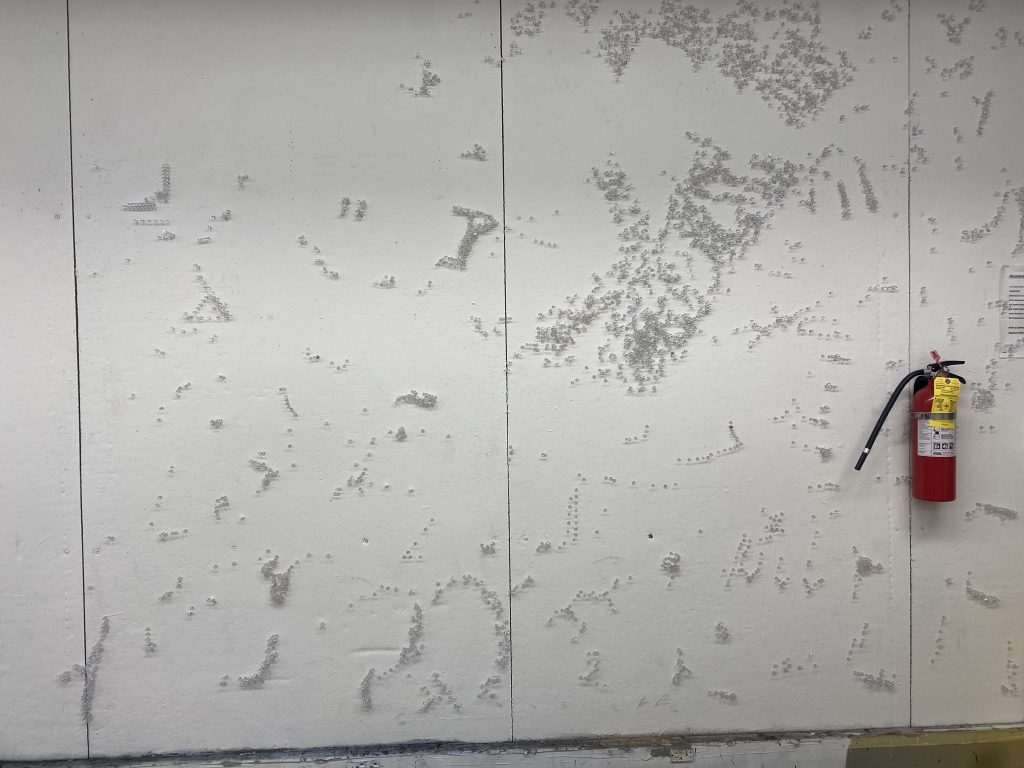

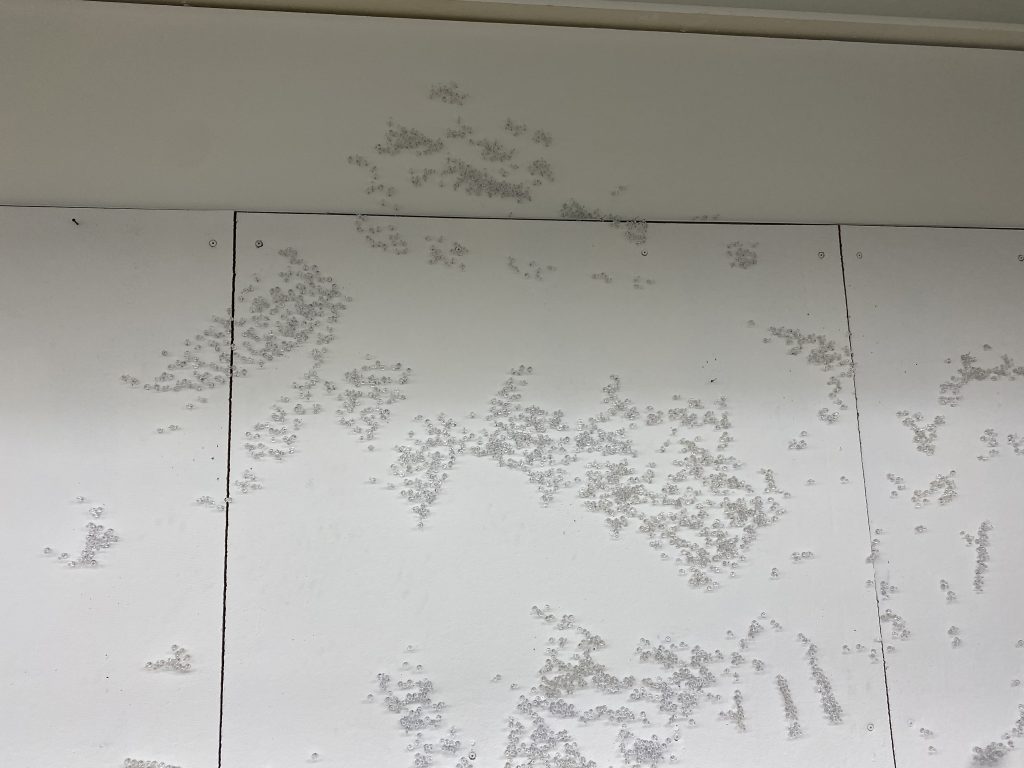

I began the first wall on October 29th in 108, just practicing with the medium. Little did I know, this first practice would turn into a sprawl around a corner of the room. I just kept seeing more and more places to put push-pins in. In corners of my eye, I saw inklings of new forms that could take shape. On my train rides home, I’d look over the pictures of the wall on my phone, seeing new places to start putting in more that I’d return to the next day. Slowly, the corners of my eye began seeing new places needed in the exploration.

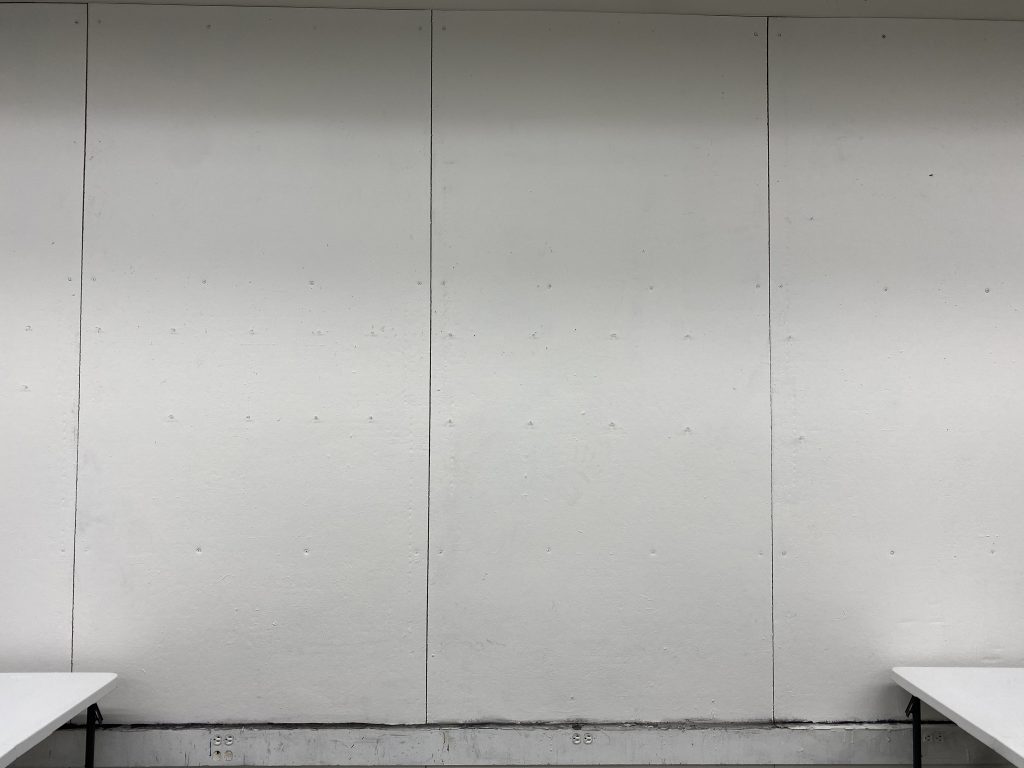

I began to devise a plan, or a route, that I wanted the push-pins to follow as I made it around the room. I presented these plans to the class in empty photos of the walls, not yet touched by push-pins, where they would eventually be pinned; their potential movement represented in arrows drawn on Photoshop. It was the route that I intended to follow, but of course, through the learning process of the medium, my own insistence of breaking my own rules, and the invention of new ways to put in push-pins for their own best interest, the plan was bound to deviate a little bit. But of course, it was great to have the skeleton in my head that I could follow throughout the next month or two before conference week finally came around.

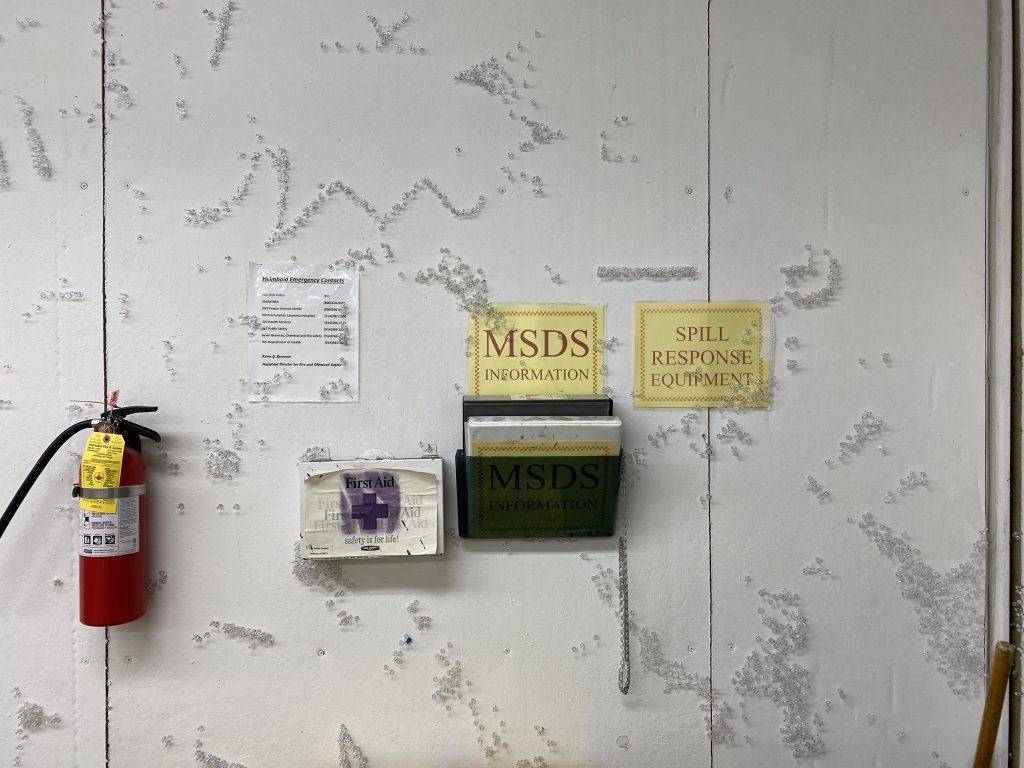

As I kept pushing, the pins began to run beneath the sink, over posters, behind cabinets that one could peak around and down to see a whole universe; a new way to look at them from up above, seeing their bodies in a new way stacked on top of one another through their clear membranes. They began to run underneath the room’s side table, with its hand sanitizer and plastic gloves, poking through the paper sheet that covered it, running down the wall behind it; the push-pins finding home against a new backdrop.

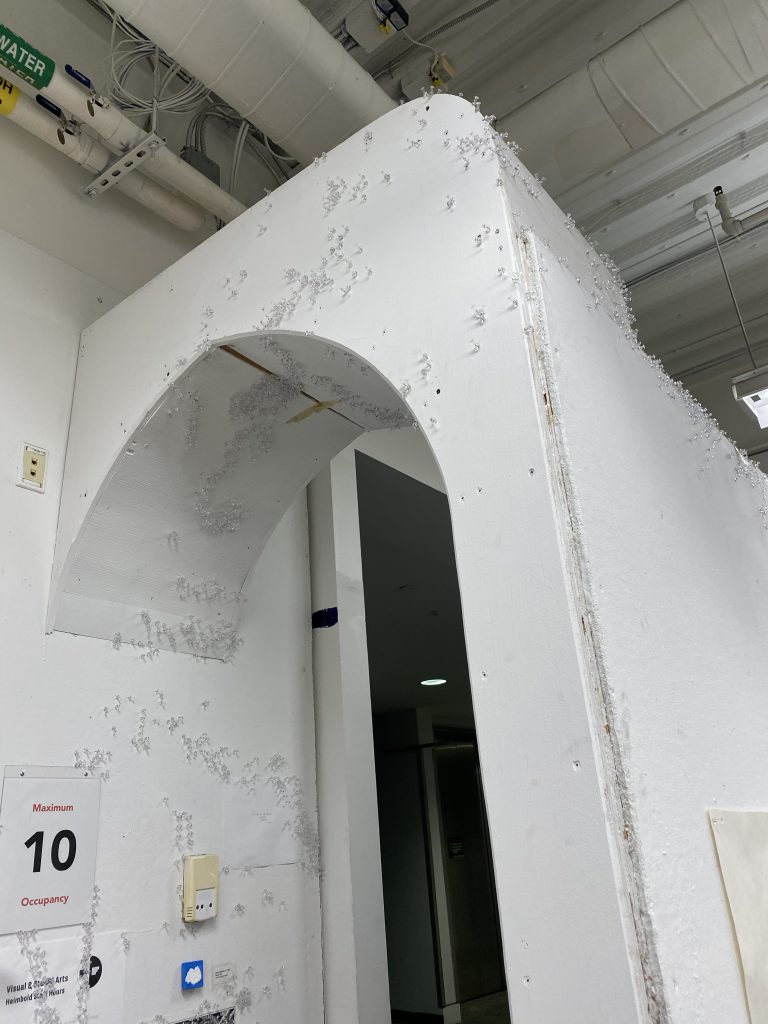

Eventually, I got to the loop around December 4th or so. Initially, I planned on just going around it, following its form completely to the wall that faced the hallway. But instead, I saw a different route, taking the push-pins around both sides of its top, almost splitting them like a Y, and having them meet back around themselves, to start filling the hallway wall together. Again, I saw this form/movement shaping in the moment of it, putting that first push-pin in where I hadn’t anticipated, and seeing the work break a rule that I hadn’t known yet.

Another thing I thought of through the process of it was where I’d end up as it moved to finish. I got the idea of filling the last wall of the room, spreading over the top corner of the hallway wall, with push-pins lined in a normal fashion, to eventually end the practice. On this last wall that I ended up on, the push-pins form in squares and rectangles like someone had just hung their drawings up, but when they took them down, they forgot to take the push-pins out with them. When they left the room, the push-pins stayed and began to grow, spreading over onto the hallway wall, sprawling up it and around the loop, swirling down beneath the table, under the sink, around the corner, and spreading themselves up into the far reaches of the soft wall, breaking even past that and onto the hard wall, too high for anyone to reach.

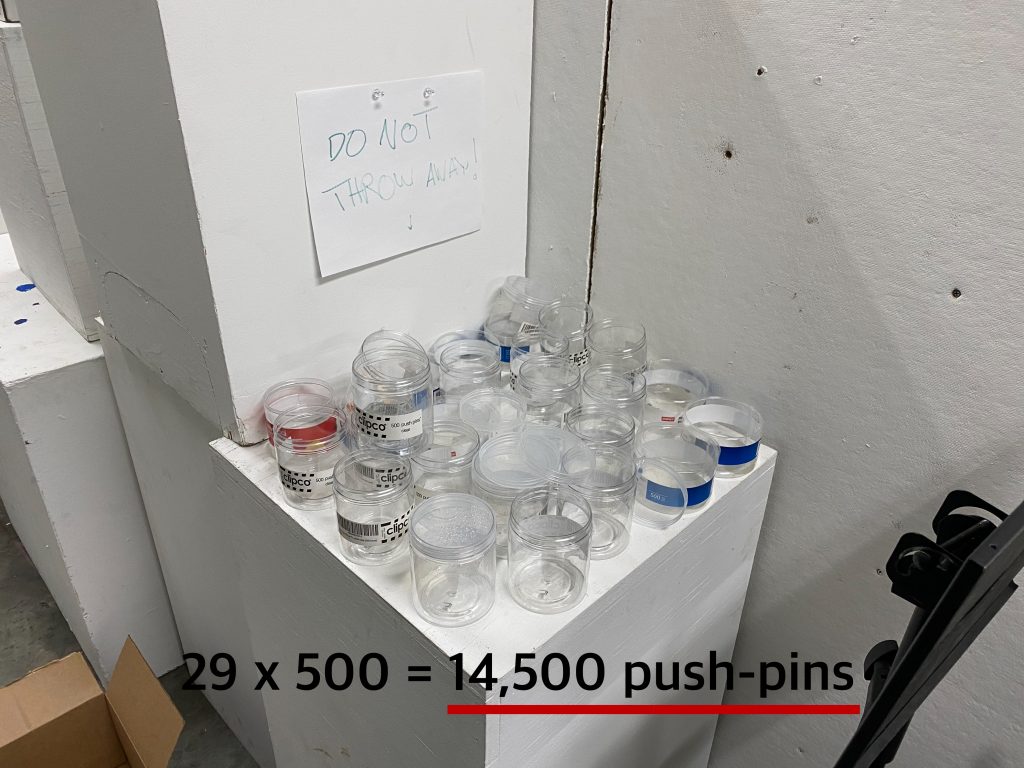

And with that, I felt the work was complete. I had gone through 29 tubs of push-pins in total. 29 tubs of 500 meant there were roughly 14,500 push-pins on the walls; give or take a couple that I might have swallowed.

And I was left with only one lonely tub of push-pins out of the lot that I had bought online, to leave inside the room, replacing the one that I had used initially. I thought about whether or not I should leave it; whether or not, We’re all out, should leave a tub of push-pins untouched in the room. But I made sure not to break the taped seal on this tub, and I thought this would preserve the sentiment of the work; as if these push-pins weren’t allowed to escape because they were trapped behind the jar.

I learned a lot about push-pins, and now I joke, if anyone needs help, I’m the one to call for all your push-pin chores. It did take a lot of time and energy to do this much pushing; up and down ladders, stepping back and forth from the wall to see if I had placed one right, coming back and thinking, No, and then moving it not even an inch, stepping back again and knowing it was right and onto the next one, maybe in a completely different direction of the wall. And I talked with Angela about the representation/documentation of this labor in relation to the piece; to inspire more awe in its sentiment. She suggested that the documentation of this labor could be important to the work.

But I thought about it, and decided that, for only a post like this would it be worthwhile to mention all the time. For me, this piece didn’t have to exist in the digital space. Inherently, it had to, in order for people to see it and conceptualize in their own homes around the world, but really, the piece exists inside Heimbold and for that space. The piece exists for that one person to stumble by and notice push-pins on the hallway wall. They’ll follow them into the room, where the motion light will turn itself on, and all of a sudden, the sprawl of them will be revealed. They’ll be able to see their origin on the first wall, how they spread and took over, and hopefully, the idea of me will never cross their mind. It’s as if they put themselves up, a mind of their own, when no one was there and, We’re all out. And they’ll inspire awe inherently through their scale.

When I presented the work in final critique, people had some great reactions. My favorite one was from one of my classmates who went to see the work in Heimbold when I wasn’t there. I guess I must have turned the motion light off the last time I had left because when she walked inside, she couldn’t find the light switch. She said she kind of gave up, and decided to just use her phone flashlight in the dark room instead. She came up close to the wall and looked at them through this light, them spreading on top of one another, up and over and behind places she could peer behind. I thought this visual, of her fiddling in the dark, was striking; it was a new way I hadn’t thought of viewing them. How it must have really felt like a cave’s entrance, growing with mold inside its walls, exploring them as if with a headlamp. Again, the piece began to break more rules that I didn’t know existed. How I envisioned their presentation was even up to be broken. She had invented a new way, through accident and genius, to see the work entirely differently.

And I wasn’t even able to be in Heimbold on Thursday the 17th when my final critique took place. I had originally planned, weeks in advance, to be in the room, like I had been for so many classes (with my mask on and the white walls behind me), to present the piece and my photo/video documentation of it. However, the first blizzard of the winter had other plans, and hit New York in perfect timing, closing the building on my presentation’s day, locking the push-pins inside its walls. But again, another accident to break my rules. How fitting, I then thought, that, of course, the push-pins had to be in Heimbold all alone on the day they were due for my grade point. Alone in the building, I imagined them, during class, spreading further, pushing to more parts, extending past where I had finished while the presentation of the “final” work takes place. Unbeknownst to us, they’re finishing themselves in the dark, fermenting longer over winter break, so when I come to take them down, they’ve spread to take the entire room.

-Owen Carry