Dear Music Box,

Your soft tinkering enchanted us as our mothers put us to sleep.

As children, we lost ourselves in your sweet ballads, your lullabies, and nursery rhymes.

Mesmerized by the endless revolutions of your gears, we spent our days cranking your handle. Watching your little metal teeth pluck the same melody we’d heard time and again. But still we turned your handle once more, waiting in anticipation for what we knew was the only song you’d ever sing, but still, we were enraptured.

You remind us of our youth, wasting our days away listening to music boxes. Playing the same fragment of the same song until you are forgotten on our bookshelves or swallowed by greedy storage boxes, nestled away with our teddy bears and old finger paintings. You are soft.

You are sweet, harmless, redolent of femininity. The antithesis of masculinity. You are timid. Benevolent. Where is your courage? You lack the nerve to even play a full song. You are fatally timid. A coward. Where is your daring? Your aggression? Why aren’t you crying out in reckless abandon? You are a distraction. You watched as we sat in front of you, wasting our precious youth with silly little toys. You no longer fill us with endless curiosity, a vibrancy, and audacity that now feels fleeting. You let us lose our grit, our passion. We don’t run through the streets, crying, shouting our passions to the world. Tearing into each other’s intellect in desperation. You let us slip into the mundane. We are idle. We can feel nothing but scorn for you, much like the women who cradle you in their delicate fingers, hypnotized by your revolutions as they lull their children to sleep.

It is these same women with their delicate constitutions who would simply crumble under the splendor of hearing a song in its entirety. They are too fragile, and perhaps the blame should fall on these women for the stagnation that plagues mankind.

Yes, much like those cowardly women you too can never grasp our endless devotion and violent fervor for innovation. We can not be complacent any longer.

We have wars to fight and passions worth dying for. We have revolutions to incite and women to scorn. But for now, any change will do. And you’ve been sitting on my desk for too many years, now it’s time to sing a different tune.

Dear Former Music Box,

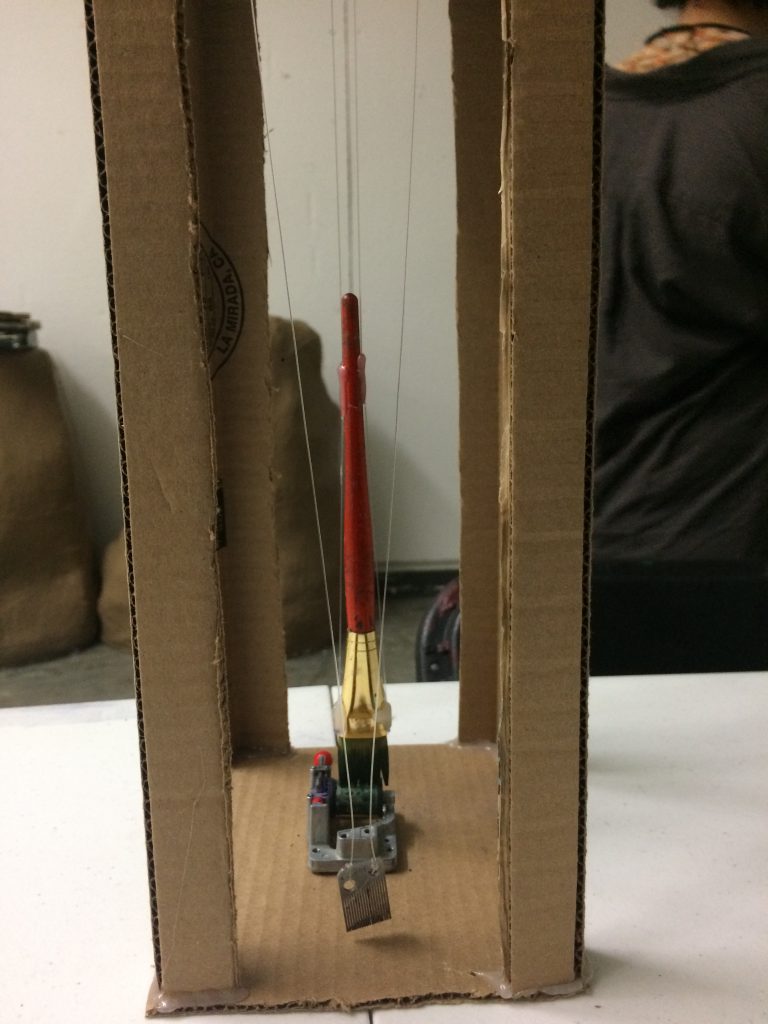

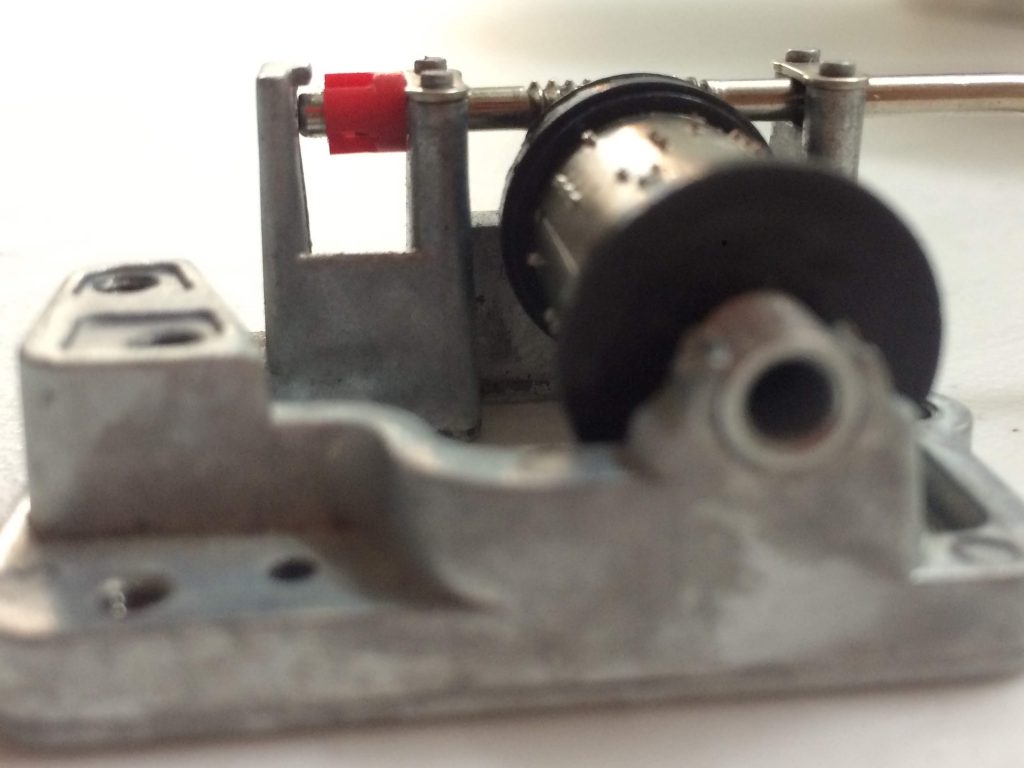

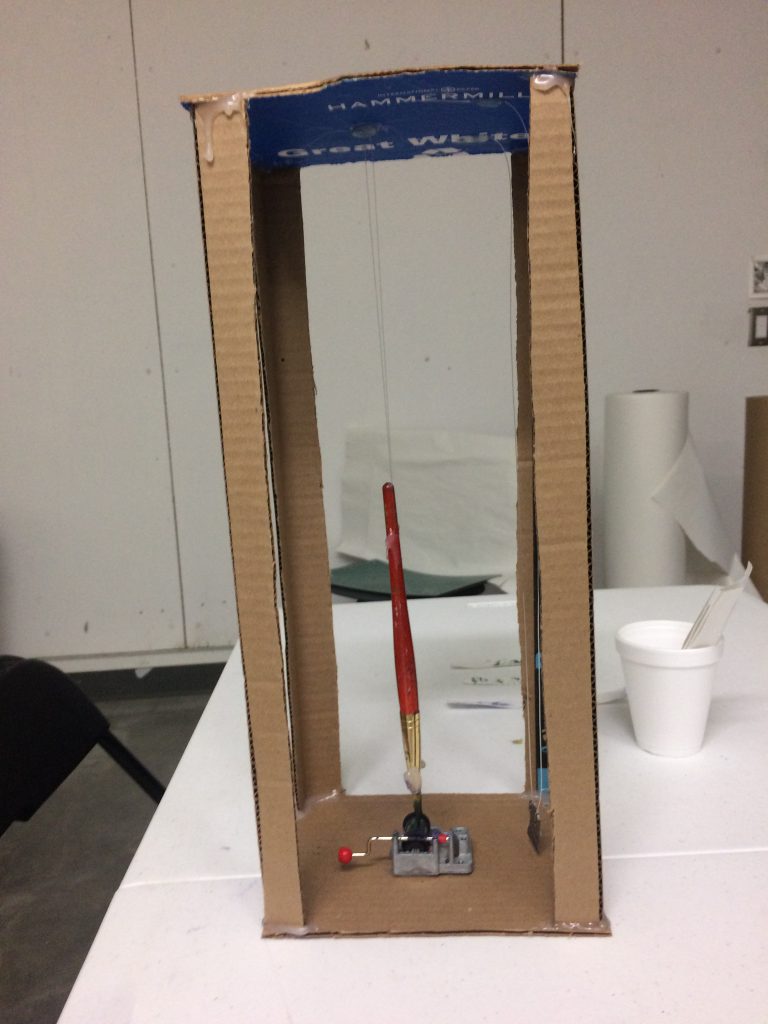

You may not be as functional as you once were. Your handle still works to turn your gears (if only because I can’t remove tiny metal bolts with my fingers).

I have to work a little harder to get you to make something beautiful. your parts no longer work in harmony with one another.

instead, they are scattered across this cardboard frame working only in isolation. but that’s okay because you no longer sit on my desk, collecting layers of dust.

I don’t have to look at you and deal with the nostalgia and guilt of neglecting you for so long.

instead, you have transformed into something productive. a product of creativity instead of a $1 souvenir with surprisingly strong bolts. instead of a 15-second melody, you now sing a new song of experimentation.

you may not be practical, but you are fun. you are a fun, useless machine.

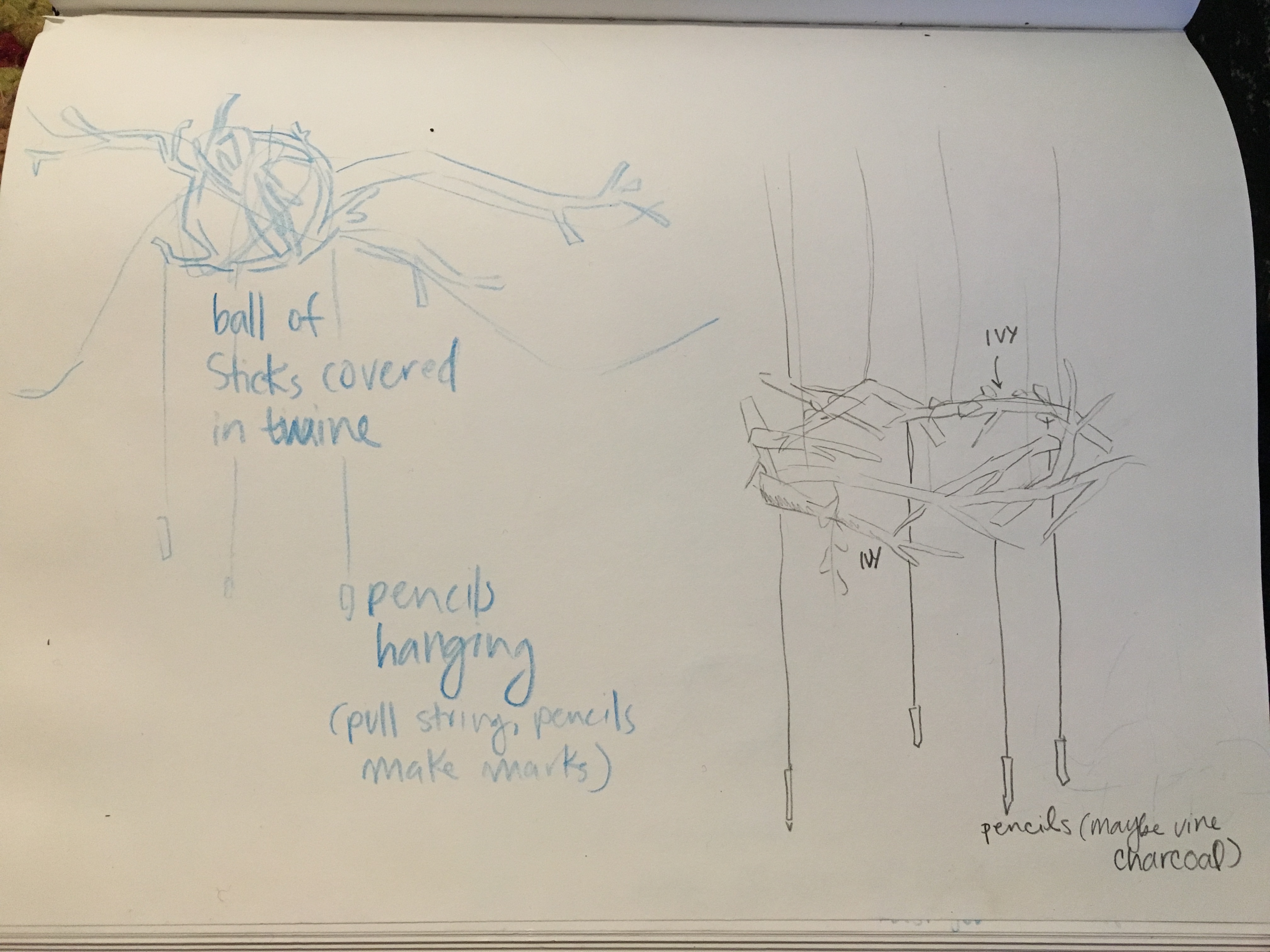

My new drawing machine was heavily inspired by Bruno Munari’s Useless Machines series. When rereading Machine Art in the Twentieth Century by Andreas Broeckmann I noticed a section titled “Bruno Munari’s Art of Machines” that hadn’t stood out to me the first time I read it. In the section, Broeckmann explains that Munari believed people lacked a proper understanding of machines and their behavior. He worried about humanity’s relationship with machines and insisted that it was the artists’ responsibility to save humanity by “understanding the anatomy of machines, the language of machines, their nature…” and finally to “re-route [machines] into functioning in irregular ways to create works of art with the machines themselves, using their own means.” After having worked with my machine for a couple weeks I can better understand what Munari is trying to say, but I still don’t know how much I agree with him. I think his sense of urgency about learning machines behavior and artists having the responsibility of harnessing the machine was a product of his time. He was a third-wave futurist who witnessed the relationship between the first and second-wave futurists and machines, and I think that had a huge influence on his own relationship with machine art.

I do agree with his belief that artists should try to learn the language of machines and turn it into art, but not for the same reasons. In the section “Concepts of the Machine in the Twentieth Century”, Broeckmann brings up the relationship and constant comparison between machines and the human body. Having constructed my drawing machine and worked with it for for a couple weeks, I’m starting to see the relationship between machines and bodies. Spending time learning the little quirks of my machine, finding out how to best operate it did at times feel like I was getting to know the machine as a person. Especially when you’re using a machine to create art, it can be hard not to begin to see the machine as an extension of your body.