For my Vision Machine project I chose to create a stereographic viewer, that when used can simulate a three dimensional image in two dimensions. I chose this, because I felt that given the materials that I could chose from it would be easier to create a machine that did not rely on movement to create a visual illusion, but also because they are the earliest predecessor to the virtual reality headsets that have become very popular. This ended up being a good call, because the machine I created worked very well and did exactly what I was hoping it would do.

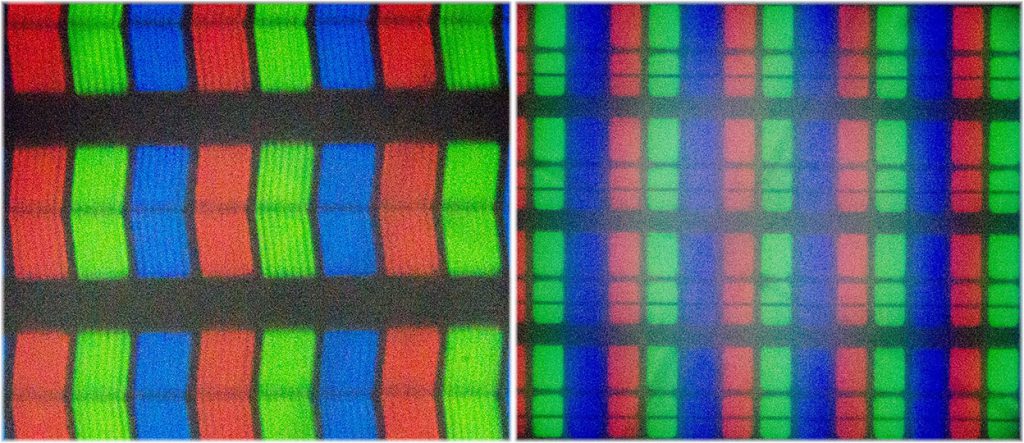

A stereographic viewer, or a stereoscope, works only when viewing a pair stereographic images. These are two individual images, one of which depicts the right eye view, and the other the left eye view. When these two images are combined they create the illusion of a three dimensional image. The role of the stereoscope is to place these images the proper distance and orientation from the eyes so that they can be viewed properly. The major difference between stereoscopes and most other early 3 dimensions vision machines is that the stereoscope does not rely on transparent images to give the illusion of dimensionality.

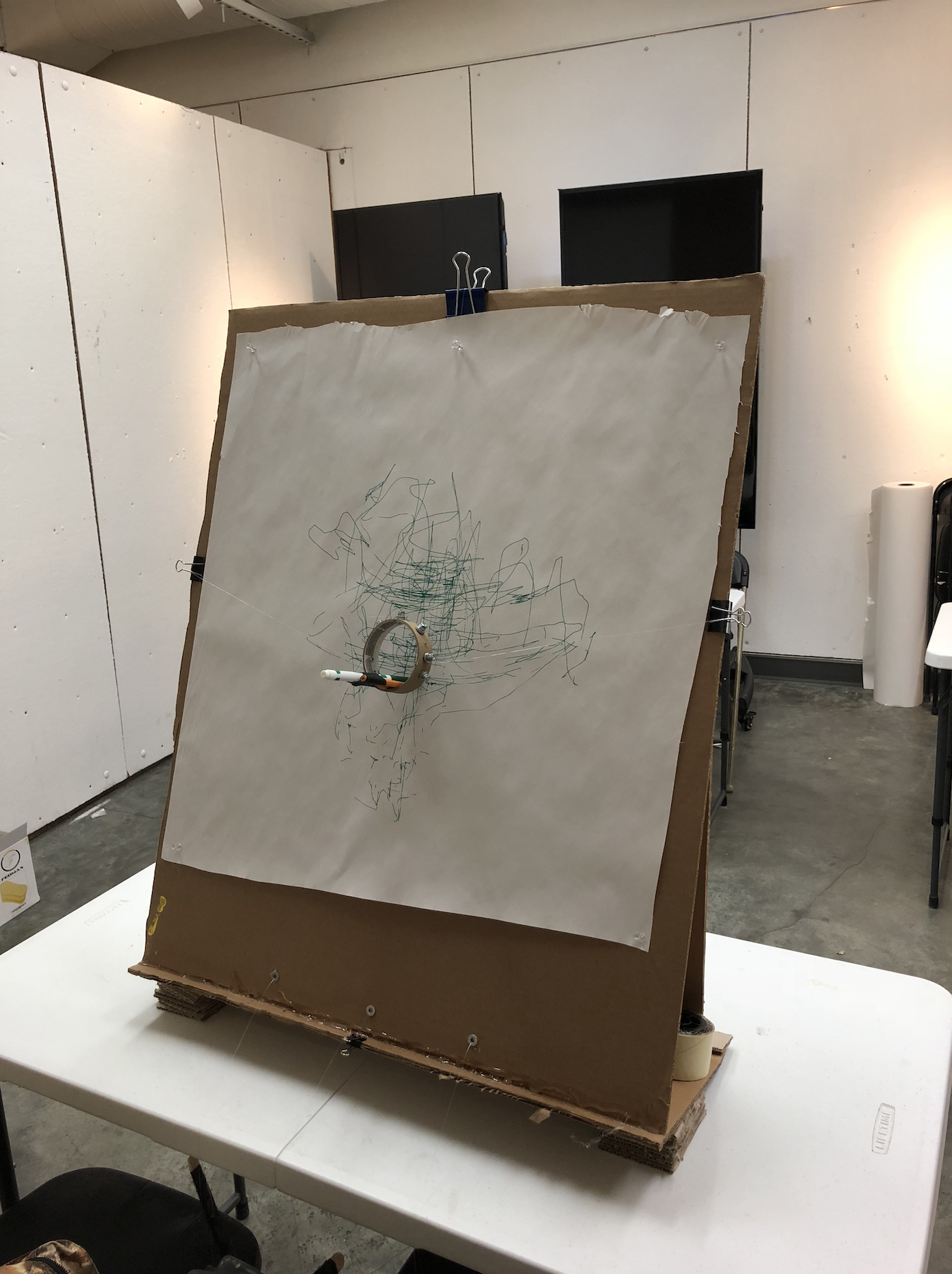

The first step of the project was constructing a frame for the device that would allow me to fine tune the distances and orientation of the image frame so that I could perfect the image. Inspired by the Holmes model of stereoscope from the 1860s I chose to use dowels as the base for my device, and by drilling pilot holes I was able to screw them together gently. After I created the frame I mounted to pieces of cardboard at opposite ends of the dowel. I kept one slightly loose so that it could be adjusted to the perfect place. After cutting holes in the first piece of cardboard I placed the images that I’d made on the other piece, and after a bit of adjustment I was able to see the three dimensional illusion. After advice from Angela I colored the right image red and the left image green. This helped immensely in rendering the image in three dimensions.

While building this machine I thought a lot about the reading I had recently done in chapter four of Andreas Broeckmann’s book Machine Art in the Twentieth Century. I thought specifically about the concept of “operational images”, coined around 2003 by German filmmaker Harun Farocki “images that are not simply meant to reproduce something, but instead are part of an operation. The purpose of these stereographic images is radically different than the purpose of normal imagery. These images do not serve a typical representational or explanatory purpose, but instead serve the machine itself. The image viewed through the stereoscope is one devoid of meaning, because it’s content has been subverted by the machine. The goal of any stereographic image is to demonstrate the functionality of the stereograph, not display its own content.

This goes hand in hand with Paul Virilio’s comments on how machines process images differently than humans. Virilio emphasizes the fact that the visuality of technology is fundamentally different from that of humans, “Don’t forget, though, that “image” is just an empty word here since the machine’s interpretation has nothing to do with normal vision (to put it mildly!). For the computer, the optically active electron image is merely a series of coded impulses whose configuration we cannot begin to imagine since, in this “automation of perception,” image feedback is no longer assured.”

Though the stereoscope is a far cry from the military imaging technologies that Virilio and Faroki discuss the core message is still the same, once images are viewed through the lens of the device their meaning is drastically altered. Despite its relative simplicity, the stereoscope is the beginning of the era of commercially available machines with the sole purpose of viewing images.