I, like most people in the world, don’t really know what to do about the fact that everyone seems to be sad.

Within my everyday social circles (taking into account that I interact mainly with millenials and Gen Z), I may ask how someone is doing. If they say they’re sad, or mad, or upset, I may ask if there’s anything I can do. Usually there isn’t: it’s the workload, or the weather, or the current political regime. And then I will encounter someone who is happy, and often they will deliver the news as if they themselves are shocked that they feel something other than unhappy. Perpetually happy people are like aliens to us—we can’t fathom that anyone could retain such an optimistic spirit without experiencing some kind of fundamental ignorance about the world.

Any moment of joy, then, feels like a subversion of the systems that force us to disregard our own happiness in order to attain more arbitrary “success,” as the “self-care as activism” movement has begun to define. Sometimes it seems that there truly is nothing that today’s wearied yet agitated youth can do, except focus on one joyful moment at a time.

I decided, for my conference project, that I wanted to pick apart this slippery emotion of joy—as a scientist or psychologist might—and see if I could tap the surface of what it means to me, and to others around me.

I began my research with the work of designer and author Ingrid Fetell Lee. Lee has formed a body of research around joy and its Gestalt psychology-like principles, essentializing that humans are evolutionarily predisposed to find certain shapes, colors, and textures more immediately pleasing than others. In her blog (The Aesthetics of Joy), book (Joyful) and TED talk, she speaks of items such as confetti, ice cream cones, bouncy balls, and every shade of the rainbow as sources of unfettered happiness that transcend age, ethnicity, gender, and location. I was fascinated—especially when I realized that I have unconsciously leaned into these simplification techniques in my own scenic design work, to attempt to evoke subliminal feelings in audience members before any action happens onstage.

When searching for materials, I first settled on yarn. Ever since I was a child, yarn has brought me the kind of joy that Lee so prizes. The array of colors, the firm but yielding shape, the endless propensity for mischief (the strands go on and on, and get tangled so easily so quickly)—all have made seven-year-old me treat yarn as a precious thing, and twenty-one-year-old me realize what kind of look and feel I wanted my conference project to have. I also knew that it had to be big, and immediately noticeable. I wanted to carpet as much of Heimbold as possible in a shock of color, and close-up, have the installation be pleasant to touch and interact with. Thus, my research led me on to yarn bombing.

Yarn bombing, a movement founded by knitting enthusiast-turned-textile artist Magda Sayeg, is what the New York Times calls “graffiti’s cozy, feminine side.” It involves wrapping public structures, vehicles—anything you want, really—with colorful knitting. Occasionally, as described in this other NYT article, it has been criticized for having a negative impact on the environment and belittled for its status as a “cutesy…hipster fad,” which I think has to do with the volume of women who choose to make street art this way (and the volume of men who have historically been associated with “traditional” graffiti). I wasn’t deterred.

For inspiration on the actual design of my yarn monstrosity, I decided to pay a visit to a museum that seemed to align its mission to Lee’s theories about playfulness and joy.

The Color Factory NYC is a traveling exhibit with current exhibitions in New York City and Houston, Texas. A collaborative work that features commissions from the world’s leading architects in color and whimsy (paper artist Emmanuelle Moreaux, graphic designer Lakwena, illustrator (and cook!) Tamara Shopsin, cultural historian Kassia St. Clair, economist Andrew Kuo, object journalism exhibition/curator of weird Mmuseumm, and more), it advertises itself as “20,000 square feet [of] brand-new participatory installations of colors we’ve collected around the city—hues that invite curiosity, discovery and play.”

I went to the museum. I was curious, I discovered, and I played. But I left Color Factory NYC somewhat unsatisfied.

Despite the sense of spontaneous fun that the exhibit tried (and mostly succeeded) to elicit, the experience felt extremely curated. There were photo booths set up in almost every room to maximize the “Instagrammable” experience, which made me feel pressured to capture a moment and save it for later rather than experiencing it in real time. All the gifts and treats and games I received or participated in began to feel like a commercialized expense, rather than a surprise.

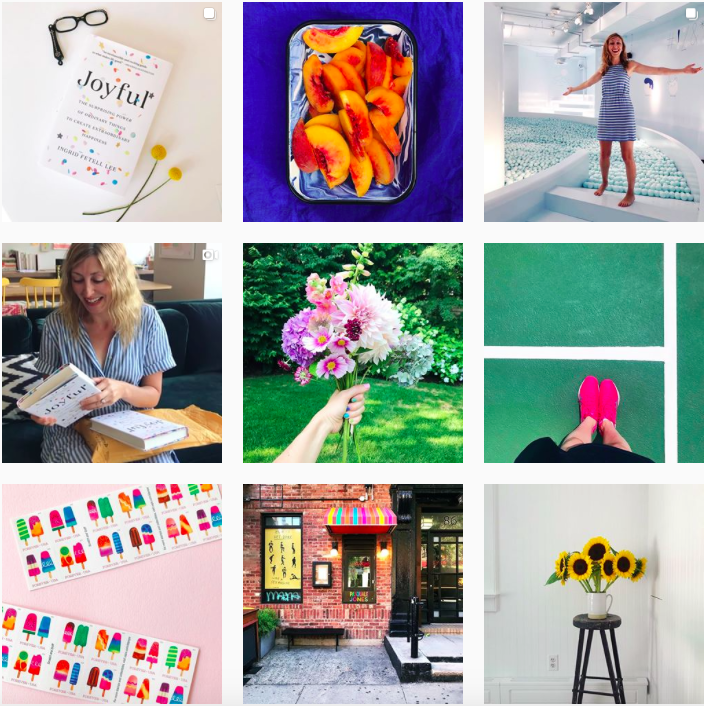

When I returned home, I did some Instagram surfing. Sure enough, the social media accounts of people like Ingrid Fetell Lee gave me the exact same feeling—of a carefully cultivated presence designed to boost engagement, not an organic source of delight. This didn’t surprise me, as online movements such as #selfcare have turned our collective yearning for rest and recreation into a commodity.

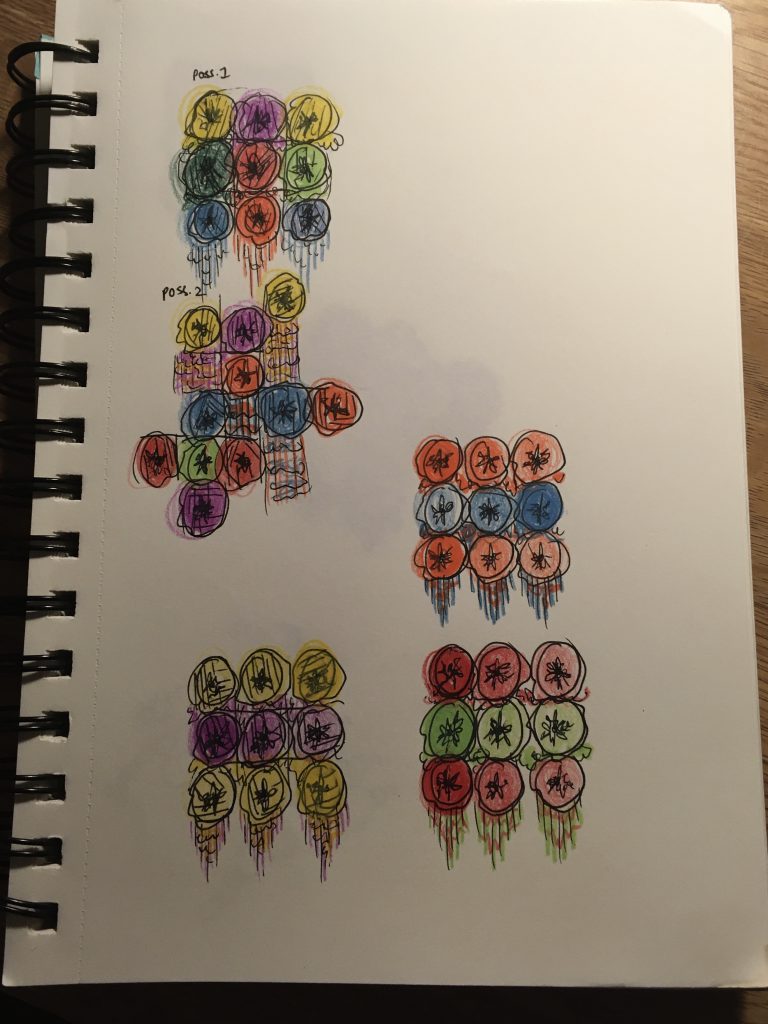

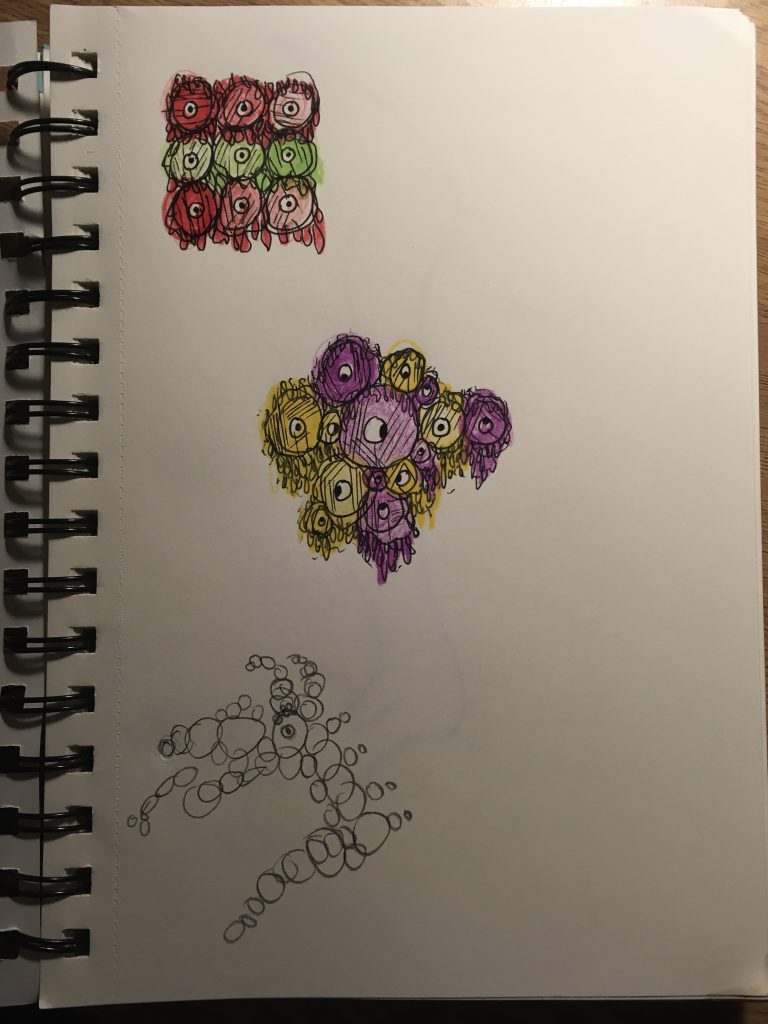

I decided that I wanted to try to avoid the polished, camera-appropriate aesthetic of joy behind as much as possible, and focus on creating a messy, imperfect piece of art that tapped into the delight and lack of inhibition of a child. I wanted to create a “vanity monster”—a storybook-like creature that faced the difficult task of remaining self-aware, silly, ostentatious, and humble all at once.

To stay in tune with the mischievous nature of my work, and to widen my audience, I decided to make my installation deconstructable and movable. I created a schedule for myself to have pieces of my “monster” up all over campus for no more than two or three hours at a time, both to make potential viewers question whether they really saw it or not, and to make it more difficult for security or SLC personnel to take them down.

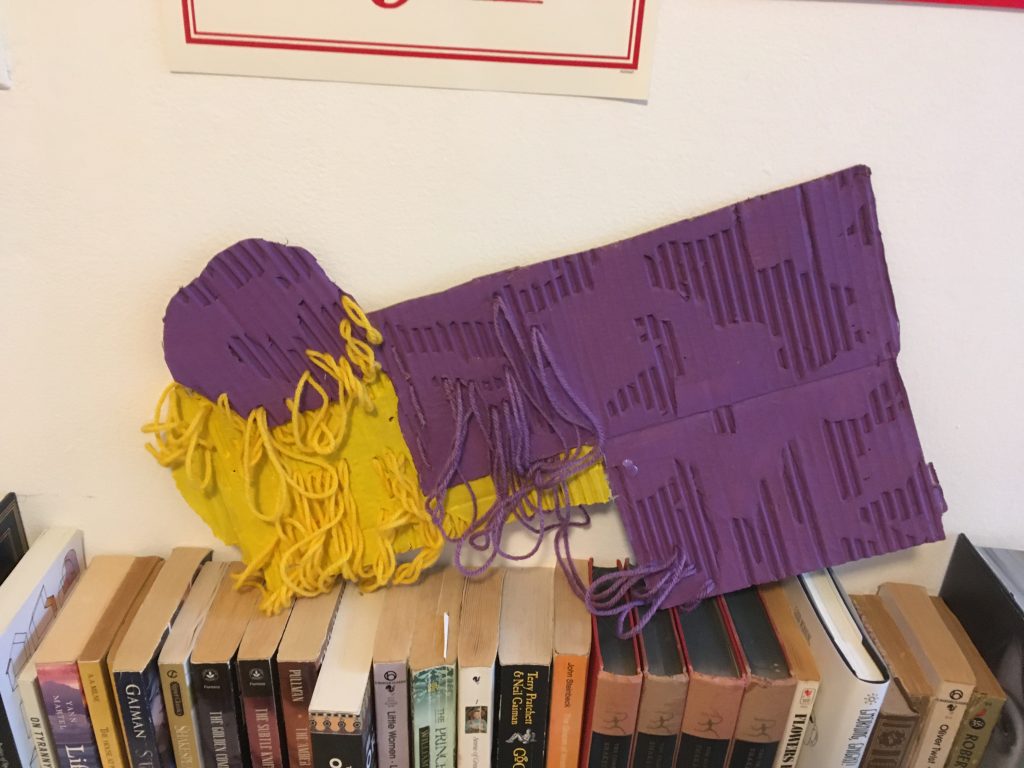

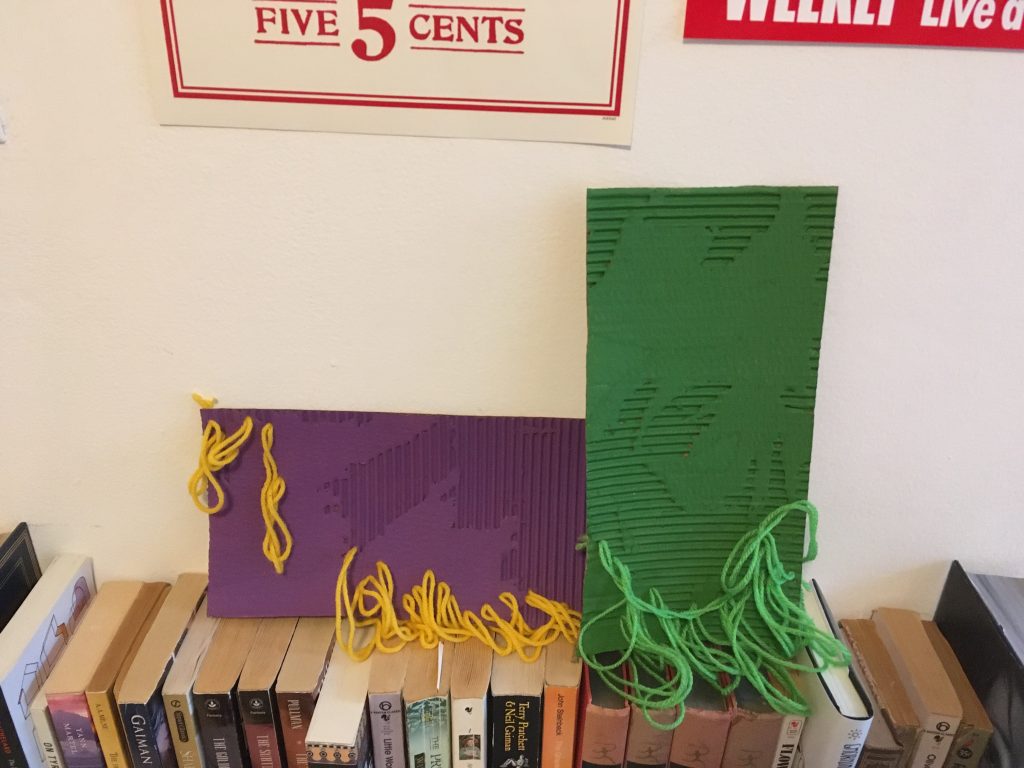

My project no longer felt like it needed to be a yarn bomb, nor was I confident in my ability to afford enough yarn/have enough time to cover my installation surface (two of the open metal railings on the second floor of Heimbold), so I incorporated painted cardboard for additional shape and texture. However, because I didn’t want to eschew yarn from my project altogether, I also delved into tapestry artists on Instagram (Natalie Miller, for example) who play with various yarn textures, to get a sense of how to create the “shagginess” of a monster.

After settling on a final design, I set to work—and instantly ran into the realization that I was chasing a pipe dream. Having had very little experience with creating large-scale art projects by myself (sets are usually built as part of a team), I had not realized that the monster I had envisioned would be so physically exhausting to build.

Finding myself running out of time, I downsized my project, keeping many of the major elements that had initially inspired me (joy, anti-Instagram aesthetic, childishness, humility) and instead of installing it on the rails of Heimbold, placing it onto my own body.

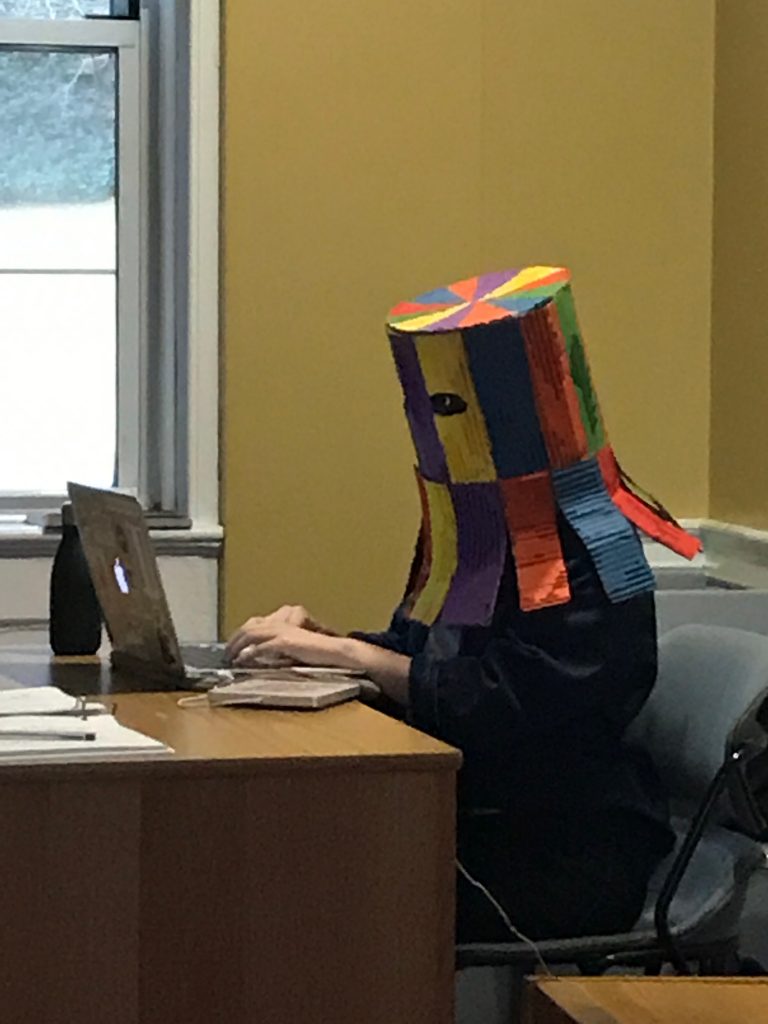

Thus was birthed the Former Vanity Monster, i.e. “I think I’m okay.”

The costume consisted of a mask (cardboard, wall paint, hot glue), belt (cardboard, wall paint, hot glue, yarn), and “gloves” (yarn). I constructed part of the mask out of painted elements that I had already planned to use for my vanity monster installation. I don’t exactly remember how the shape appeared in my brain, but I think I may have been influenced by children who play with cardboard boxes on their heads.

I planned to take this character, who I envisioned as a shy old-fashioned clown type, into everyday situations and see how many people I could surprise. Even though I did my best to create a joyful creature, I knew that my costume might not always cause joy. At this point, however, I felt I was after any unexpected emotions.

On Sunday, December 15, I put on a dress shirt, dark pants, and a tie (I was interested in the dichotomy of having an extremely childlike and silly character wear adult, “serious” clothing) and wore my costume at my desk job at the Marshall Field Music Building. This job requires that I ask students to sign in at the front desk, and often that I let in non-music students who don’t have swipe access to the building on weekends.

During my three-hour shift from 10am-1pm, I received double-takes, smiles, uncertainty about how to react, and tentative delight. I also received outright approval from two people (thumbs up, compliments) and some more exorbitant praise and otherwise extended reactions/conversations from people who knew who I was.

Performing in the costume, even though the mask restricted my vision, movement and breathing somewhat, I didn’t find it difficult to sit at a table and work (I did have good side-to-side line of vision due to the mask’s large eyeholes, and the mask didn’t affect my posture at all). I was interested in the fact that I constantly had impulses to smile while wearing the mask, and realizing that no one would be able to see. Consequently, I became more aware of my own body language as I adapted to having a more or less blank canvas for a face.

The same evening, I wore the exact same costume into Bronxville and waited at the train station for about 15 minutes until a train arrived. (I did not get on the train—that’s an experiment for a later date). As I was mostly mobile and could not pay attention myself, the person I had brought along to photograph me told me that I had received mostly double-takes and some stares. I also received my favorite unsolicited verbal opinion of the entire experiment: an oddly depreciatory “[It’s] not that strange.”

Another side effect of the mask, which I did not even think about when I designed this project, was that the anonymity felt very empowering. I am naturally shy and anxious in public places, and in Bronxville, I felt very little pressure to hold my face or body a certain way when confronted with a street patron. I also felt androgynous in a way that I never have before, in that my clothing and concealed face made it difficult to identify my gender. As a non-binary transmasculine individual who dresses androgynously but more or less appears biologically female, I was delighted to discover this alternate layer to my performance.

Overall, I’m not disappointed that I had to downsize my project, as I otherwise never would have discovered my penchant for masks. I would like to continue this pursuit, with different masks and in different locations—perhaps the next installment will take place over winter break, in my hometown of Monterey Bay, California.

Eventually, I would like to find some way to further amplify the core of the project, which started with joy and will end with joy. Beneath whatever mask I decide to put on my face, I want there to be a person whose only goal is to do good.

– Peck Trachsel