Almost every time I enter a grocery store, or a building with bathrooms, I am reminded of the persistence of the gender binary. There’s something dangerous about evidence of this kind——when it appears so inconspicuous, so innocuous, so “normal.”

[photos of tampons & pads]

I had a plan to create an art piece, or perhaps a series of art pieces, that used the very recognizable shape of a tampon to communicate a visual message: periods are not equivalent to gender.

For the message, I leaned into the simplest, most universal gender symbols that I hoped the majority of my viewers would recognize: the signs for male, female, and nonbinary, and the trans flag.

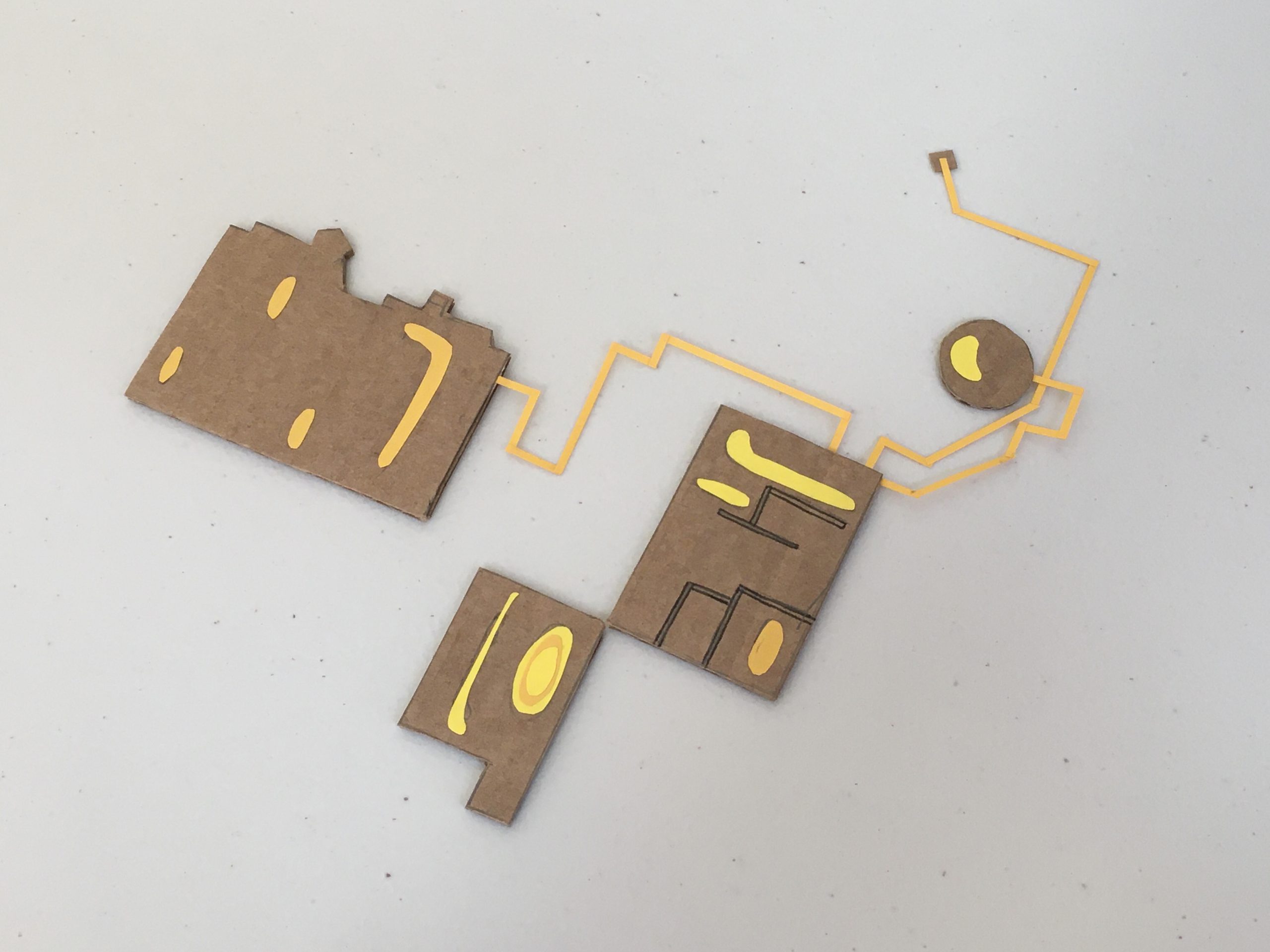

My first drafts experimented with what form my visual hijack would take: I created a few versions with line art, to see whether the best medium for my message was a single-panel comic. But I think I knew even then that working with real tampons would prove more successful.

[photos of first draft]

For my second draft, I bought a box of tampons and essentially created three-dimensional versions of my line drawings. Based on feedback from Angela and my peers that the artwork on its own carried a subtler message but a more powerful impact, I removed any explanatory text.

My in-class critique, as well as conversations with Angela, led me to add an additional element: a box of tampons, covered in white paper to create a blank canvas. I also wanted a semi-quantifiable method of engagement with the tampon box that didn’t just involve taking a tampon, as well as to add an additional layer of gender machination. I bought stickers, some of which looked traditionally “feminine” and some “masculine,” and wrote a N.B. asking engagers to take a tampon and add a sticker.

I installed the final version of my art pieces early Thursday afternoon: one in a downstairs all-gender bathroom at the Barbara Walters Campus Center, and one in each gendered downstairs bathroom in the Heimbold Visual Arts Center. I found the process nerve-wracking, not necessarily because I was worried about installing an art exhibit with a somewhat controversially progressive message, but because the installation took a minute to put up and I wanted to remain anonymous. I checked all my pieces after two days, and found that the BWCC installation had been removed entirely——first the artwork, then (after I checked a second time) the tampon box, along with all its stickers.

I have checked engagement with my Heimbold installations by counting the remaining tampons and pads left, as well as how many stickers are on the box. The women’s restroom has a more equal stickers—to—missing tampons ratio, whereas the men’s has tampons missing but very few stickers.

I am not social-media fluent, so I enlisted a couple of close friends to keep an eye out for any online mention of my installation. The BWCC version inspired some posthumous, but positive commentary:

[photos]

…and one of my classmates, Sarah Morse, also overheard a piece of conversation spreading news about my BWCC installation.

As of now, my Heimbold installations are still up. In the women’s restroom, the tampons and pads are all gone, while in the men’s, the box is still mostly full.

The stickers on the box in the women’s restroom are pretty evenly split (visually, at least) between the “masculine” and “feminine” stickers——there may be more “feminine” stickers, but only because as a whole they were smaller. They are also very evenly placed, and there are fewer stickers than there were tampons, as though to maintain the integrity of the design created by the many bathroom/tampon users over the course of the project.

Throughout the week of installation, I wished I could find out how many people engaged with the actual art piece as opposed to the tampon box, but regardless, I am pleased with my project’s ability to engage with a selection of SLC’s population and provide a service that most period-havers agree has an unfair price tag.