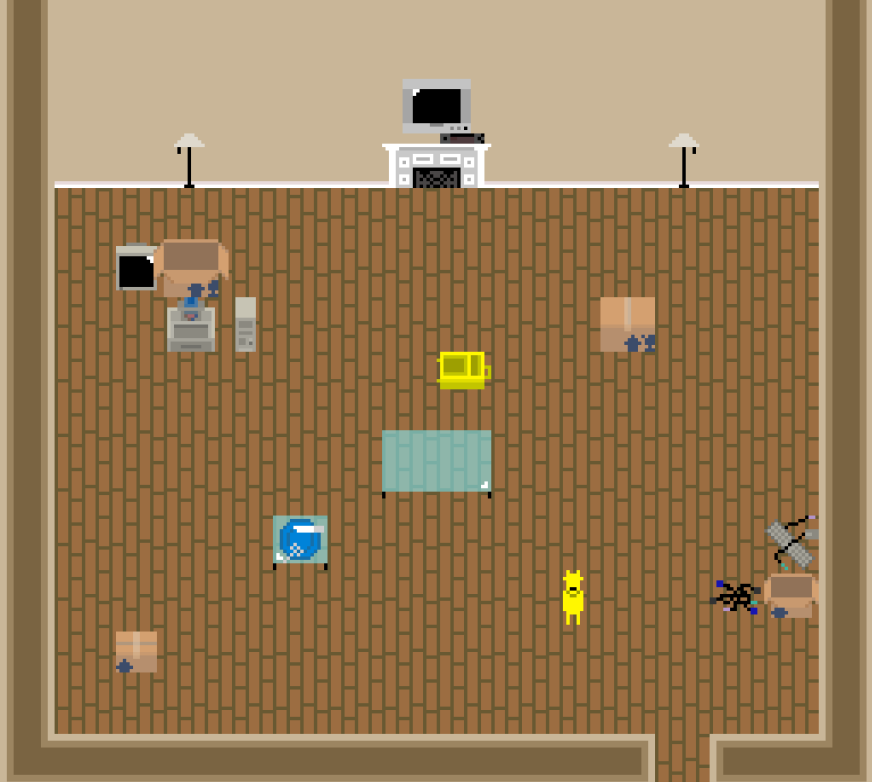

The elevator pitch for “Borrowing” goes something like: you play as a little yellow man who is moving into a home in the suburbs that’s way too big for just himself. By unpacking, you take part in the yellow man’s kleptomaniac tendencies, uncover his peculiar obsession with particular pieces of popular art, and learn a little about his past. It aims for a balance between dry, sardonic humor and a Twilight Zone-esque sense of unease.

The elevator pitch for “Borrowing” goes something like: you play as a little yellow man who is moving into a home in the suburbs that’s way too big for just himself. By unpacking, you take part in the yellow man’s kleptomaniac tendencies, uncover his peculiar obsession with particular pieces of popular art, and learn a little about his past. It aims for a balance between dry, sardonic humor and a Twilight Zone-esque sense of unease.

Ultimately the game is about plagiarism and was inspired by a moment where I was publicly accused of stealing the plot of a famous film for a short story. In designing a game where you control a man who habitually misconstrues and rationalizes stealing for borrowing, the point isn’t necessarily for the player to feel sympathy for the yellow man so much as believe that stealing is the correct way to progress and therefore be complicit in his actions. In a fully completed version of the game, it’s conceivable that there might be multiple end states: one in which you’ve fully unpacked and furnished the house with things that aren’t yours and get caught; and a second where you’ve fully unpacked without taking anything at all, with the game’s design hopefully leading the player naturally towards the former on a first playthrough. The game has its roots mostly in the mechanic-as-metaphor styled abstraction seen in Jason Rohrer’s Passage, perhaps with a bit of the inquisitive exploration of molleindustria’s Every Day the Same Dream.

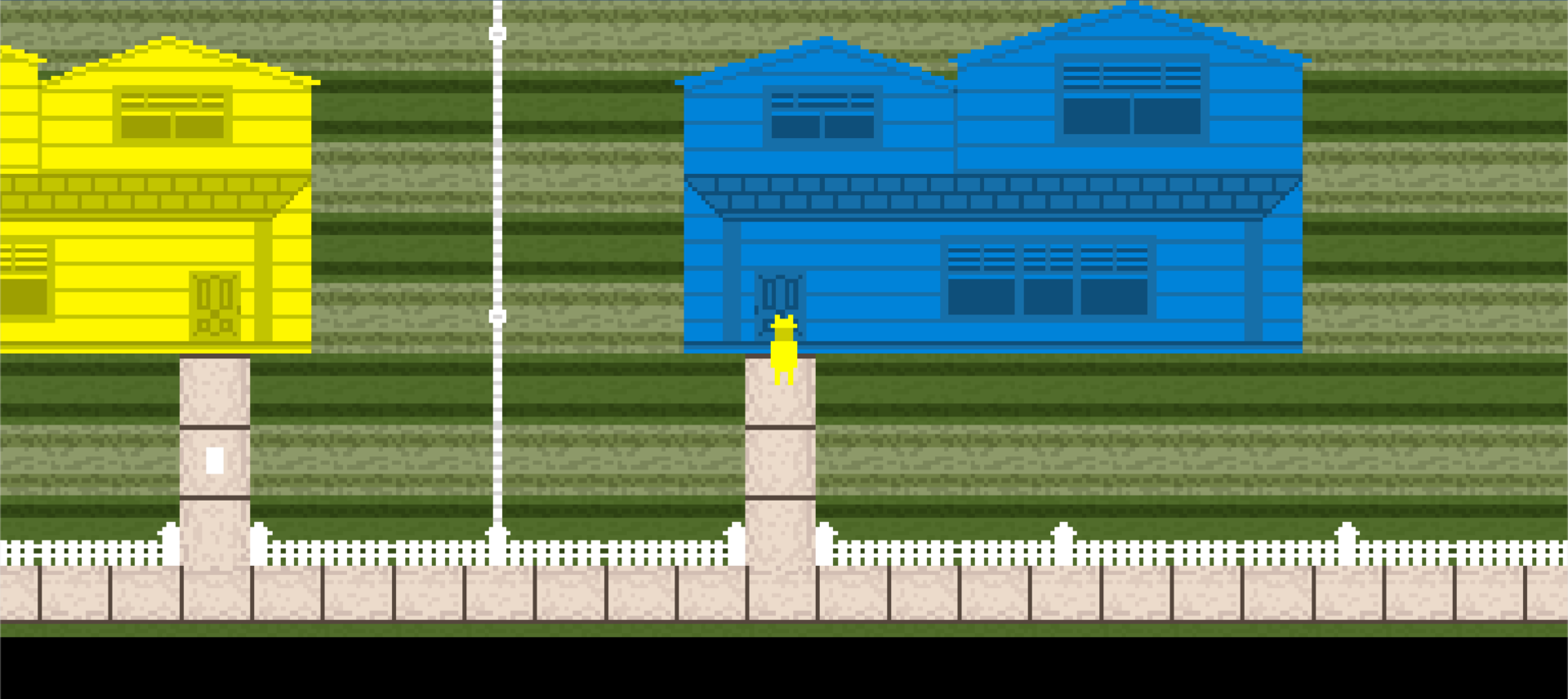

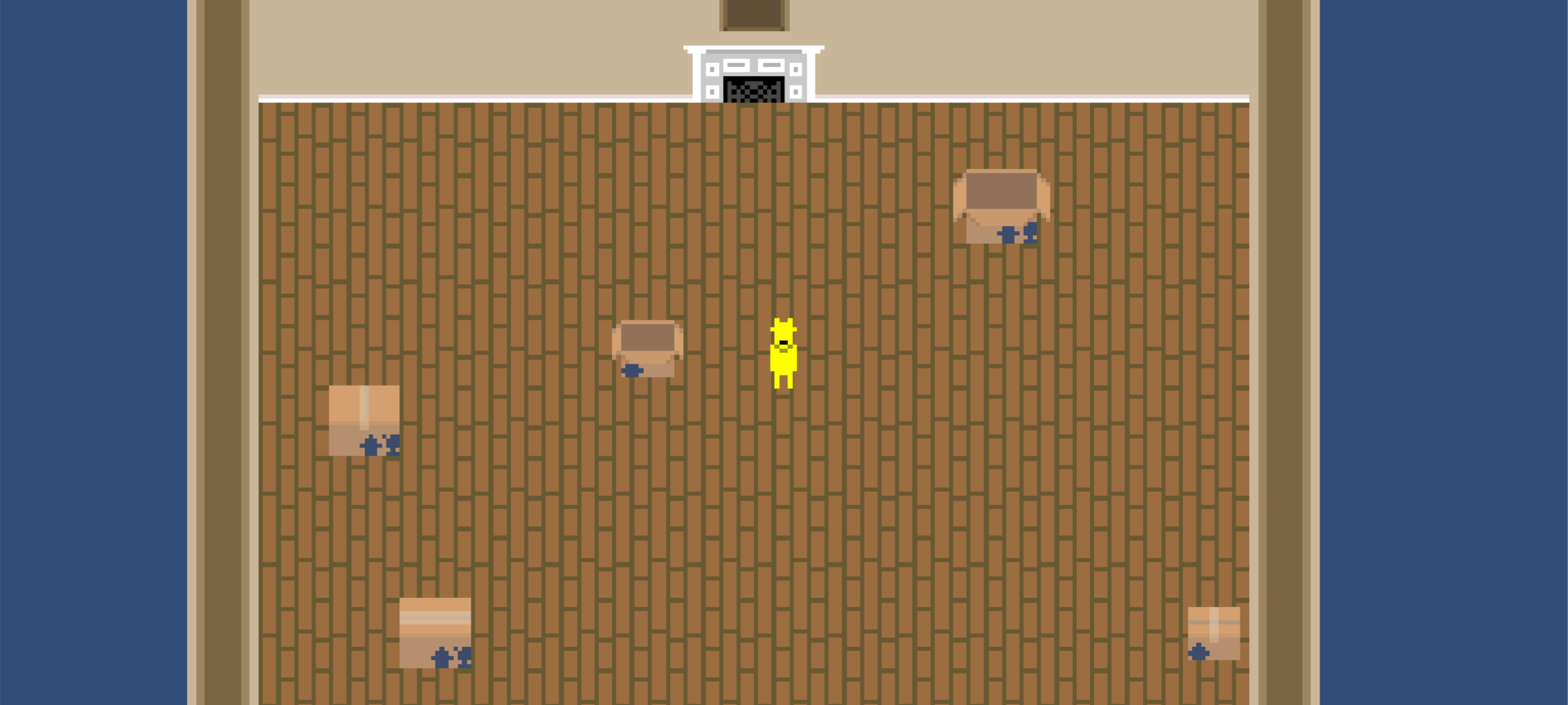

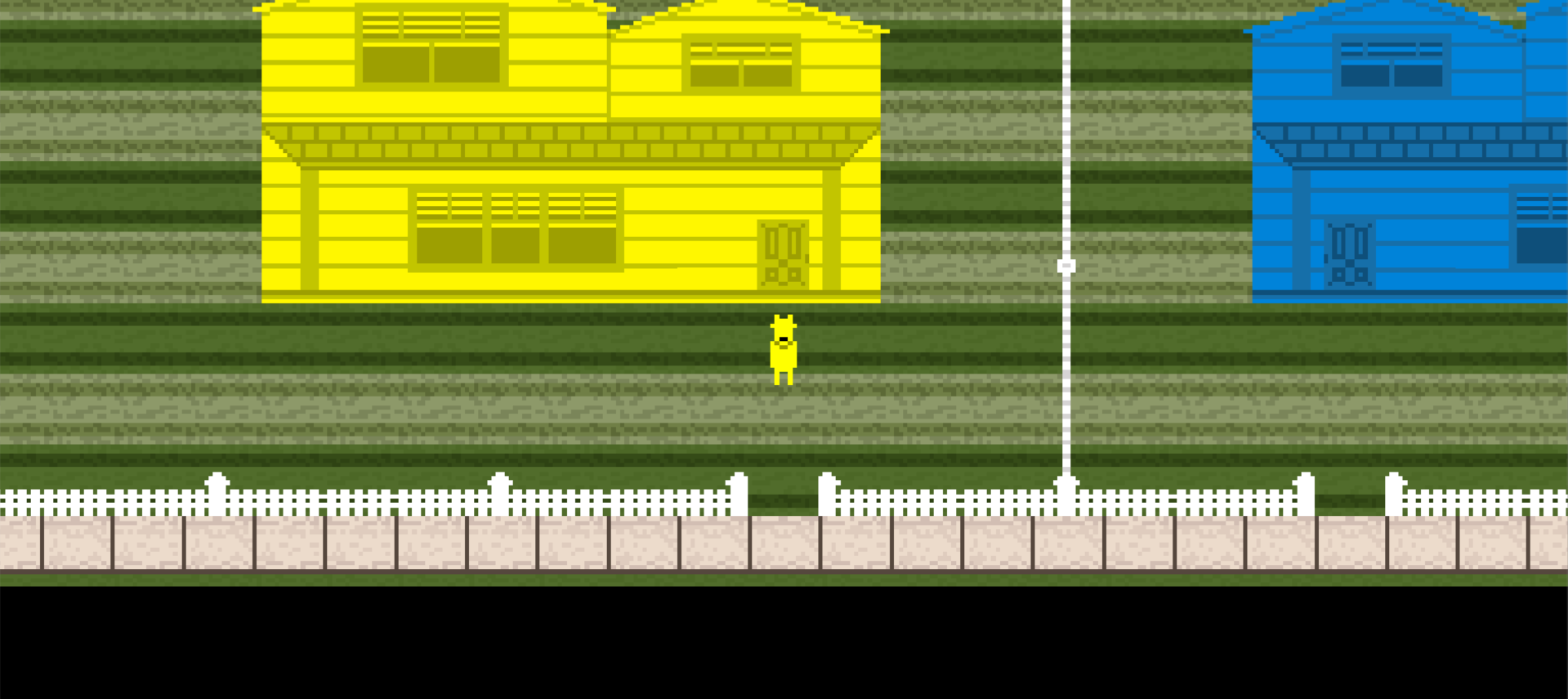

The original intention for the aesthetic of “Borrowing” was to be reminiscent of old-school Atari games. I wanted to challenge myself by using a very limited amount of colors for each sprite, relying on the shape of each object to convey what it was more than its texture and detail. I feel I’ve accomplished this in some ways – the two houses, for example, are limited to four shades of yellow or blue each and have no heavy detailing – reached mixed results with others – the yellow man himself and the home interiors in particular – and completely abandoned this idea in others, as with the lawns and sidewalk. I still find myself a bit more attracted to the low detail aesthetic and would hope to continue it as more art is made. There may be something to be said about a “blander”, more empty world that uses swaths of color to define itself rather than a richly detailed one. Perhaps the yellow man, dull and unoriginal as he is, sees the world this way and so is shocked (and maybe the player is, too) when he sees the richly furnished insides of the blue house contrasting so starkly with the greater suburbs and his own home, but I feel that’s something of a stretch.

The original intention for the aesthetic of “Borrowing” was to be reminiscent of old-school Atari games. I wanted to challenge myself by using a very limited amount of colors for each sprite, relying on the shape of each object to convey what it was more than its texture and detail. I feel I’ve accomplished this in some ways – the two houses, for example, are limited to four shades of yellow or blue each and have no heavy detailing – reached mixed results with others – the yellow man himself and the home interiors in particular – and completely abandoned this idea in others, as with the lawns and sidewalk. I still find myself a bit more attracted to the low detail aesthetic and would hope to continue it as more art is made. There may be something to be said about a “blander”, more empty world that uses swaths of color to define itself rather than a richly detailed one. Perhaps the yellow man, dull and unoriginal as he is, sees the world this way and so is shocked (and maybe the player is, too) when he sees the richly furnished insides of the blue house contrasting so starkly with the greater suburbs and his own home, but I feel that’s something of a stretch.

State of the Game was based mostly on aesthetic development and focused in on the outdoor environment and the yellow man’s design. While I agree that the more detailed sprites for the exterior were more pleasing than the simpler ones (the solid green lawn sprites in particular hurt my eyes when the character moved), I’m still interested in finding some kind of compromise between the more highly detailed sprites that are used now and the less detailed work that’s found elsewhere in the game. Comments on the yellow man I found particularly helpful and amusing, and it was in his design that I saw the biggest drawback of attempting to adopt an Atari-like style. Though many thoughts tended more or less towards what I had intended for him – an average Joe, busy businessman kind of look – the simplicity of his design and restrictive use of color legitimately can make his hat look like horns and possibly does give him a more shady, sinister look. I was specifically fascinated by the latter, especially knowing what I wanted him to do in the game. He stands as he did during the State of the Game for now, but I’m not opposed to redesigning him in any way.

Going into the paper game, I was interested in seeing how it was possible to encourage the player to steal more than just the initial item required to open the boxes. I was pleasantly surprised to hear that some classmates’ first thoughts were to steal the items in the blue house, though I would hesitate to believe that that inclination was a direct result of the game, its design, or even the player’s/observers’ “gaming instinct” so much as the fact that it was readily observable in the paper models that each piece of furniture existed on its own and was therefore collectible rather than being drawn into the environment and inaccessible. The way I had originally thought to encourage the player to steal furniture from the blue house was for them to finish unpacking a box, then revealing a text prompt from the yellow man to go into the neighbor’s home and steal the corresponding piece of furniture i.e. by unpacking the box with books in it, the yellow man would indicate that he wants a bookshelf. This design does not account for a player who is disinterested in completely unpacking a particular box (the prompt from the yellow man was technically never reached, though I allowed the stealing mechanic to be unlocked and take effect anyway) and could be solved simply by having less objects in them if I wanted to keep this kind of design. The actual contents of the boxes are more or less obscure depending on how much background knowledge the player has about historical examples of actual and alleged plagiarism, and that’s something I’m willing to embrace, though having some kind of flavor note that tells the player that the yellow man is collecting pieces of supposedly plagiarized art would definitely be a plus. I was happy to see that the found flavor notes and plot hook items were capitalized on by the player (albeit at the encouragement of the observers) and the given connections between the notes and theme of the game were apparent. In a case where the player found more of these (again, probably a fault on my part from putting too many objects in each box), I feel that the theme of the game would have soon become apparent.

Going into the paper game, I was interested in seeing how it was possible to encourage the player to steal more than just the initial item required to open the boxes. I was pleasantly surprised to hear that some classmates’ first thoughts were to steal the items in the blue house, though I would hesitate to believe that that inclination was a direct result of the game, its design, or even the player’s/observers’ “gaming instinct” so much as the fact that it was readily observable in the paper models that each piece of furniture existed on its own and was therefore collectible rather than being drawn into the environment and inaccessible. The way I had originally thought to encourage the player to steal furniture from the blue house was for them to finish unpacking a box, then revealing a text prompt from the yellow man to go into the neighbor’s home and steal the corresponding piece of furniture i.e. by unpacking the box with books in it, the yellow man would indicate that he wants a bookshelf. This design does not account for a player who is disinterested in completely unpacking a particular box (the prompt from the yellow man was technically never reached, though I allowed the stealing mechanic to be unlocked and take effect anyway) and could be solved simply by having less objects in them if I wanted to keep this kind of design. The actual contents of the boxes are more or less obscure depending on how much background knowledge the player has about historical examples of actual and alleged plagiarism, and that’s something I’m willing to embrace, though having some kind of flavor note that tells the player that the yellow man is collecting pieces of supposedly plagiarized art would definitely be a plus. I was happy to see that the found flavor notes and plot hook items were capitalized on by the player (albeit at the encouragement of the observers) and the given connections between the notes and theme of the game were apparent. In a case where the player found more of these (again, probably a fault on my part from putting too many objects in each box), I feel that the theme of the game would have soon become apparent.

In general, development is coming along quite nicely so far. The initial tilesets for both the interior and exterior areas of the game are entirely completed, and spritework has moved on to boxes, furnishings that can be borrowed, and the items that are unpacked. At a continuous, casual rate, I can see the majority, if not all, of the initial spritework completed sometime between a week and a week and a half. From there work on the code for picking up and placing down movable objects would commence, and I would be content to meet that milestone by the end of the semester.