Statement: A visual hijack is when an artist uses the visual strategies of an oppressive image, or target, to re-establish new ideas that are counter or detrimental to the system that the oppressive image upholds.

Part 1: Setup

-

-

- Choosing Target

- Choosing a target requires a target that is not only choose-able but workable. There are many images and visuals that are oppressive to people, but a good target is one that is both flexible to change and iconic enough that this idea-override will be a challenge.

- For this hijack, I chose Breitbart. Breitbart is a very popular and inflammatory conservative news company run in the United States, born from Andrew Breitbart, a former journalist at the Drudge Report (Phelan, 2016). It is perhaps the face of conservative news in the US and is extremely well-known by name and persona.

- What Makes Breitbart a Good Target

- Much of their content is, definitively, oppressive to the artist.

- Follows Daniel Dennett’s Rules for Evolution (Dennett, 127) (and therefore, something that will stick around)

- Choosing Target

-

“Heredity or replication” (Dennett, 127)

Breitbart is a very successful replicator, meaning that its single form (Breitbart news story) is both easily repeated not just in craft, but in idea and memory. There is something that sticks in one’s brain and the brain of others (Dennett, 129) to reaffirm the idea of Breitbart as a creator of conservative news. Their consistent updating also reminds us of this.

The name and persona of Breitbart extend beyond the news story. If one were to say, Breitbart is going to be at the rally!, one would not presume a series of newspapers to stand up and speak. The company is an idea beyond its own function, and that idea is replicated both by its function and the function of other people.

“Variation” or “an abundance of elements” (Dennett, 127)

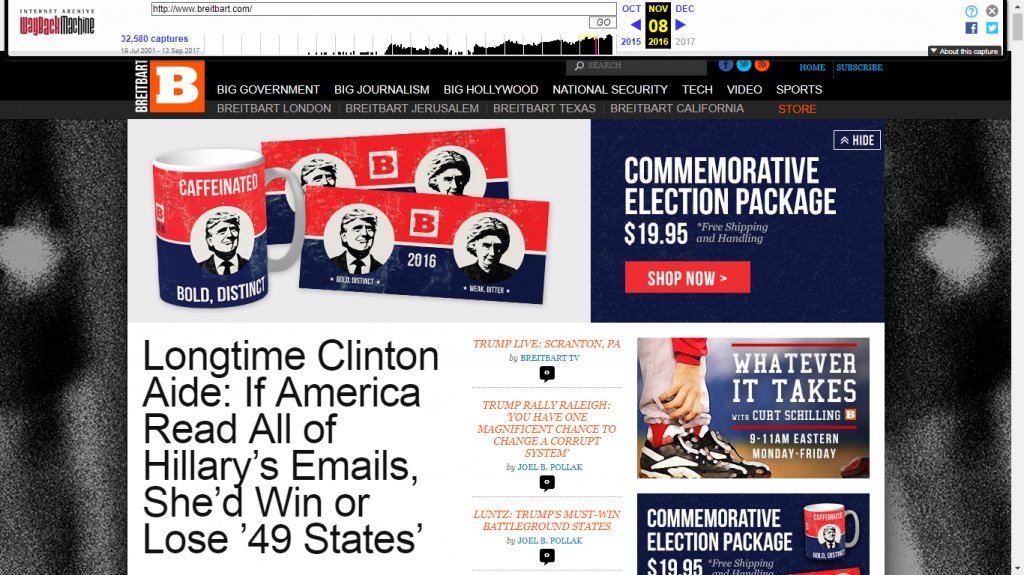

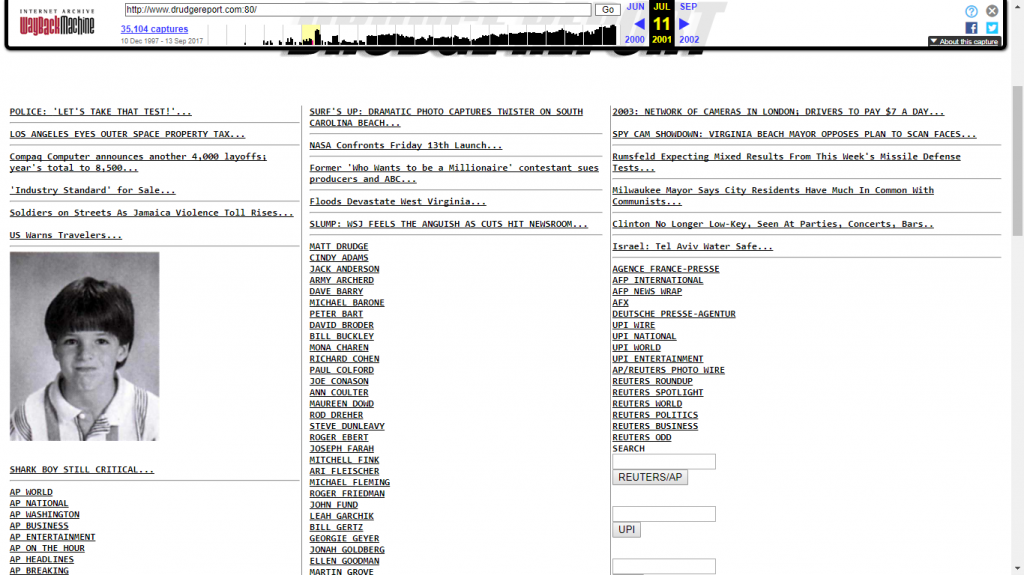

The elements in this project included the design of Breitbart, a screen capture from Breitbart the day after the election of the 45th president of the United States (Wayback, 2016), and a screen capture of The Drudge Report on July 11th, 2001, the closest pre-9/11 capture available (Wayback, 2001).

Breitbart has many words on its page, being a news company. Many of these words are topical buzzwords and naturally have their own ideas and feelings attached to them.

For this project, I also used language from the Drudge Report, Breitbart’s predecessor, to increase the elements available. Drudge Report, pre-9/11, has a lot of pre-contemporary language and distinct linguistic catches that look jarring beside the more typical contemporary ones.

“Differential ‘fitness’” (Dennett, 127)

Breitbart produces several articles with repetitive buzzwords to create a public reaction to an idea, using the same model of “fitness” (Dennett, 127). By recreating the same elements in varying orders with different emphasis, Breitbart employs the same system as most memes to create ‘new’ content.

Therefore, the elements in Breitbart writing as well as Drudge Report headlines are already packaged and ready for remix. Using large or small quotes from the sites creates levels of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ within the paper, by splicing common ideas and repairing them with a Frankenstenian sense of culture. When placed together as a cohesive piece, it is difficult to establish one clear reality.

-

-

- Defining Working Systems

- Breitbart, as a news source, is very popular: why?

– Gramsci suggests that there are two kinds of “intellectuals” (Gramsci 113), those who are naturally “organizers” (ibid) and “organically” (ibid) rise to lead people, and those who “[emerge] into history out of the preceding […] structure” (Gramsci 114).

– Breitbart, ironically, is the latter spinning itself to seem the former. Unlike the classic bootstrap American narrative, Breitbart did not rise from the American public just as conservatives needed it, but was an egg waiting to hatch for many years.

– Andrew Breitbart left The Drudge Report in 2005 to begin Breitbart Media (Phelan, 2016). Gaining popularity from its predecessor and from Breitbart’s reputation as a catchy journalist for Drudge Report, the news source became a household name after getting famous with their report Big Government in 2009 (Phelan, 2016). - But why was their internet popularity so fast and effective?

– Ken Layne says about Andrew Breitbart’s reporting style at Drudge Report, “just choosing links and writing a great headline and placing it on the page — is a real art form” (Phelan, 2016).

– Mark Dery, a web scholar, writes that the “one-liner” is an intensely effective online format (Dery, 2).

– Breitbart gained popularity because it was easy to read and was a “unique brand of lightweight, gossamer junk” (Phelan, 2016) while attacking “intellectual scaffolding” (ibid).

– The same short form use of repetitive, easy to understand elements in different positions allowed for Breitbart to become one of the most iconic conservative news sources of our time. By not requiring much attention but having a high malleability, Breitbart was allowed to produce and reproduce easily.

– This success gives it authority, and the authority mixed with replication causes it to “‘produce’ intellectuals” (Gramsci, 117) who, in turn, give it authority. - How do you hijack this?

– When online, there is a sort of anonymity; personas are built on digital footprint rather than their identity. “People are judged on the content of what they say,” (Dery, 2) and who they are comes from that action.

> Use the Breitbart name and likeness to create and alternate persona that reflects a facet of why it is oppressive

– There are three key components to target for Breitbart: its replicability, its notoriety, and its credibility. Although I could have done a project on how the articles describe Dennett’s fitness, or a project showing the hypocrisy of promoting fringe news from a singular large company, I chose to attack the credibility.

- Breitbart, as a news source, is very popular: why?

- Defining Working Systems

-

-

-

- What defines the hijack?

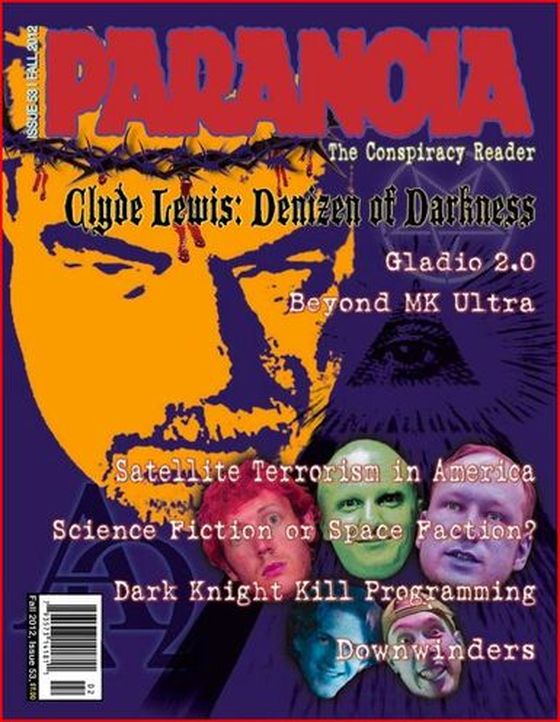

– For publications that were notoriously unreliable, my initial idea was simple headlines with incorrect photos. However, this evolved into a more distinguished metaphor: using the conspiracy magazine.

– Conspiracy magazines are known for false, outlandish, and usually fabricated information. This seemed like the perfect reflection of the ‘fake news’ phenomenon. It also enabled me to use the integrity of the Breitbart name against them.

– The same brevity of headline and buzzword tactic is used in both conspiracy magazines and the Breitbart articles, but how they are judged is different. The artifice is similar, but the value is different because of reputation.

– Like a news company, the magazine implies replication (multiple issues). This metaphor helps to uphold the same replicative property as Breitbart, the news company.

– Because I was attacking the credibility of Breitbart, I made an active effort to use its other two major strategies in my favor, so that my piece would appear more connected to my target.

- What defines the hijack?

-

- Magazine Building

- First Prototype

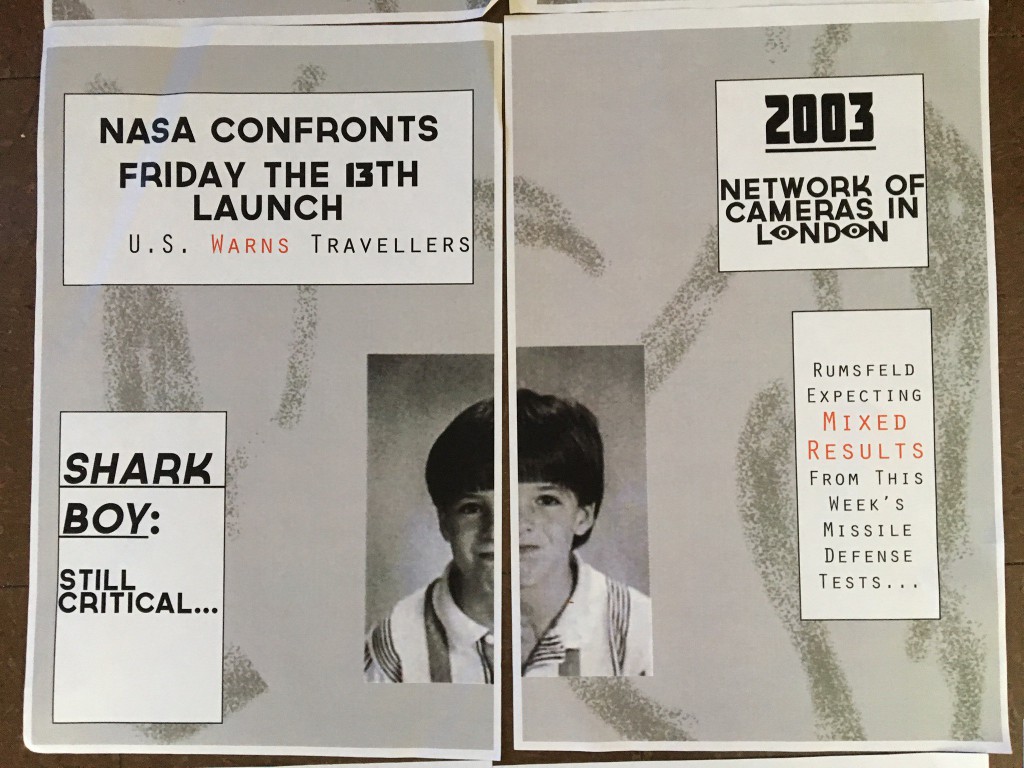

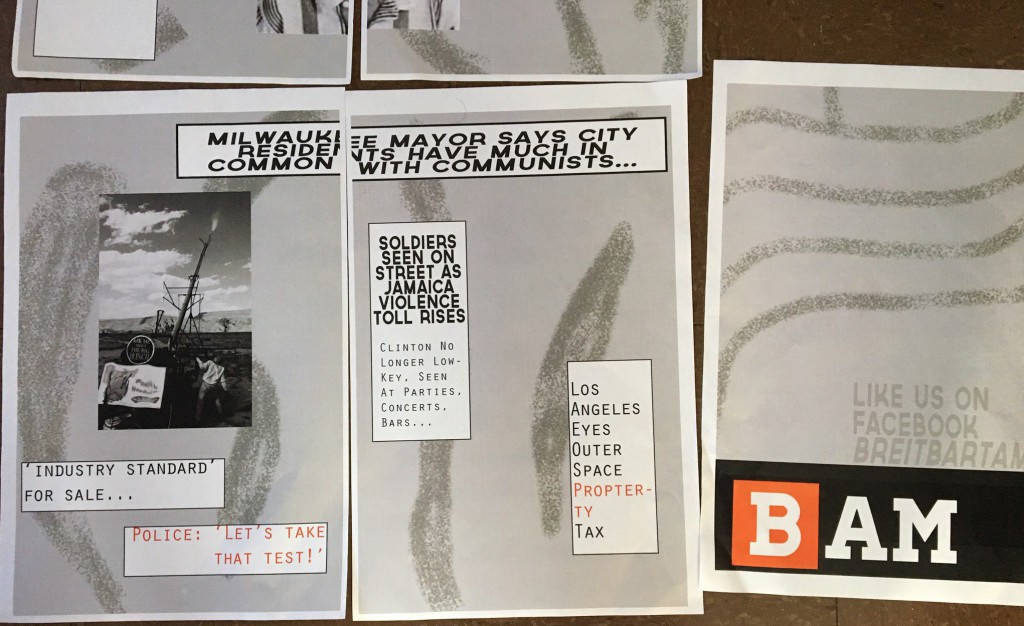

– Most of the work for the magazine occurred in Adobe InDesign. I used Photoshop to create backgrounds for the magazine, mimicking the spray paint design of Breitbart’s official website. The three focal colors (orange, gray, and black) were taken directly from screenshots of the website. Not having worked in InDesign prior, this was quite the adventure, but the program proved to be more friendly than unfriendly!

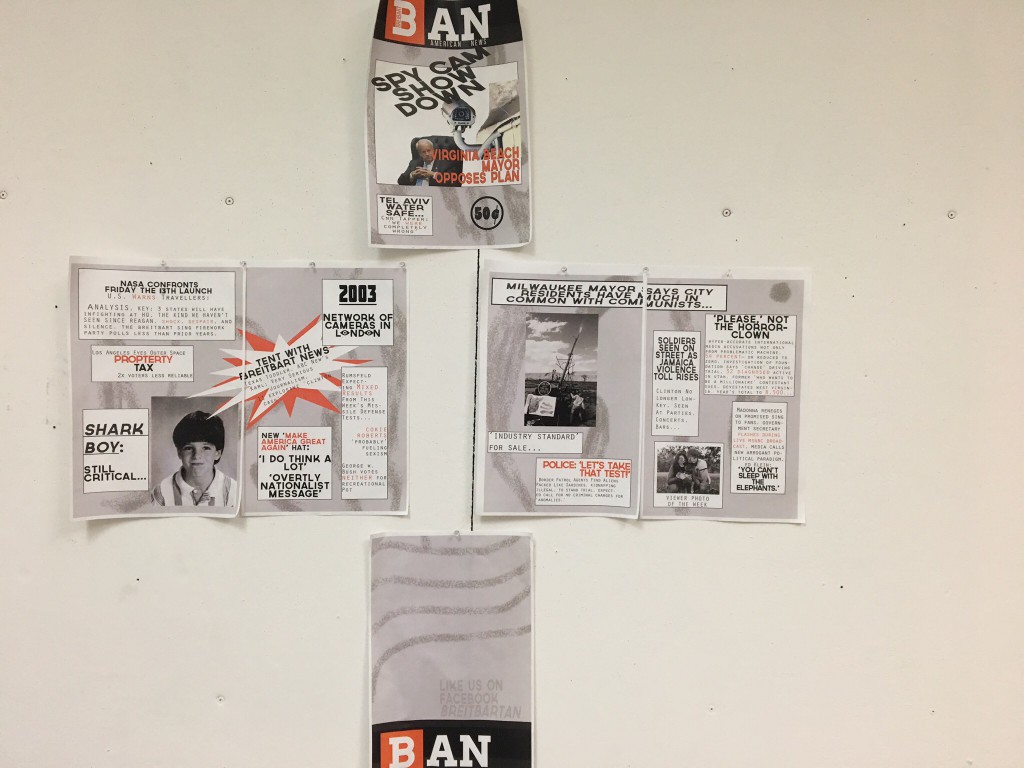

– I deeply wanted the newspaper to be large and unruly when read, so the paper size was 11×17 inches. This proved correctly impossible to handle when printed.

– Before designing the layout of the piece, I compiled several references for ‘old’ conspiracy magazines covers. Paranoia proved both the easiest to find and the best representation of a variety of covers, featuring image- and text-heavy covers. I then emulated the closely-oriented/busy layout of the covers, which felt surprisingly easy and natural.

– Most limitations were in the composition of the magazine format, but the metaphor of a conspiracy magazine was a fun and easily mimicable. The limits guided the piece more than restricted it.

– My original goals for this prototype were to play with the ideas of headlines from Drudge Report only, with images from public web using keywords from headlines, using only the design from the Breitbart website.

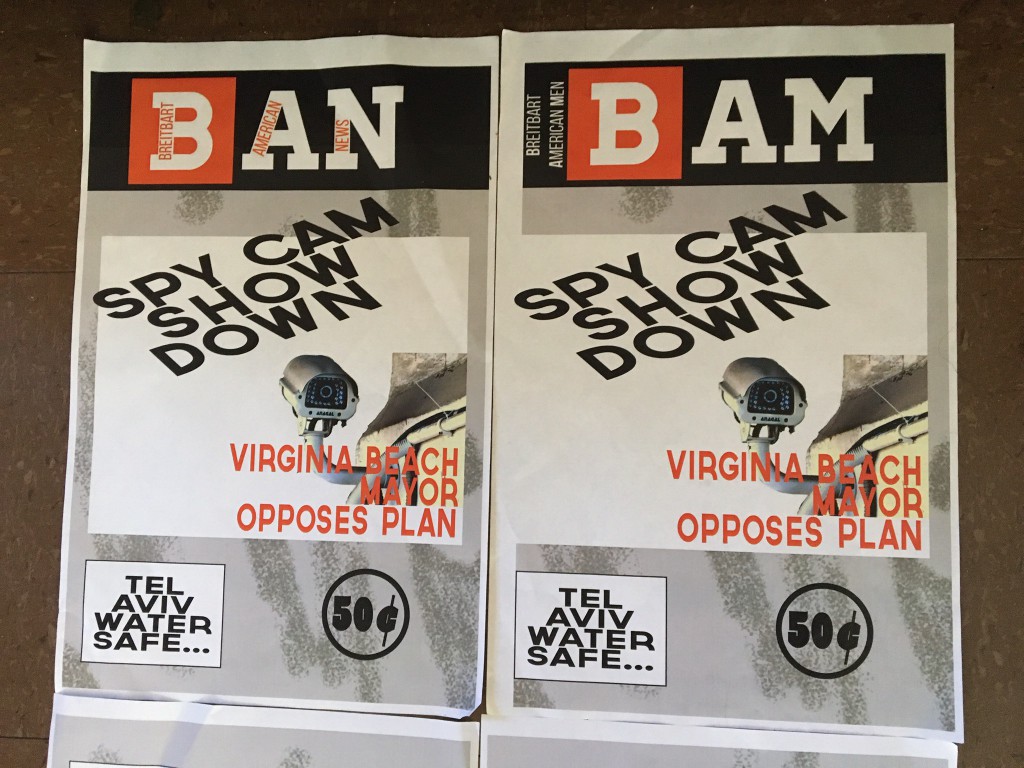

– Titles for the magazine varied, trying to describe the fake authorship; options were: Breitbart American Men, Breitbart American News, and Breitbart News.

- First Prototype

2. Second Prototype

– The second prototype was modified to include more text: it now included Breitbart’s contemporary headlines. This lead to more dense text and smaller ‘packets’ of words and phrases for use, in order to disguise the headlines. The newer words allowed also for more play and topical humor, which felt easily accessible

– There were also more images, to allow for a more gentle visual experience. The title that I settled on was BAN: Breitbart American News

– Lastly, this week I finally created the BreitbartAN Facebook page which is listed on the back of the magazine, and which only has posted the screen captures of the Breitbart and Drudge Report websites.

-

- Third Prototype/Final

– The third prototype had more focus on ‘public’ interaction: I added ‘viewer of the week’ photo, a mail in portion of the magazine, and the Facebook icon that is recognizable on so many websites today. These changes work with helping the magazine to appear connected and “making the world a little smaller,” (Fairey, 3).

– Again, the design was altered to make the piece more legible and move better across the page. There were plenty of other design notes after this prototype, however, they did not make the final for time issues. Still, it shows that rarely is any design perfect!

- Third Prototype/Final

For Access: PROTO EDIT

- Installation

- The Inaugural Year: Celebrate Sarah Lawrence

– The purpose of this event, according to the Sarah Lawrence website, was to “highlight dance, music, theatre, and writing performances and readings; science demonstrations and posters; displays by student visual artists; Sarah Lawrence programs beyond the campus; Graduate Programs; student publications; dessert reception and the opportunity to have your photo taken with our college mascot, Godric the Gyphon” (Sarah Lawrence, 2017).

– The event itself was spread throughout the first two floors of the Heimbold Visual Arts Center and several outdoor staging areas.

– Many alumna, board members, and donors were present as well as students to blend in with. I chose this event because not only did is present a group who was not typical to the college, but it also presented a group who was a risk for the college to interact with. These people also likely had a knowledge of what Breitbart was, and perhaps might even have an opinion on the piece. - Distribution

– Originally, I planned to wait at a singular table and distribute 15 printed copies of the magazine as a repeated action; however, due to how few people were in the area, I began to move throughout the event spaces and hand out papers.

– A friend and photographer, Khalifah Jamison, took photos of people reading the magazine and of myself handing them out.

– Surprisingly, it was very hard to wait for people to take the magazine. This was remedied with a much easier “would you like a newspaper”/”would you like a magazine.” - Gallery

– At one point, I entered Barbara Walter’s Gallery. At the suggestion of Jamison, I stood in middle of an exhibit portion so that it appeared I was there as a part of the exhibit. Many people saw me enter the gallery, however, many more did not.

– I passed out several newspapers within the gallery, this time without speaking or with as few words as possible. Many people took the time to very much study and read the paper, some even looking at the art behind me for answers. Several groups of people read the paper and returned it, thinking that it was a permanent part of the exhibit. - Reactions

– Most people received the magazine with confusion. Twice, people laughed. One person rejected the magazine upon seeing the Breitbart name, but their companion took the paper.

– A few people held onto the magazine, more people secretively than visibly. This leads me to believe that although they may have wanted to read it, they were ashamed of the Breitbart name. However, there were some who openly displayed the Breitbart logo as they carried it.

- The Inaugural Year: Celebrate Sarah Lawrence

– The only people who carried it visibly, from who I noticed, were white men.

- Conclusions

- Did This Work

– I think so; many of the people who talked to me about the magazine asked questions such as “who did this?” and “is this real?”

– The purpose was to destabilize the view of ‘credibility’ of Breitbart name and source. By making people unsure about whether Breitbart had actually published a nonsense conspiracy magazine, I feel accomplished and that my ideas translated correctly. - SURPRISINGLY, the Facebook page backfired.

– The Facebook page has had a surprising amount of interaction, but it does not seem to be anyone related to Sarah Lawrence College or from Yonkers/Bronxville area. There was one person who interacted with the page from Yonkers.

– The page has been tagged in links to an actual Breitbart article.

– The page has been sent message about a conservative activist in trouble. - The messages replicated differently online versus with the magazine.

– The Facebook page only had the untouched content from the Drudge Report and Breitbart, meaning that there was no hijack necessarily present. Therefore, posting it online without the finished product meant that it only replicated the Breitbart name and likeness without the critique of the final product. This was not only unintentional, but a failure to consistently represent the product cross-platform.

– In this case, the Breitbart name outshone the content itself and proved too strong to feasibly hijack, and in fact hijacked the project itself. - Although the credibility of Breitbart was put into question by this piece, the reach was small due to the print nature and the institution of Breitbart remains mostly unaffected.

- Did This Work

- Future work

- I would like to use the growing (?) online basis to replicate the short form conspiracy publication, but instead as a consistently published online publication. This would require continuing to find new elements from Breitbart and Drudge Report as well as choosing the set for these elements (ie. parameters for what screen grabs to use).

- An alternative to creating my own conspiracy work would be to use the same growing online basis to link to screenshots of actual conspiracy news websites. Again, the Breitbart name and image have proven very strong within this project, and the continual use of this header would stand as the backbone and reference for this project.

- Lastly, perhaps the best thing to do is re-research more forms of working on removing credit from organizations or change my perspective on this project entirely. The first way is not necessarily the best way, and more reading and viewing cannot hurt!

End Notes

“The Inaugural Year: Celebrate Sarah Lawrence.” Sarah Lawrence College. Accessed October 16, 2017. https://www.sarahlawrence.edu/news-events/events/2017-2018/2017-10-05-inaugural_event_cele-eid217579.html.

“DRUDGE REPORT.” Wayback Machine. July 11, 2001. Accessed October 16, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20010711064315/http://www.drudgereport.com:80/.

Dennett, Daniel C. “Memes and the Exploitation of Imagination.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 48, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 127-35. Accessed October 15, 2017. doi:10.2307/430902.

Dery, Mark. Flame Wars: Discovery of Cyberculture. Durham and London, UK: Duke University Press, 1994.

Fairey, Shepard. “Sticker Art.” Obey Giant. May 2003. Accessed October 16, 2017. https://obeygiant.com/essays/sticker-art/.

Gramsci, Antonio. “Antonio Gramsci.” In AN ANTHOLOGY OF WESTERN MARXISM, edited by Roger Gottlieb, 112-19. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Nussbaum, Daniel, Joel B. Pollak, Jeff Pooro, and Neil Munro. “Breitbart News Network.” Wayback Machine. November 08, 2016. Accessed October 18, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20161108073830/http://www.breitbart.com/.

Phelan, Matthew. “Building the House of Breitbart.” Jacobin Magazine. November 05, 2016. Accessed October 15, 2017. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/11/breitbart-news-drudge-alt-right-koch-trump/.

![Cultural HiJack: [Scholar’s Library]](http://astoryisnotatree.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/twitter-bg.gif)