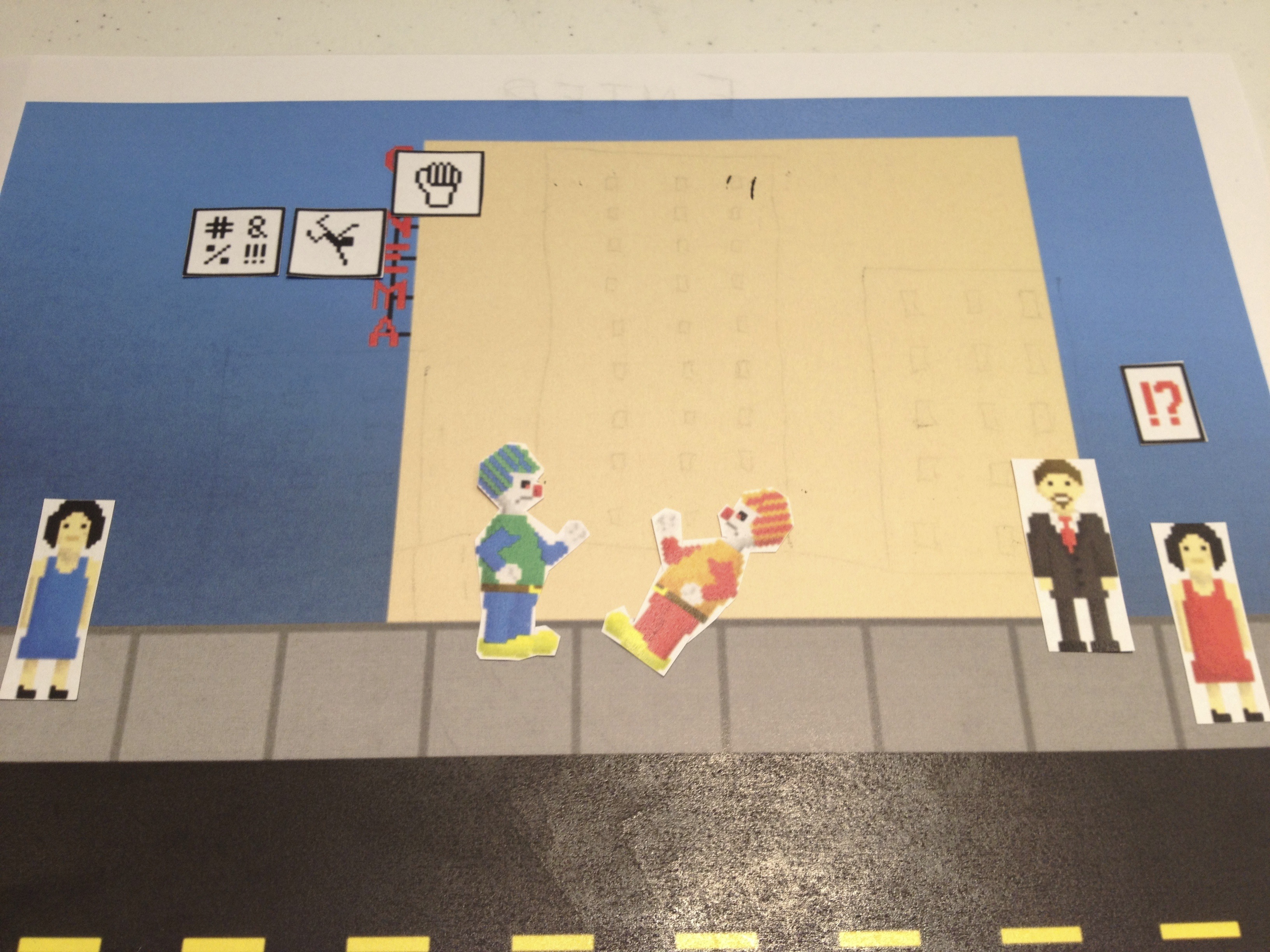

For my conference project I created a side-scrolling exploration/adventure game. The player controls an anthropomorphic hummingbird with a broken wing. The player progresses through the game by bartering with other anthropomorphic animals, providing them with items they need to repair damage throughout their dwellings. Along the way, the animals reward the player with mysterious parts, and at the end of the game the animals reward the player by building a hot-air balloon that will allow the player character to continue his migration.

The project did not change a great deal from conception to realization. The bartering mechanic was part of the game from the beginning, as was the general structure of the story and events. Decisions about what other animals to include in the game and what problems the player helps them with did change over time. I’d originally planned to include swallows in the game, but decided variety among the animals would be best. I opted for a bird, insects, amphibians, and mammals. Some animals in the game can fly, while others are terrestrial or amphibious.

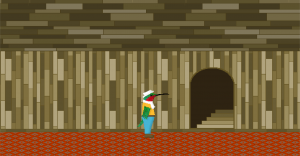

A lot went well during my work on this project. I’m quite pleased with most of the art and animations, although it’s imperfect. The player character was the first sprite I created for this project—before I had a clear sense of the aesthetics of the game—and the color palette doesn’t feel entirely at home with the rest of the art throughout the game. The tree interior and cave environments are most representative of the style I aimed for with this project, whereas the colors in the grass and pond environments are something I’d revisit.

I had no prior experience creating pixel art—and very little experience with visual art in general—but I’m pleasantly surprised by the results of my efforts. The game looks quite good. I also had zero programming experience and anticipated that programming this game would cause me a great deal of frustration and confusion. However, I found myself able to write all of the code this game required by adapting the basic concepts behind the Player Controller script presented in the GamesPlusJames 2D RPG tutorials on YouTube. I spent nearly two days writing my State Controller and Inventory Controller scripts and getting those to work, but generally I encountered few frustrating obstacles while programming this game.

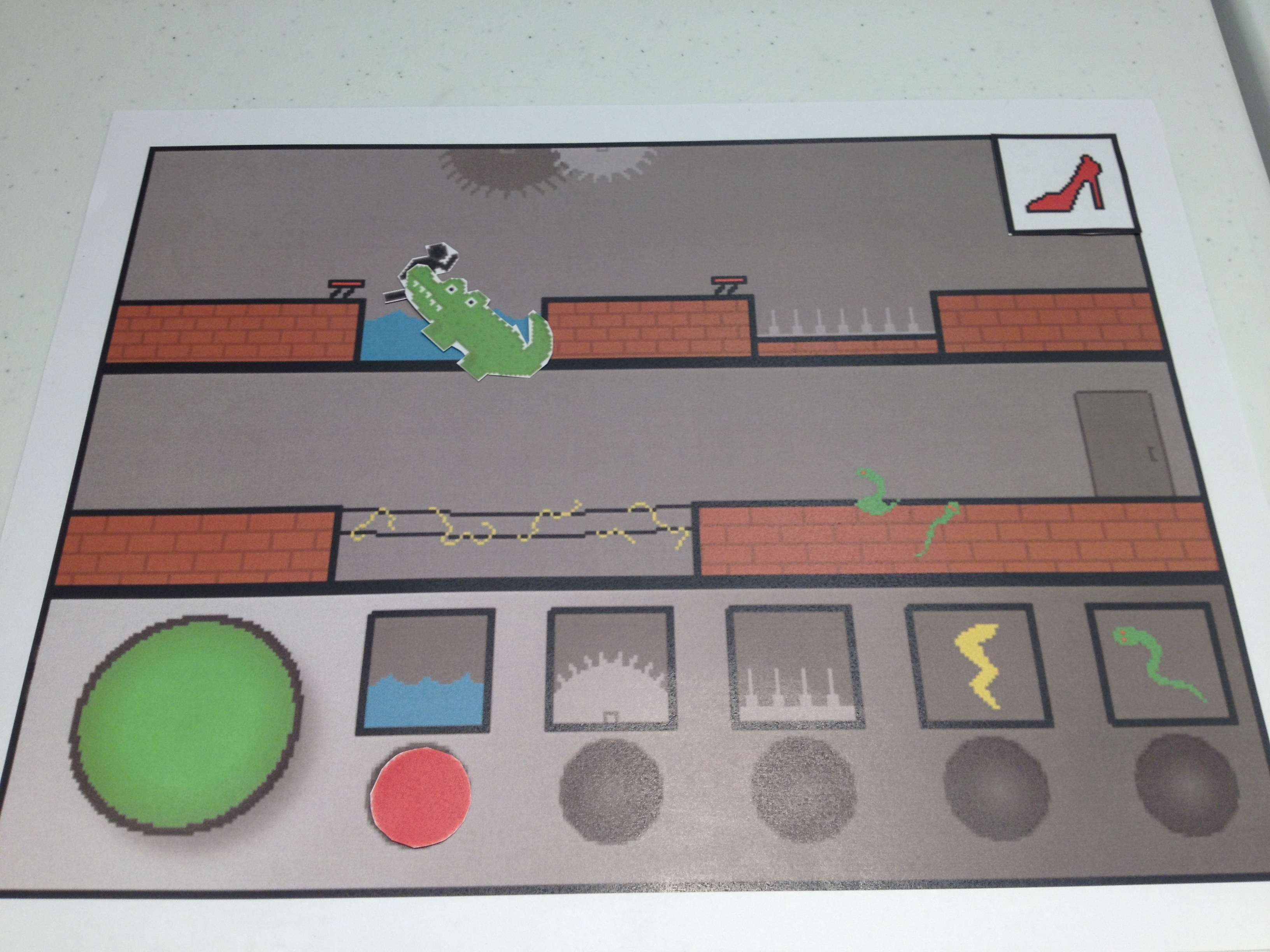

The animations required for this game were without a doubt the most difficult aspect of the process. The walk cycles for the player character required over eight hours of work, and the animation cycle for the water wheel required four-to-five hours.

I could have managed my time much better while working on this project. Finding sufficient time to work wasn’t the issue—I invested a great deal of time into this project—but the timeline of my work in no way correlated with the timeline laid out in the dev cycle. One major reason for this was the complexity of the art and animations. Early in the process of creating concept art and designing sprites, I decided to work in a resolution of 128×128 pixels. Rather than working with canvasses comprised of 1,024 or 4,096 pixels total, I worked with 16,384. In addition, the game includes some fairly complex animations. Both player walk cycles contain eight frames of animation (and because of shading and the broken wing creating the second walk cycle wasn’t as simple as x-axis reflection of images), and the water wheel animation is made up of eleven frames.

Because of the level of detail made possible by the higher resolution, creating the art and animations for my game consumed the vast majority of the time I dedicated to this project. I’d estimate that I spent ten hours on art and animations for every hours I spent coding. I knew early on that I’d have to deviate from the dev cycle because of my dedication to the visual aspect of the game, but even then I began coding in earnest far later than I’d planned. As a result, there’s still uncertainty about the state of completion my game will be in by the end of the semester.

The non-linearity of this project stems mostly from two techniques: defamiliarization and central trauma. I present common animals in anthropomorphic forms, and these animals exist in constructed dwellings, wear clothing, and have a barter system. The hummingbird player character has a broken wing, and he provides assistance to various other animals by helping them to repair broken objects in their homes. I develop the motif of breaking, of damage, throughout the game, and this motif reaches its resolution at the end of the game once the player character has helped the various animals fix their broken things and the animals have rewarded these acts of kindness by building a hot-air balloon.

I took some inspiration from Adam Cadre’s “Photopia,” specifically from how Cadre incorporates the non-linear technique of central trauma into his story. “Photopia” revolves around its central trauma without addressing it directly; instead, it sort of prods and catches glimpses of the trauma through a variation-on-a-theme repetition. The player or reader grows to understand the trauma through association and pattern recognition. I attempted to approach central trauma in a similar way in my own game.

I had numerous children’s books in the back of my mind while creating this game, and influences include the Frog and Toad books by Arnold Lobel and the animated film “The Wind In the Willows,” directed by Dave Unwin and based on the books by Kenneth Grahame.

Although I may not implement as many of these changes as I’d like before the end of the semester, I was encouraged by play-testing to include far more objects within the world that allow interaction. Play-testing also encouraged me to add reaction animations to the NPCs when the player interacts with them.

To create my maps, I used Tiled in combination with larger images inserted into the game directly through Unity as game objects. I used collision and key binds in order to support proximity-based interaction without the interactions triggering automatically. For example, I wanted the player to be able to walk past doors and NPCs without interacting if the player wished, so my code requires to player to collide with an NPC/object and use a command in order to interact. I came up with one solution that I’m particularly proud of to the problem of the sky. Although I first considered simply adding one large blue field behind the trees in the forest level, I knew I wanted a subtle gradient in the background. However, I also knew that the gradient would shift as the player moved along the map, so I created a gradient field of blue about the size of the camera’s field of view and added it to the game as a child of the player so that the gradient would move with the player and remain constant.

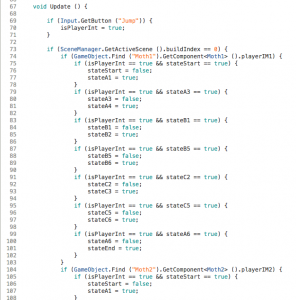

Coding the State Controller and Inventory Controller proved to be challenging. I created string of boolean logic comprised of nests-within-nests, activating and deactivating eighteen different variables in different orders based on the player’s actions. This caused me a great deal of headache, because the first two or three versions of these scripts failed to work as I’d intended. I felt confident in my logic, my nesting of if/then statements, and my organization of the eighteen bools, but pinpointing the exact cause of my code’s dysfunction took hours of thought and experimentation. I eventually identified the problem: my code was structured around the location of scripts attached to game objects throughout the world, however, when Unity fails to locate an object in the current scene, it ends its search rather than attempted to locate other references game objects. My solution to this was to restructure my State Controller script by nesting all of my game object searches within a lines of code that checked the current scene’s numeric identifier. Therefore, when the player occupies scene one, the State Controller script only searches for the game objects present in scene one, and none of the game objects present in scenes zero, two, and three.

Overall I found this project exciting, challenging, and highly educational. I may continue work on this project even if I don’t I plan to involve myself in game design projects in the future.